This article is adapted from Americas Quarterly’s print issue on Venezuela after Maduro. | Leer en español

El ALTO, Bolivia – As the crowd clapped and sang, five young women wearing stylish versions of the quintessential Bolivian outfit — full flounced skirt, shawl and bowler hat — danced, spinning to show off their brilliantly colored underskirts.

I was attending a fashion show arranged by Ana Palza, a clothing and jewelry designer who emphasizes Bolivian aesthetics. The dizzying swirl of the women’s skirts, or polleras, fit right in with the building around them, itself a Technicolor concoction in bright greens and oranges drawn from the colors of indigenous weaving. The audience snacked on crackers made of quinoa and other Andean grains.

Bolivia has changed, Palza told me, gesturing at the scene that combined indigenous traditions with a new confidence and wealth.

“There used to be so much discrimination, and not so much money,” she said. “People are freer now; you see women in polleras everywhere, with money to spend, showing off their style with pride. There is no going back.”

Nowhere is this change as tangible as El Alto. This bustling city of more than 1 million mostly indigenous people, perched on a high Andean plain more than 13,000 feet above sea level, played a crucial role in the popular uprising that brought Evo Morales Ayma, Bolivia’s first president of indigenous descent, to power in 2005.

A view of El Alto from a new cable car constructed by Morales

A view of El Alto from a new cable car constructed by Morales

Since then, an economy lifted by the rising prices of Bolivia’s gas and mineral exports has soared. Consumer demand boomed, and Morales’ redistributive policies helped share the bounty. More than 1.2 million people, or roughly 10 percent of the population, has joined the middle class — helping Morales win re-election in 2009 and again in 2014.

Today, however, El Alto is restive.

Many remain grateful to Morales for dramatically changing a country where two-thirds of the population is of indigenous descent, but the tiny elite was almost always of European origin. Women wearing polleras, once shunned in public spaces, now occupy prominent positions in politics and commerce; fancy restaurants specializing in uniquely Bolivian ingredients are opening up in exclusive neighborhoods.

Throughout El Alto, hundreds of ornate new homes also testify to the rise and empowerment of an Aymara bourgeoisie. Many are designed by Freddy Mamani, Bolivia’s most renowned architect, whose use of serpents, condors and pumas on façades and interior friezes are inspired by the pre-Incan ruins of Tiwanaku, some 30 miles away near the shores of Lake Titicaca. It’s no coincidence that Mamani’s first “Andean-style” building was inaugurated in the same year Morales came to power.

“We wanted to reflect our culture, who we are, our capacity,” said Joaquín Quispe, a chef, whose family commissioned one such home from Mamani. “We always had the talent. We just lacked the opportunity.”

The interiors of Mamani’s buildings often draw from the vibrant colors of indigenous weaving

The interiors of Mamani’s buildings often draw from the vibrant colors of indigenous weaving

Yet despite these achievements, many in El Alto are turning against the president — specifically, his efforts to seek an unprecedented fourth term in office. In February, El Alto residents joined in protests demanding that Morales respect a 2016 referendum in which voters rejected changing the constitution to do away with term limits. Many carried signs declaring “No means no” and “Respect my vote.”

When I asked Alteños, as the city’s residents are known, about Morales, a great many — from a hat seller in a sprawling outdoor market to a weaver who makes alpaca shawls and a street vendor hawking hard candy on a corner — answered with the same refrain. It was as affectionate as it was clear: “Que descanse.” Let him rest. Let someone else have a chance to govern.

These people were all Aymara, all still hanging on the narrow ledge that separates the nearly middle class from the destitute in what remains South America’s poorest country, with a per capita gross domestic product (GDP) just half of neighboring Brazil’s. All of them were dependent on Bolivia continuing the transformation Morales has begun. Yet they were all ready for a new president.

“We raised our voices”

To learn more about Morales’ appeal, and why it was slipping even among those who have gained the most from his time in office, I went to El Alto’s university. If the city serves as a political compass for Bolivia, the Universidad Pública de El Alto (UPEA) is its needle, pointing the way.

It was the beginning of the semester. Hipsters in tight jeans and fashionable glasses were mingling with young women in bowler hats — the children of El Alto’s middle classes. Sitting outside and watching them mill about, Ronald Bautista, a journalism professor, began telling me about the days when this same campus exploded in protest during the turbulent years before Morales’ first election.

The return of democracy to Bolivia in the 1980s led to years of instability and a rocky economy that did not improve the life of most Bolivians. Discontent exploded in 2003, when Gonzalo Sánchez de Lozada, a U.S.-backed president who spoke Spanish with an American accent, announced unpopular plans to export Bolivia’s natural gas to the United States through Chile. Alteños marched in protest. Like the Bolivian poor everywhere, they did not have adequate access to fuel, although it was produced in the country, and had to stand in line to buy their yellow canisters of cooking gas.

The ensuing violence left some 60 people dead, most of them in El Alto. Although UPEA was only three years old then, students and professors led protests and suffered heavy casualties. Sánchez de Lozada’s resulting downfall was a source of pride: It revealed the political power of the university, the town and the largely indigenous population that called it home, Bautista said.

“We raised our voice,” said Bautista, who is also of Aymara descent. “We took out a president that didn’t represent us.”

The popular uprising, known as the Gas Wars, paved the way for Morales’ political rise. El Alto was his base in ensuing elections, with 77 percent casting a ballot for Morales in 2005, 87 percent in 2009 and 72 percent in 2014.

The president knew his audience. On the day before Morales was sworn in, he donned the red tunic of pre-Incan priests and addressed Bolivians from an ancient temple in Tiwanaku, promising to roll back 500 years of discrimination and colonization.

He also delivered on the agenda that came out of the Gas Wars. On his 100th day in office, he nationalized Bolivia’s oil and gas reserves, sending the military to secure the fields, and giving foreign companies six months to comply with the new mandate or leave. In 2009, he cried as he unveiled a new constitution that was more inclusive of the indigenous and poor: “Here begins the new Bolivia,” he said.

“Before, the government was by white people, and we were very mistreated,” said Silvia, a woman in traditional dress who sells dried llama fetuses and other items used in ritual Andean practices in the Witches Market in El Alto. “Now things are better for people like me.”

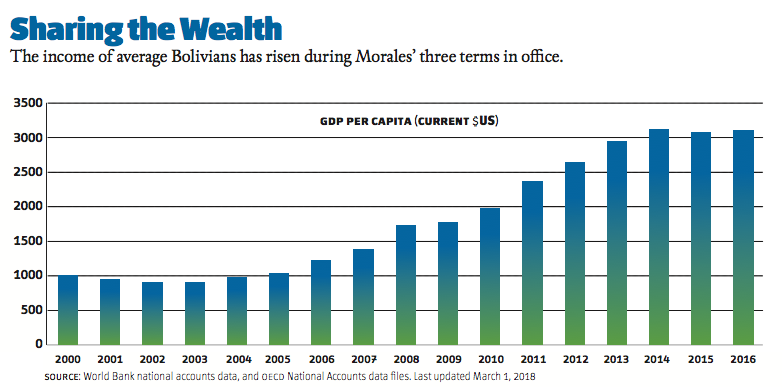

Indeed, since Morales took office, GDP has grown an average of 5 percent per year. The commodities boom helped, but Bolivia’s economy has remained resilient even as other resource-driven economies like Venezuela and Brazil faltered. Morales’ government ran budget surpluses during the good years — 2006 to 2014 — and used the cash flow to pay down public sector debt and build up its international reserves, providing it a good buffer since then.

In 2017, Bolivia managed 4 percent GDP growth, which made it one of the hottest economies in a region that averaged 1.9 percent growth that year. Meanwhile, income redistribution programs helped the average Bolivian share in this bounty: GDP per capita more than tripled during Morales’s tenure, reaching a record $3,393 in 2017.

“Bolivia has always been a very rich country in natural resources, but when we looked at our pockets, we had nothing,” explained former Finance Minister Luis Arce during a public talk. Morales “translated that into benefits for the people.”

Old friends, new rivals

All over El Alto, showy public works projects remind voters of this affluence. Morales’ face is stamped on the doors of cable cars that crisscross over the city and connect it to La Paz — an immensely popular transportation system in the traffic-choked metropolitan area. His figure looms over artificial turf soccer fields, and waves from banners announcing highway repairs, as if to remind voters whom to thank for this largesse.

Despite the bonanza, signs of Morales’ growing autocratic streak are leaving Bolivians concerned. This includes his unflagging support for the less-than-democratic regime in Venezuela, even as its population plunges deeper into a humanitarian crisis. But most consequentially, they worry about measures he is implementing at home, such as stacking the constitutional court with supporters — who then voted to invalidate the 2016 referendum on term limits, drawing round condemnation abroad (including from the Organization of American States), and at home.

“One mandate, two, three — okay, that’s fine,” said Ricardo Nogales, dean of UPEA. “But now? He seems to believe he has absolute power to do anything.”

Morales is also tightening his grip on key sectors of society, and imposing harsh treatment on opponents — even, or especially, on those who were once supporters.

Rapid expansion of gas exploration, soy production and mining — even into national parks — angered environmentalists and indigenous groups. Morales called their criticism part of a Western plot to hamper Bolivia’s growth, and in 2013, his administration passed a law requiring NGOs to comply with government policies — or leave.

“We don’t need NGOs using social and environmental movements to create opposition and conspire,” he told reporters in 2015.

Tensions erupted in August after the administration broke its vow to protect a national park, known as TIPNIS, from being carved in two by a highway. Environmental advocates and indigenous peoples marched on La Paz, and were met with tear gas.

As 2017 progressed, conflicts multiplied. In December, an election of judicial authorities in which candidates were all preapproved by the government turned into a referendum on Morales when the majority of voters cast blank ballots instead.

Before the year was over, a restrictive new penal code brought a wide array of Bolivians to the streets. Among those affected were evangelicals, journalists, trade unionists and doctors, who led a 47-day strike that closed hospitals during the year-end holidays and forced a reversal of the measure.

“There are three areas the government has tried to control — media, justice and civil society,” said Raúl Peñaranda, a Bolivian political analyst and journalist. “It has done so with relative success, with the idea of remaining in power.”

Faced with this mounting threat, a broad cross-section of labor activists, academics, human rights defenders, neighborhood organizations and religious groups have relaunched a political organization famous for fighting the military dictatorship of the 1970s and early 1980s. The organizers kept its name, CONADE, to send a message, said Ricardo Calla, one of the academics involved.

“This is not about right or left anymore,” Calla said. “We want to remind Bolivia that once more, we are running the risk of losing our democracy.

If not Morales, who?

The clearest sign of El Alto’s growing unease with Morales came in 2014, in the form of a young, female and Aymara opposition candidate in the race for mayor. Soledad Chapetón took on an incumbent backed by Morales’ Movement Toward Socialism, or MAS, in 2014, and won a resounding victory by embracing an anti-corruption, pro-democracy message.

Although Morales was re-elected to the presidency that year, opposition candidates took eight of the 10 most important mayor’s seats in the country. Chapetón, a granddaughter of indigenous peasants who was raised in El Alto and favors skinny jeans and stilettos over flouncy polleras, embraced the slogan El Alto con vuelo propio, which loosely translates as “El Alto, flying on its own.”

“It’s not just one man, or one woman, who has the capacity to solve our problems,” Chapetón said. “In Bolivia today we demand respect for democracy.”

Indeed, Bolivian belief in democracy remains healthier, at 59 percent, than the regional average of 53 percent, according to Latinobarómetro, a pollster. Support for Morales, however, is waning. Only 30 percent of the population wanted him to run for a fourth term, an Ipsos poll found in 2017.

Silvia, the amulet and potions vendor in the Witches Market, said the Aymara distrust those who hold on to power for too long. In villages, leadership passes from family to family. Power casts a dark shadow on those who wield it, allowing unseemly alliances and compromises to grow.

Silvia, standing left, sells amulets and potions in the Witches Market

Silvia, standing left, sells amulets and potions in the Witches Market

This is the reason Morales’ supporters are departing: Not because the economy bottomed, or because he has not accomplished what he’d initially promised, though there is discontent in various quarters.

Rather, just as his first election represented an important democratic victory — perhaps the most significant in Bolivia’s modern political history — his push for a fourth term has come to stand for the subversion of those same principles.

Despite this, in February Morales officially launched his bid for a fourth term in 2019.

There’s a chance he might get it. While only 22 percent of the population say they’d vote for him again, that’s enough to earn him the lead, showed a survey published by Página Siete, a La Paz news outlet. This is largely because he has no meaningful opposition as of yet.

His field of rivals is disorganized and weak, made up of ex-presidents — Carlos Mesa led the most recent poll, but has declared he will not run — traditional rivals such as Rubén Costas, governor of Santa Cruz, and the centrist Samuel Doria Medina; and new players like Félix Patzi. None have so far offered a vision that captures the popular imagination.

Traditional political parties, including the long-standing opposition, have lost much of their credibility, said Peñaranda, the analyst. His bet lies in the grassroots movements that are stirring up marches across the country — much as they did during the unrest that preceded Morales’ rise.

“There are many protests, marches that are almost spontaneous, self-organized, often contradictory — almost every day,” he said. “From this effervescence, we’ll get a leader.”

No going back

Even as the grassroots resistance to Morales grows, it is clear the new Bolivia crafted under his tenure is thriving. Politics aside, El Alto is prospering, and planning ahead.

The city is vibrant and young, with seven in 10 residents under 25 years old. The UPEA now has more than 40,000 students, and sends professors into the countryside, offering indigenous communities the skills they need in place, avoiding the disruptive migration. It is also the entrepreneurship capital of the country, with 119,000 businesses, 93 percent of them small- and medium-size, said Roberto Alba Monterey, head of an El Alto business development network.

El Alto has become a sort of dry port, the link between the vast indigenous plains and La Paz, nestled in a canyon below, Alba said. Brushing aside politics, he preferred to discuss what he considered El Alto’s future — its business climate. “We now have our own agenda, our own needs,” he said, listing among them greater dialogue between the public and private sectors, and investment in infrastructure.

This is fertile climate for the architect Mamani, who continues to build himself a future, one Technicolor construction at a time.

We met at a job site, and talked over the din of saws and a tiny radio blaring Spanish pop. While plaster-speckled workers looked on, he put a pencil to a white pillar and sketched out, then and there, the details he wanted them to add. The owner, Aymara like Mamani and the workers, observed and nodded.

In due course, as his reputation and his revenue grow, he wants to build a museum in El Alto to share his vision of a uniquely Bolivian architecture, and to take his work abroad. But he’s patient.

“All revolutions take time,” he said.

It’s true, I thought. Bolivia’s is just getting started.

Photography by Noah Friedman Rudovsky;