When the Cuban Revolution celebrated its 50th anniversary in early 2009, Raúl Castro boasted it would be around for another 50 years. Change, however, is in the air.

For one thing, Fidel Castro, though still audible from the sidelines through his reflexiones, is in the twilight of his reign. His brother Raúl, now ascended to the presidency, has implemented some timid economic reforms and sounds like a blend of Max Weber, Henry Ford and Vladimir Lenin with his continuous references to institutionalization, efficiency and productivity. Since taking power in February 2008, the younger Castro (by five years) has replaced more than a dozen ministers and placed key military allies in prominent positions.

To some, this reflects a normal process of consolidation, and even rationalization of power. But to others, the personnel changes—not least the defenestration of Vice President Carlos Lage, Foreign Affairs Minister Felipe Pérez Roque and Secretary of the Communist Party Central Committee Fernando Ramírez in March 2009, after they were taped at a dinner party poking fun at the elder Castro and criticizing his successor—have “generational” conflict and frustration written all over them.

Equally significant is a more “silent” transition, underway over the past 20 years. This has been marked by the reintroduction of capitalism, growing social stratification and inequality, an incipient civil society, and by the weakening of a state whose capacity to provide education, health and housing are in visible decline. According to official statistics from this year, there is a shortage of 600,000 housing units, a number that does not take into account the 440,000 homes damaged by devastating hurricanes last year.

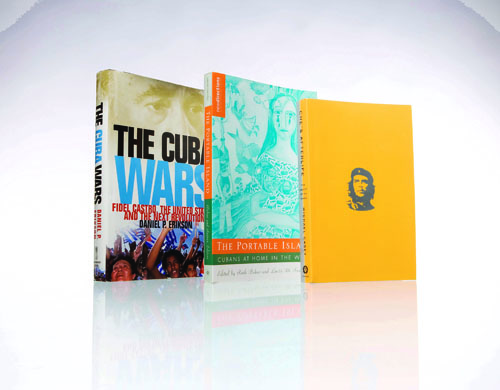

Three new books about Cuba do not explicitly offer predictions, but they do provide valuable background and clues as to what the future may hold for an island with a disproportionate presence on world politics. Two of the books—The Cuba Wars: Fidel Castro, the United States, and the Next Revolution and The Portable Island: Cubans at Home in the World—provide important insight into the Cuban imbroglio and the tremendous price Cubans have paid for the failure of democracy to take root. The third, Che’s Afterlife: The Legacy of an Image, shows another side of the Cuban global reach: the branding of the revolution.

The Cuba Wars, written by Daniel P. Erikson, senior associate at the Inter-American Dialogue and a long-time Cuba-watcher, is an intelligent, balanced and informative book with many good interviews and vignettes. Both general and specialist readers can learn much from it. To start with, the title is absolutely on the mark: the “cold war” between Cuba and the United States has outlasted the Cold War by 20 years; the “civil war” between Cubans on and off the island is now more than 50 years old; and for nearly five decades Fidel Castro and the regime have implemented a vision of politics as war by other means.

The Cuba Wars thoroughly and perceptively analyzes the events of the past 20 years, examining both the evolution of U.S. policy toward Cuba and the implementation of the regime’s “survival” strategy. That provides an opportunity for Erikson to explore some of the more intriguing stories in the Cuban-American standoff. He looks at the Wasp Network—a group of five Cuban intelligence officers who were convicted by a Miami jury in 2001—and the case of accused spy and former U.S. Defense Intelligence Agency senior analyst Ana Belén Montes. Both cases—and the more recent arrest (June 2009) of former U.S. State Department employee Kendall Myers and his wife on similar charges—underscore the effectiveness of Cuban intelligence. Erikson also looks at the internecine battles of the Cuban-American community, the judicial embarrassment surrounding the case of anti-Castro terrorist Luis Posada Carriles and Fidel Castro’s artful use of six-year-old Elián González. More topically, he covers the brutal crackdown on dissidents in 2003 and the emergence of Venezuelan President Hugo Chávez as the revolution’s new sugar daddy, providing more than 115,000 barrels of oil per day at subsidized prices.

Erikson, who conducted extensive interviews for the book (mostly outside Cuba), lets his subjects speak for themselves. And, occasionally, their words speak volumes. We hear the echoes of the ongoing debate within the Cuban government: economist Pedro Monreal, who later left Cuba to work in Jamaica, says lifting the embargo “would have a huge, rapid impact…[for which] Cuba would not be prepared,” but then observes that “many of my friends tell me that Cuba has the manpower to control the effects of lifting the embargo.”

The last chapter focuses on the country’s so-called “bridge generation,” born in the late 1960s and early 1970s and educated under the Revolution. There, Erikson correctly argues that Raúl Castro’s greatest challenge is in dealing with “the growing impatience of the island’s restless youth,” who are resentful of the bureaucratic hurdles to secure exit visas, the dual currency system that discriminates between those with and without access to dollars, and the limitations on travel within and off the island. Apathetic and pessimistic about the future, this younger generation, given a chance, will vote with its feet and leave the country.

Those who do leave Cuba join a diaspora that stretches from Miami to Moscow. This is the subject of The Portable Island, a book edited by University of Michigan anthropology professor Ruth Behar and Amherst College associate Spanish professor Lucía M. Suárez, which encourages the reader to reflect on how history has shaped Cuban identity. Cuba is a “portable island” not only for those who have left, but “even for [the Cubans] who live [there], for they are witnesses to the endless departures and returns, and they know what fits and doesn’t fit in a suitcase.” This extraordinarily rich book shines a light on what it means to be a member of the Cuban “tribe.” Contributors reside in and out of Cuba and some are even “between” Cuba and some indeterminate place, with each offering a window into the Cuban experience.

There is much to choose from in this book—essays, reflections, poetry, and drawings. My favorites are three essays that together provide a comprehensive look at little-known nuances about the Cuban people. For example, in “From Havana to Mexico City: Generation, Diaspora, and Borderland,” Rafael Rojas of the Centro de Investigación y Docenia Económicas in Mexico City explores the intellectually vibrant “transnational” Cuban community in the Mexican capital. Alan West-Durán, a Cuban Santero—or, follower of the Afro-Cuban religion known as Santería—shares an inside glimpse of

The ironic consequence of this failure to develop an independent and viable national project is the hyperbolic sensibility epitomized by the tirelessly iterated slogan socialismo o muerte (socialism or death).

This slogan, like many things Cuban, is often associated with the infamous image of Ernesto (Che) Guevara. Che’s life has been rigorously chronicled, but Michael Casey, the Buenos Aires correspondent for The Wall Street Journal, offers a different twist. Che’s Afterlife is the biography of a brand, and it tells the compelling story of how globalization, marketing and revolutionary politics combined to turn an image abstracted from a March 1960 photograph of Che taken by Fidel Castro’s personal photographer, Alberto Díaz Gutiérrez (known as Korda), into an icon that has transcended the “reality” of its subject. In the decades after Che’s death, the icon found new life as a Ben and Jerry’s ice cream flavor (Cherry Guevara), on a bikini worn by model Giselle Bündchen and most irreverently and ironically on a Coca-Cola ad sponsoring a Che memorial event on the 40th anniversary of his death.

As Korda’s photograph morphed into a generational icon, it infiltrated popular culture via Paris, Rome and New York, later returning to Latin America where it would become a fixture on t-shirts and at demonstrations. With the mid-1990s came a new marketing opportunity. The success of Che’s book The Motorcycle Diaries: Notes on a Latin American Journey and of the Che-inspired Revolución watches made by Swatch had hinted at “new opportunities to exploit the brand.” But in all of these cases

“…what was on offer was the idea of revolutionary nostalgia, not the fact of socialist reality.” Che would not have recognized the Cuba to which he had returned: “The growing disparities between rich and poor, the pervasive dishonesty, and the obsessive hunt for foreign currency [were] the antithesis of [his] utopian vision.”

In a final irony, the author notes that capitalism offered “the means of production and the distribution channels” to get the image of the iconic revolutionary to consumers. But the Korda image also needed a marketer-in-chief, a visionary who understood that his revolutionary religion needed both a myth and a saint. That man was Fidel Castro.

To cap his exploration into Che mythmaking, Casey finds an illegitimate son of Guevara named Omar Pérez López. Pérez, the child of a union between Che and Lilia López (then a University of Havana student), spent a year in one of the agricultural re-education camps designed by his father. His crime was to have signed the Third Option manifesto in the early 1990s which, in Casey’s words, “offered a minimal program of political liberalization that respected the socialist foundations of the Cuban revolution.” Pérez, 42 years old when he met Casey in 2006, is now a Buddhist monk. Asked why his father had left Cuba in the mid-1960s, the son responded: “He was running away.”

Change is on the way. This catchy slogan also applies to Cuba, but accompanying this inevitability is the certainty of its own melodic and unpredictable rhythm. Change will come, but on Cuban time and with those who live in Cuba as protagonists. All three books under review here provide important clues about the people and the politics of this magical island. Unfortunately, they also confirm the wisdom of now-retired Archbishop Pedro Meurice of Santiago de Cuba who once emphasized the ”anthropological lesion” its people had suffered. Such wounds are not easily healed, and they promise to make the Cuban transition a long and complicated process.