Something was clearly different as I approached the gate on a recent Saturday night at São Paulo-Guarulhos, Latin America’s busiest airport. Few passengers brandished the shirts with supersized logos of polo players commonly sighted at check-in to Miami and Lisbon. Instead, I was struck by the remarkable diversity of passengers, with a considerable number of Chinese, African and Arab travelers waiting to board. Two Brazilian honeymooners ahead of me in the line perused their Thailand travel guide, surrounded by animated chatter in Cantonese, Farsi and Amharic.

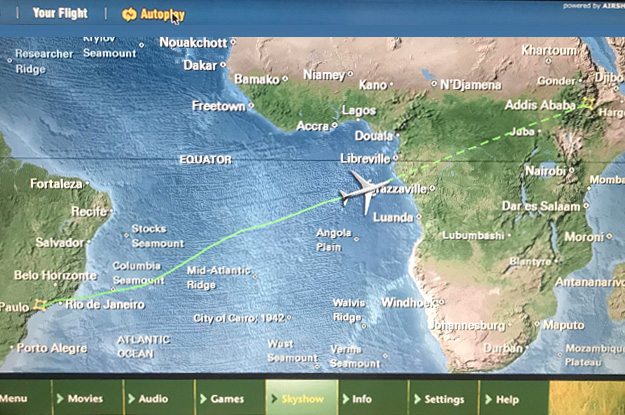

This 12-hour, non-stop Ethiopian Airlines flight to Addis Ababa speaks volumes about changing dynamics in the so-called Global South.

First of all, Ethiopia, Africa’s second most-populous country, has experienced the continent’s fastest economic growth over the past decade, despite having no oil or other strategic resources. At a time when Brazil’s image is badly tarnished by corruption scandals (chiefly Odebrecht) in the rest of Latin America, the importance of African markets will inevitably increase for globally-minded Brazilian companies in coming years.

Yet more importantly, Addis Ababa, home to the African Union and probably the continent’s safest metropolis, is now the best-connected African hub to China. It has daily connections to five Chinese cities, including Guangzhou, informally known as “the capital of the Global South” among migrants from developing countries all over the world.

At a time of a broad shift of economic power to Asia and China in particular, Brazil’s geographic distance (more than 10,000 miles from São Paulo to Beijing) remains a hurdle, making it harder for Brazilian businessmen, politicians, journalists and academics to frequently travel to and engage with the Middle Kingdom. Despite the fact that China became Brazil’s most important trading partner in 2009, Brazilian elites remain largely ignorant of China and Asia. Far too few Brazilians speak Chinese, and young students at Brazilian elite universities continue to prefer spending their exchange semester in Barcelona or Paris rather than Beijing or Shanghai. In the face of China’s growing influence in Latin America, the need to gain a better understanding of Beijing has never been greater.

The flight from São Paulo to Addis Ababa connection, which until recently included a refueling stop in Lomé, Togo and has been in operation since 2014, is helping build those bridges. Also waiting in line for the flight I took was a group of Brazilian teenagers wearing matching shirts for a Brazilian-Korean exchange program. Even here, though, there were misconceptions. One of the students confided that her parents “are really worried” because her flight was stopping over in Addis Ababa, instead of “a fancy place like Dubai.”

Ethiopian Airlines staff is unfazed by such comments. “When we started to offer the direct connection to Addis Ababa to Brazilian travel agencies, some asked if the airline served food on flights and whether the airline did regular technical maintenance of its aircraft,” Raphael de Lucca, the airline’s sales manager in Brazil, told me with a grin.

The irony is that, while established carriers often send their oldest aircraft to the region (a phenomenon Venezuelan political scientist Moises Naím once famously called the “American Airlines syndrome” symbolizing how little the United States cared about Latin America), Ethiopian Airlines is part of the technological vanguard, being the first airline to have introduced the Boeing 787-800 Dreamliner to the Brazilian market.

The time around the Chinese New Year, a date barely known to most Brazilians, is among the busiest periods of all. To better adapt to increasing Chinese demand, Ethiopian now provides Chinese staff on board, as well as Chinese food, on its connections to the Middle Kingdom. It is an example Brazilian hoteliers would be wise to follow. Chen, a Chinese businessman from Guangdong province explains to me in the airport lounge before taking off to Addis Ababa, finding decent Chinese food in Brazilian luxury hotels was so difficult that he simply brought his own.

These issues are being addressed, slowly. One day at a time. One flight at a time.