Photo Essay

Afro-Latin Religion

African and African-inspired religions in Latin America and the Caribbean are as diverse as the region itself. But as you will see in these pages, many of them share rituals, beliefs, language and even veneration of the same gods—revealing common origins in Western Africa. To celebrate the United Nations’ International Decade for People of African Descent, which began in 2015, AQ offers this visual panorama of African and African-inspired religions in our hemisphere.

jim richardson/national geographic/getty

A believer in the Vodou spirit Gede takes part in Day of the Dead celebrations in Port-au-Prince. Followers of Haitian Vodou, which draws on both Roman Catholic and African influences, mark the day by offering food, alcohol and candles to the spirits.

Brazil

Candomblé

Candomblé is a religion of divination, sacrifice, healing, music, dance and spirit possession that originated among Africans and Afro-Brazilians in 19th-century Bahia, in northeastern Brazil. Believers attribute miraculous powers to gods whose adventures, personalities and kinship make up an extensive body of oracular wisdom. Though believers were persecuted until recent decades, today some temples are actively sponsored by the state, and have been officially incorporated into national, state and municipal patrimonies.

mario tama/getty

During their ceremonies, practitioners of Candomblé fall into trances during which they are transformed into the gods, or Orixás, they worship. Here, followers stand during a Candomblé ceremony in Itaborai, Brazil.

raul spinasse/agencia a tarde/ap

Devotees make an offering of flowers to Iemanjá, a Candomblé goddess, during celebrations in Salvador, in northeastern Brazil. Iemanjá is considered the Queen of the Seas and the patron of Brazil’s fishermen.

haroldo abrantes/agência a tarde/ae/ap

A statue of Iemanjá in Rio de Janeiro. Many African-influenced religions, including Candomblé, venerate gods called Orixás, who have dominion over natural and social forces, such as lightning, rivers, love, war and wealth.

bruno domingos/reuters

Celebrations during St. Roch Day, a festival for the Roman Catholic saint equated with Omolú, the Candomblé god of skin diseases. Popcorn is used to cleanse people’s bodies of disease and other malign forces.

Venezuela

The Cult of María Lionza

Similar in many respects to Cuban Santería, the Cult of María Lionza incorporates elements of African, indigenous and Catholic customs and iconography. Adherents venerate María Lionza, a goddess born in the 1800s whom they call La Reina. The religion — the second most widely practiced in Venezuela — does not supplant Catholicism for most believers, but supplements it with additional rituals and beliefs.

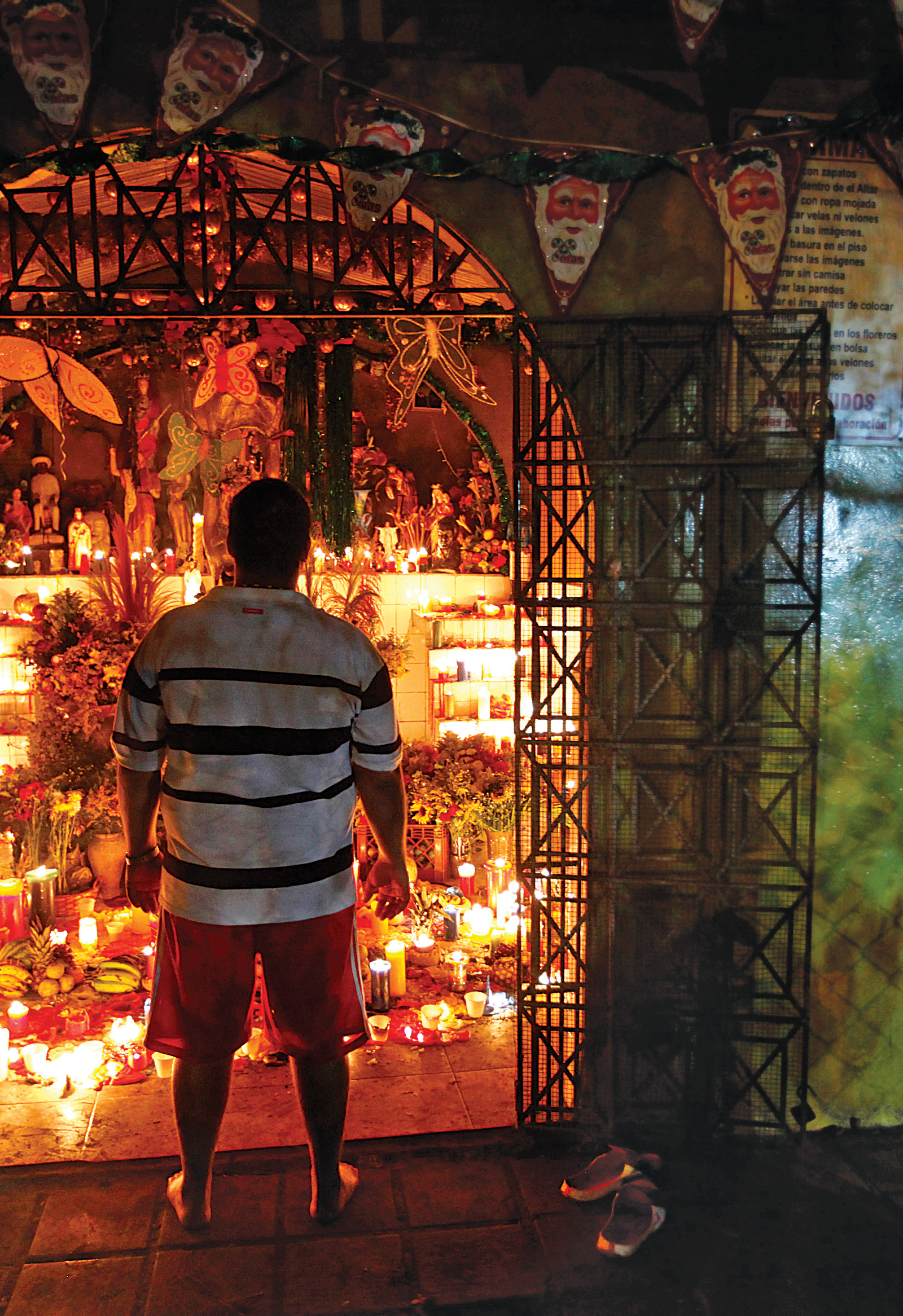

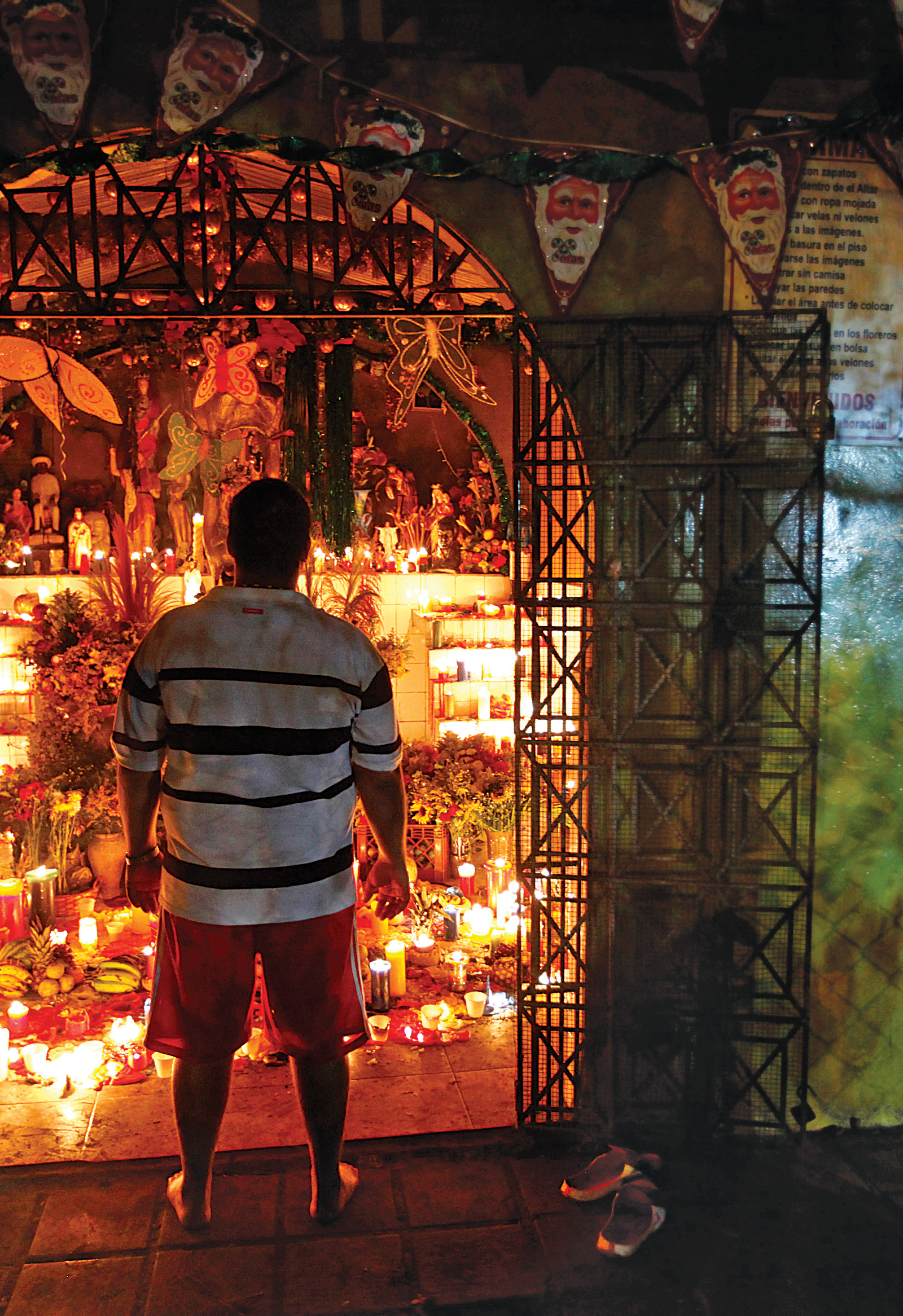

jorge silva/reuters

The annual religious festival of María Lionza brings tens of thousands of followers to chapels like this one in the mountains of Venezuela. Here, a man stands in front of a shrine to the goddess on the mountain of Sorte in Yaracuy.

ariana cubillos/ap

Followers of María Lionza believe the goddess was an indigenous woman born on Sorte mountian in Venezuela. Here, adherents participate in a ritual during an annual gathering to honor her.

marco bello/reuters

A follower of María Lionza smokes a cigar to honor the goddess, alongside members of Venezuela’s National Guard.

Haiti

Vodou

Haitian Vodou derives many elements from the practices of enslaved African people, as well as from the indigenous Taíno people of Hispaniola (modern day Haiti and the Dominican Republic). However, it is chiefly inspired by African religions and Roman Catholicism. Adherents identify Bondye as the world’s ultimate creator — a god so inconceivable to humanity that practitioners more directly serve spirits called Iwa, who act as intermediaries. Vodouists seek harmony with the spirits around them that determine their well-being.

hector retamal/afp/getty

Haitian Vodou followers bathe in a sacred pool during an annual festival held during Easter weekend in Souvenance, Haiti.

andres martinez casares/reuters;

A devotee prays at a cross consecrated to Baron Samedi, a Vodou spirit, on the outskirts of Port-au-Prince.

anastasia moloney/reuters

The late Max Beauvoir, once the supreme leader of Haitian Vodou, was a trained bio-chemist who founded the Temple of Yehwe, a nonprofit organization dedicated to promoting understanding of African and African-influenced religion in the Americas. He died in September 2015 at the age of 79.

Cuba

Santería

Cuban Santería has been profoundly influenced by Western African conceptions of personhood and the divine. The practice, which includes elements of spirit worship based on the rituals of the Yoruba ethnic group, first developed in communities of enslaved African people in the cities and on the sugar plantations of the island in the 19th century. Its influence has since spread throughout the Americas, especially since the Cuban revolution of 1959, when many Cubans, including Santeros, fled the island.

ramon espinosa/ap

In Cuba, the Catholic holiday celebrating Our Lady of Regla, an apparition of the Virgin Mary, falls on the same day as the celebration in honor of Yemayá. Here, a follower of the Santería religion in the town of Regla carries a doll that represents the sea goddess.

ramon espinosa/ap

Religious icons, including an Indian Spirit, the Virgin Mary and Buddhas, adorn the home of Santería followers in Havana, Cuba. A soup tureen in the shape of a blue fish embodies the sea goddess Yemayá.

ramon espinosa/ap

The feast day procession for the Virgin of the town of Regla. The apparition of the Virgin Mary in Regla is recognized by the Catholic Church, but is also associated with the Santería sea goddess Yemayá.

Dominican Republic

Vodou

The rituals and beliefs of the West African Vodun religion have influenced spiritual practice in many parts of the Americas. In Haiti, Cuba, Brazil, the United States and elsewhere, forms of the religion have been syncretized with Christianity and adapted according to local custom. In the Dominican Republic, Vodou (or Vudú) occupies an important but less defined role in spiritual life than it does in neighboring Haiti. While the two practices share common threads, the origins of many Dominican Vudú customs and beliefs are unique to the form of the religion practiced in the country.

ricardo rojas/reuters

People take part in a Gaga ceremony, a music and dance performance originating in Haiti and inspired by the Vodou religion.

ricardo rojas/reuters

Part of the Gaga ritual performance in the Dominican Republic. Gaga is a Vodou-inspired ceremony held during the Catholic Holy Week.

photofusion/universal images group/getty

Part of the Gaga ritual performance in the Dominican Republic. Gaga is a Vodou-inspired ceremony held during the Catholic Holy Week.

Jamaica

Rastafari

Formed during the 1930s in colonial Jamaica, Rastafari has since achieved global recognition thanks in part to the popularity of Bob Marley and Reggae music. Rastas adhere to and reinterpret parts of the Bible and believe in the divinity of Haile Selassie I (Ras Tafari), the late emperor of Ethiopia, who they believe represented God in the flesh. Inspired by their prophet, Marcus Garvey, and Pan-Africanism, they believe in returning to Africa spiritually and physically — particularly Ethiopia, which is considered holy land.

ricardo rojas/reuters; photofusion/universal images group/getty

Rastafari iconography incorporates Judeo-Christian and African symbols in messaging that deals with the African slave trade through parallels to Biblical stories of the exodus.

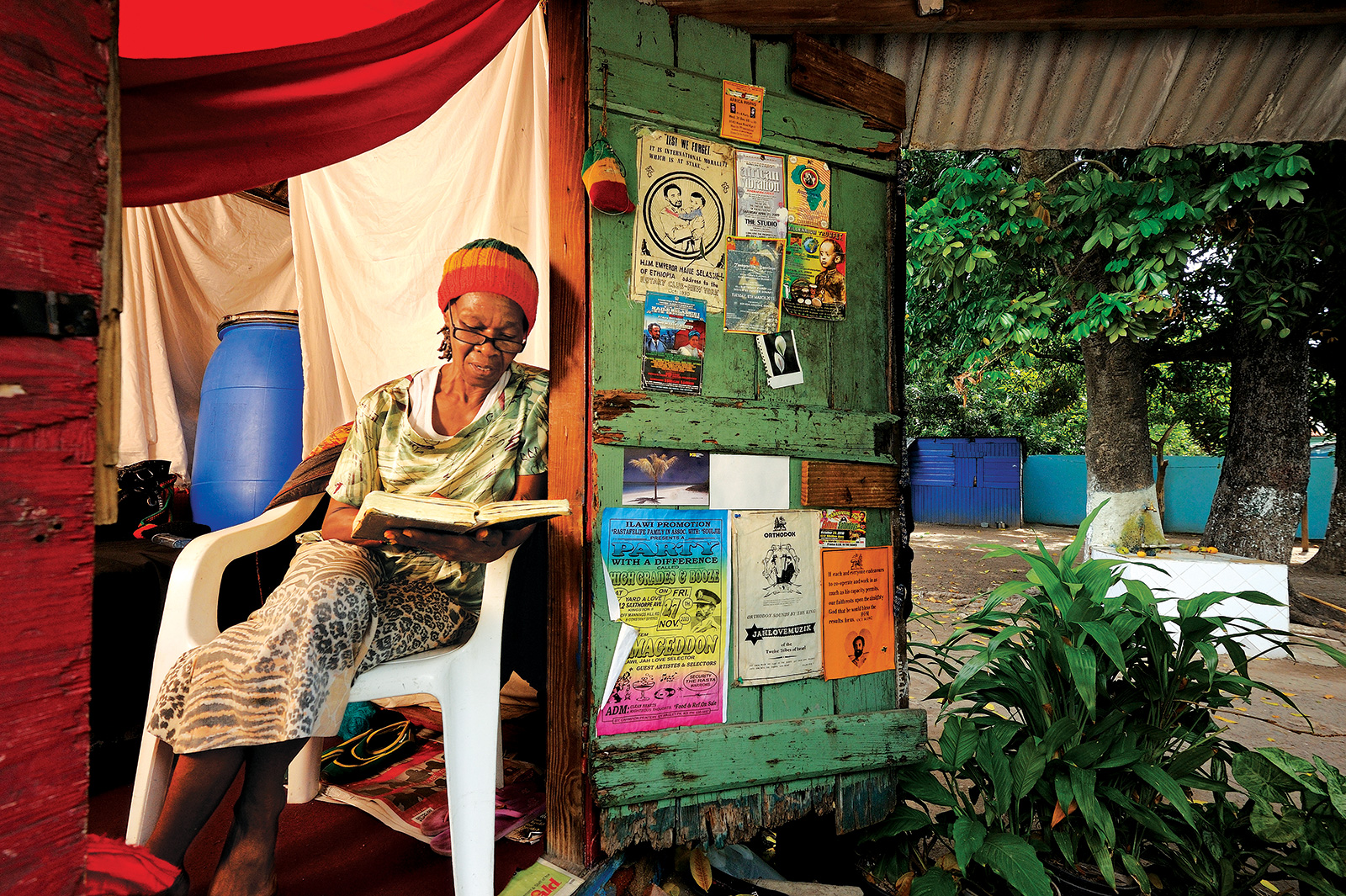

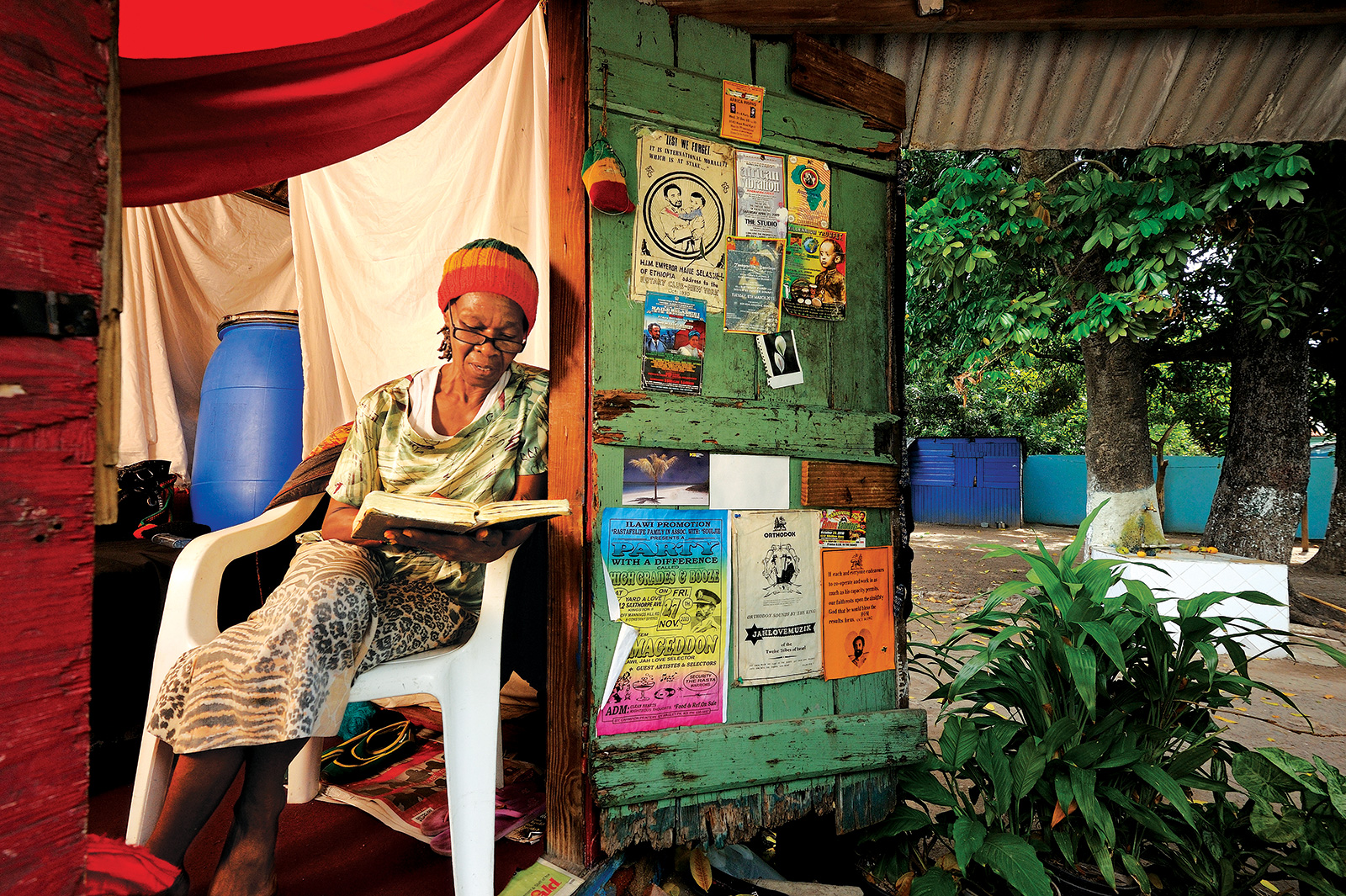

jim richardson/national geographic/getty

A Rastafari woman reads the King James Bible in the Jamaican capital of Kingston.

Portions of the captions and introductory text in this essay have been adapted from the book Black Atlantic Religion (2005) by Dr. Lorand Matory, in consultation with the author. Additional consultation provided by Dr. Ivor Miller.