This article is adapted from AQ’s special issue on the U.S.-Mexico relationship. To receive AQ at home, subscribe here.

Those looking for affirmation of President Donald Trump’s “bad hombres” idea of the border are more likely to find it in fiction than in fact. Through much of its history, Hollywood has portrayed U.S.-Mexico relations through a lens of antagonism, or painted northern Mexico as a lawless land of bandits and corruption. Westerns such as John Wayne’s The Alamo (1960), Orson Welles’ classic noir Touch of Evil (1958), or Sam Peckinpah’s violent road movie Bring Me the Head of Alfredo Garcia (1974) are prime examples.

Mexican cinema itself has gotten in on the act, appropriating the theme of illegal migration through exploitation genres such as the “wetback” and “trucker” films of the 1970s and 1980s. Well-known Mexican directors have since offered more sympathetic treatments of migrants, as in Alejandro González Iñárritu’s Babel (2006), Diego Quemada Diez’s La Jaula de Oro (2013), and Jonas Cuarón’s Desierto (2015). These films have their merits, but they continue to describe the binational relationship primarily as one of conflict.

However there are some recent films and TV series that address the complexity of border relationships without papering over the sometimes violent juxtapositions that surround them. Here are three recent productions that, in vastly different ways, succeed in illuminating those relationships and, rather than reinforce Trump’s view of U.S. self-sufficiency, provide an antidote to it.

Traffic The progenitor of modern border storytelling in Hollywood is Steven Soderbergh’s Traffic (2000). Shot in a semidocumentary style, with intersecting narratives and a unique aesthetic, Traffic was visually innovative for its time, but also took narrative risks. For the first time in popular cinema, the film offered a portrayal of the drug trafficking problem in which the U.S. was not just a participant, but a codefendant.

The progenitor of modern border storytelling in Hollywood is Steven Soderbergh’s Traffic (2000). Shot in a semidocumentary style, with intersecting narratives and a unique aesthetic, Traffic was visually innovative for its time, but also took narrative risks. For the first time in popular cinema, the film offered a portrayal of the drug trafficking problem in which the U.S. was not just a participant, but a codefendant.

Two storylines in Traffic feature Americans living comfortably without knowing—or without caring to know—that their families are part of this dynamic: a newly appointed White House drug czar (Michael Douglas) who discovers that his daughter has a problem with addiction; and a rich housewife (Catherine Zeta Jones) who has ignored her husband’s dealings with a Mexican cartel.

Traffic debuted six years before Mexico’s then-President Felipe Calderón declared his war on narcotráfico, unleashing a wave of violence in the country that continues to this day. But while the film didn’t anticipate this new reality, its primary reflection remains relevant: The drug business in Mexico is a product of demand for narcotics in the U.S. and the money laundering that keeps it lubricated.

Another subplot of the film, involving a police officer in Tijuana (Benicio del Toro) who accepts a job with a military man allied with the cartels, exposes the equally painful truth that the salary and protections the Mexican government offers its police are not enough to liberate them from the temptation to switch sides.

The contrasts that Traffic draws between the judicial and economic systems of Mexico and the U.S. are stark, but the film’s most telling point is the suggestion that the drug trade is nourished by inequalities between border communities. The inverse implication—that better living conditions can reduce drug violence and criminality—is what Traffic aims to capture in its final scene. After collaborating with the U.S. Drug Enforcement Agency, Del Toro’s character asks that they install an illuminated youth baseball field back in Tijuana. The message is clear: Investments like these would be much more effective in improving lives on both sides of the border than, say, building a wall.

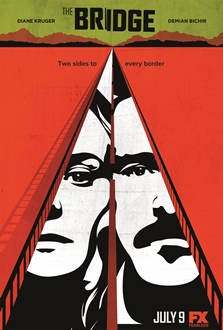

The Bridge Adapted from the Swedish-Danish TV series Broen/Bron, the short-lived FX series The Bridge (2013) took themes from the Soderbergh film a step further. The first episode takes place on the Bridge of the Americas, an auto crossing between Juárez and El Paso. A blackout has left the bridge in darkness, and when the lights come back on, police discover what they believe to be one dead body. It turns out to be two: the torso, belonging to an American judge, lies on the Texas side of the line; the legs of a young, unidentified Mexican woman lie on the other. This grisly discovery obliges detectives from both sides of the border to solve the case together.

Adapted from the Swedish-Danish TV series Broen/Bron, the short-lived FX series The Bridge (2013) took themes from the Soderbergh film a step further. The first episode takes place on the Bridge of the Americas, an auto crossing between Juárez and El Paso. A blackout has left the bridge in darkness, and when the lights come back on, police discover what they believe to be one dead body. It turns out to be two: the torso, belonging to an American judge, lies on the Texas side of the line; the legs of a young, unidentified Mexican woman lie on the other. This grisly discovery obliges detectives from both sides of the border to solve the case together.

But while the opening imagery is unsettling, the idea of a human hybrid—half Mexican, half American—is an apt metaphor for the dual character of the borderlands. The Bridge effectively uses this dynamic to introduce an angle that was absent in the Soderbergh film: The shared identities of border residents can put them in deadly conflict, but they lead to friendship and affection, in addition to mutual dependence.

That duality is illustrated by the complex relationship between the show’s central characters. Mexican state police officer Marco Ruiz (Demián Bichir) and the American Sonya Cross (Diane Kruger), the two agents tasked with solving the crime together, are destined to clash. Marco is impulsive and disordered; Sonya is meticulous and cold. Marco’s nonchalant nature allows him to navigate the turbid waters of Mexican policing; Sonya’s brusque impassivity, and the suggestion she has Asperger’s, is a clinical metaphor for the unemotional and precise character often attributed to officials in the United States.

Yet the series soon introduces characters who turn these national stereotypes upside down. Detective Ruiz’s impulsivity is reflected in the gringo journalist Daniel Frye, an impetuous addict with a dark past. And there are echoes of agent Cross in Adriana Méndez, the hardnosed Mexican journalist whom Frye takes under his wing. Frye and Méndez join forces to investigate the case themselves, representing the mirror image of the pair of detectives. Indeed, each character in The Bridge has a replica on the other side of the border, and government agents from both countries prove themselves complicit in the horrors of the drug war, continuing the discussion of shared responsibility that Traffic put on the table.

Sicario

Like The Bridge, Denis Villeneuve’s Sicario (2015) also begins with a grisly scene on the border. An FBI team led by Kate Macer (Emily Blunt) is preparing to raid a suburban home occupied by cartel gunmen. The raid quickly devolves into an exchange of heavy gunfire, and when the smoke clears, a hole in the drywall reveals a macabre surprise: The spaces between the tract-home’s flimsy walls are stuffed with unidentified bodies wrapped in plastic.

As the opening scene suggests, Sicario paints a bleak picture of the U.S. -Mexico border. In just the first six minutes of screen time, Villenueve renders true the worst fears of many Americans, with faceless Mexicans infiltrating the country as part of a vast criminal network, leaving violence in their wake. The cadavers stuffed into the walls could belong to rival gang members or to illegal immigrants — either way, they are evidence that those “bad hombres” operate beyond the scope of normal morality.

Benicio del Toro interrogates Mexican migrants in a scene from Sicario

Benicio del Toro interrogates Mexican migrants in a scene from Sicario

Such a depiction can appear to have given in to sensationalism, but really the difference between this film and The Bridge or Traffic is that Villeneuve offers a less empathetic view of his characters and the situations they face. The French-Canadian Villeneuve’s work is characterized by moral ambiguity, and Sicario is no exception. In a drug trade that is often portrayed as a conflict between good and evil, neither side can claim absolute moral superiority.

Sicario lays bare ugly truths about the drug war that can be uncomfortable to accept. Villeneuve’s idealistic U.S. protagonist finds that the struggle against the cartels is not always ethical, transparent or legal. As her eyes are opened to the perverse complexities of the war on drugs, Kate sees the degree to which her own government is willing to compromise its values.

Shortly after Sicario debuted, a city councilman from El Paso convened a panel of journalists and academics to discuss its grim portrayal of the border. Juárez had long been considered one of the most dangerous places on Earth, but at the time of the film’s release, the city was enjoying a steep drop in violence and a revival of cultural and civic life. Most panelists thought Villeneuve’s film painted an unfair picture of the new Juárez. But one saw value in the pessimistic view of border life. The director of an organization that helps migrants who have been the victim of crimes said that the film “serves as a reminder to people that things still aren’t okay in Juárez.”

This idea underlines the challenge of depicting the border on screen. It is true that Juárez, Tijuana, and other northern cities are not “okay” — rising murder rates in 2016 make that plain. But neither is the border a one-dimensional place. Manichean portrayals of the U.S.-Mexico divide — in fiction or in real life — do little justice to the lives that are lived on and across it.

As never before, the U.S.-Mexico border is now the subject of media attention and curiosity the world over, owing to the real and symbolic implications of Trump’s plans to extend the wall that separates the two countries. But while the U.S.-Mexico border divides two places that are often out of balance, the people living around it continue to build relationships that transcend differences. Whatever the economic or political circumstances, the ties between people on either side of the border are so fine and so natural as to be almost imperceptible. But to ignore them is folly, whether you’re a screenwriter or the new U.S. president.