Brazil’s former Attorney General and Lava Jato veteran Rodrigo Janot likes to say that “Latin America used to be famous for its generals; now it is known for its prosecutors and judges.” Events over the last couple of months in places like Peru, Colombia and Guatemala are proving that Janot’s axiom still holds true.

Since 2015, anti-corruption protests have popped up almost everywhere in the region, converting law enforcement and judicial leaders into national celebrities. And there are no signs that social pressure is petering out. According to a recent Transparency International poll, 70 percent of Latin Americans believe ordinary people play a key role in the advancement of the fight against corruption.

Yet the street protests of late 2018 and early 2019 show that the new great power of prosecutors and judges comes with unprecedented scrutiny – and potentially strong opposition and social polarization.

In this sense, recent demonstrations in Peru, Colombia and Guatemala may be pointing to a deeper regional trend. In the first wave of anti-corruption protests in Latin America – in places like Brazil in 2015, at the beginning of Lava Jato, or Mexico in 2016, when a series of corruption scandals engulfed the Enrique Peña Nieto administration – citizens went to the streets in an against-everything-that-is-out-there mode. Enraged by their countries’ endemic corruption, they declared war on the political establishment with an all-encompassing agenda and a hazy view of what should be accomplished. These rebellions had direct electoral consequences, propelling anti-system figures such as Jair Bolsonaro in Brazil, Andrés Manuel López Obrador (AMLO) in Mexico or even Gustavo Petro in Colombia.

The mobilizations of the past few months look very different. These “anti-corruption 2.0” protests have been more targeted and less anti-establishment. Rather than ejecting a government or imploding the entire political system, the focus now is more likely to be on tangible obstacles to anti-corruption efforts.

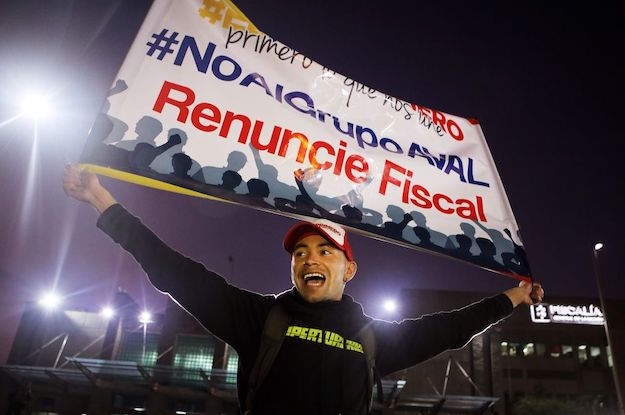

In Peru and Colombia, protesters took aim specifically at sitting attorney generals accused of stymieing Odebrecht probes in their respective countries. Peru’s Pedro Chávarry was pushed out of office after unsuccessfully trying, on New Year’s Eve, to remove two leading prosecutors in the case. Colombia’s Néstor Humberto Martínez – who as a former top lawyer for an Odebrecht partner had received information about the bribing of politicians since at least 2015, according to leaked audio – has managed to survive due to strong support from Senator Álvaro Uribe and less attention from the media since the Jan. 18 ELN terrorist attack. But public suspicion has not subsided and in the last couple of weeks his office was again surrounded by protesters.

The situation in Guatemala with CICIG is different, but elements of the 2.0 transformation are certainly present. President Jimmy Morales’ decision to expel the UN-backed investigative body on Jan. 7 sparked a new wave of demonstrations thrusting Colombian-born CICIG Commissioner Iván Velásquez to the center of attention. On the streets, most protesters hailed him as a hero while others denounced Velásquez as the leader of a foreign intervention. Protests were mostly about him and Morales, rather than the entire political establishment as in the case of demonstrations in 2015.

Different factors are driving this transformation in social mobilization. One is education: After several years with corruption at the top of the national agenda, citizens know more about the issue, journalists are better at covering it, civil society is more experienced in its response and compliance has become a priority for serious private sector leaders. Also, even slight improvements in the economic scenario in countries like Brazil and the emergence of new faces in presidential offices and parliaments across the region has calmed the anti-establishment rhetoric – at least for now.

Looking ahead, this evolution could lead to political outcomes that are also very different from what Latin America has experienced in the past couple of years. If the anti-establishment impulse ceases to be a catalyzing element, the appeal of outsiders and new political leaders might also diminish. Also, the heightened scrutiny of law enforcement, judges, government officials and lawmakers could increase the costs of behind the scenes maneuvers against anti-corruption investigations and policies.

Even in Brazil and Mexico, where protestors have been silent in the last few months, there are reasons to believe that the 2.0 transformation is already underway. With Bolsonaro and AMLO in office, anti-establishment rhetoric is losing traction and the anti-corruption discussion is becoming more specific. Some high-profile cases could spark a fire: for instance, a move by Brazilian authorities to shelve money laundering investigations involving Senator Flávio Bolsonaro, the president’s son, or any sign that AMLO’s new attorney general, Alejandro Gertz Manero, is behaving as a so-called fiscal carnal to protect the government, could get Brazilians and Mexicans back on the streets.

In the end, the anti-corruption protests 2.0 trend could be a modest but encouraging sign of political maturity. Greater scrutiny of public officials involved in combating graft, coupled with less anti-system rage will be good for Latin American democracies. However, its limits are clear. While public opinion still tends to “personify” the fight against corruption, international experience and academic literature strongly indicate that long-term improvements hinge on institutional reforms, and therein lies the risk.

Citizen pressure has been key to propel the anti-corruption movement and Latin Americans may be ready to massively demonstrate against an attorney general or a piece of legislation suspected of undermining an investigation. To get people to the streets to tweak rules imposing stricter rules to select the attorney general in the first place? That is a much harder sell.

—

Simon is the politics editor for AQ and the senior director for policy at AS/COA