From 1931-1932, Mexican muralist Diego Rivera created eight large-scale, “portable” murals for a solo exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA). Eighty years later, five of these works—freestanding murals as large as six by eight feet, made of steel armature, reinforced concrete and frescoed plaster— have been reunited in “Diego Rivera: Murals for the Museum of Modern Art,” on view at MoMA through May 14.

Visiting on a recent Sunday, I was struck by how contemporary the themes of the works—which are divided into a Mexico and a New York series—felt. They span questions of national identity, class inequality and the role of public art in an increasingly commercialized art world.

The first half of the exhibition, dedicated to the Mexico-themed works, offers a somewhat mythologized chronology of Mexican history, from its pre-Columbian and conquista past to its revolution and then its industrial present. Though painted in New York in the six weeks leading up to the exhibition’s opening, they reflect themes Rivera explored in fixed murals he painted in Mexico during the 1920s, when the country was still emerging from revolution and was in the process of actively forging a new cultural identity. They were all produced in the classical fresco style, which Rivera studied in Italy in 1921 at the request of Mexico’s Minister of Education as part of a public art initiative by the Álvaro Obregón government.

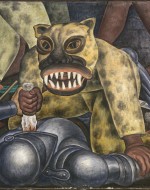

In one mural, Indian Warrior (1931), the viewer’s eyes are met by those of an Aztec warrior clad in a jaguar mask and skin, triumphantly stabbing an armored conquistador in the throat. For the ancient Aztecs, the jaguar symbolized power, and they believed wearing its mask or skin could impart superhuman abilities. Though the outcome of the Spanish conquest is well known, in showing the Aztec warrior as triumphant, Rivera here inverted the historical power relationship to elevate Mexico’s pre-Columbian roots.

In one mural, Indian Warrior (1931), the viewer’s eyes are met by those of an Aztec warrior clad in a jaguar mask and skin, triumphantly stabbing an armored conquistador in the throat. For the ancient Aztecs, the jaguar symbolized power, and they believed wearing its mask or skin could impart superhuman abilities. Though the outcome of the Spanish conquest is well known, in showing the Aztec warrior as triumphant, Rivera here inverted the historical power relationship to elevate Mexico’s pre-Columbian roots.

In the two other Mexico paintings on view, Rivera again purposefully combined fact and fiction. Agrarian Leader Zapata (1931) shows Emiliano Zapata, a key figure in the Mexican Revolution and leader of the agrarian reform movement, as he stands over the dead body of an opponent, wearing the simple cotton clothing and sandals typical of peasants rather than the elaborate outfits for which he was typically known. In changing this simple detail, Rivera identified Zapata even more closely with the masses of peasants, helping to solidify his status as a hero and further craft a narrative shared by all Mexicans.

In Rivera’s New York-themed works, added after the exhibition opened, the artist explores the contradictions between labor, industry and wealth. While some see this as a direct outgrowth of his affiliation with Communism, the reality is more nuanced. Rivera, who officially joined the Communists in 1921, had a rocky relationship with the party and was expelled from it in 1929. Moreover, while he celebrated the dignity of labor, Rivera was also clearly excited about industrialization and the achievements it generated; he once called laborers “the catalysts that transform the raw materials of the earth into energy” and admired the U.S. for being “a truly industrial country” in contrast to Mexico.

For example, in Electric Power Plant (1931-2), Rivera depicts the interior of a power plant beneath an outline of New York City in the background. He appropriates the streamlined, metal images of machinery but also places individual workers at the heart of his painting. I was particularly moved by a separate series of sketches rendered mostly in red, orange and black shades that show buildings in different phases of construction but focus consistently on the individual worker—at a precarious height, in active motion and powerful even against the backdrop of monumental buildings.

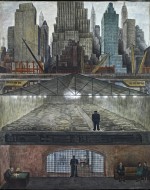

In Frozen Assets (1931-2), an ambitious three-tiered work, Rivera combines a sense of awe at New York City’s rapidly growing skyline with an unflinching depiction of class inequality at the height of the Great Depression. The top tier combines a number of famous skyscrapers into one view, including the Irving Trust Building, Bank of Manhattan Company Building, Rockefeller Center, and of course the Empire State and Chrysler buildings. Construction is ongoing, manifested through the inclusion of giant cranes and an elevated subway platform. In the next tier, a guard watches over hundreds of bodies sleeping in a steel-and-glass structure—presumably the Municipal Pier at E. 25th Street, a shelter for the unemployed (who comprised nearly 25 percent of the U.S.’s adult population at the time). In the bottom third, a security guard stands at the front of a bank vault while a woman examines the jewelry in her safe deposit box; an elegantly dressed man resembling John D. Rockefeller, Jr., and two women wait their turn.

In Frozen Assets (1931-2), an ambitious three-tiered work, Rivera combines a sense of awe at New York City’s rapidly growing skyline with an unflinching depiction of class inequality at the height of the Great Depression. The top tier combines a number of famous skyscrapers into one view, including the Irving Trust Building, Bank of Manhattan Company Building, Rockefeller Center, and of course the Empire State and Chrysler buildings. Construction is ongoing, manifested through the inclusion of giant cranes and an elevated subway platform. In the next tier, a guard watches over hundreds of bodies sleeping in a steel-and-glass structure—presumably the Municipal Pier at E. 25th Street, a shelter for the unemployed (who comprised nearly 25 percent of the U.S.’s adult population at the time). In the bottom third, a security guard stands at the front of a bank vault while a woman examines the jewelry in her safe deposit box; an elegantly dressed man resembling John D. Rockefeller, Jr., and two women wait their turn.

Today it’s impossible not to view these works in the context of the economic recession, the Occupy Wall Street movement and the sense that what it means to be “American” is rapidly changing in an increasingly globalized environment. The exhibition, “Diego Rivera: Murals for the Museum of Modern Art,” reminds us of the power of public art, whether to craft a shared narrative or to critique a given society’s mores. At a time when many countries are grappling with how to reconcile their individual histories with globally integrated economies and people are searching for collective and public outlets to express their discontent and frustrations, “Murals” is a reminder that public art still has a role to play.

*Nina Agrawal is associate editor of Americas Quarterly and policy associate at Americas Society and Council of the Americas.

**All photos courtesy of MoMA.