This article is adapted from AQ’s print issue on peace and economic opportunity in Colombia

In the small villages around Nuquí, on Colombia’s Pacific Coast, it’s hot, humidity hovers around 100 percent year-round, and sometimes electricity runs for just four hours a day. With limited access to power, residents cannot study at night, run a fan to ease the heat, or even store food.

The less than 3 percent of Colombia’s population that lacks electricity lives mainly in areas of the country that have long been controlled by the FARC and other armed groups, such as Chocó in the Pacific, La Guajira on the Caribbean coast, and Putumayo in the Amazon. In these areas, people cannot charge and use cell phones and even simple mechanization for farming practices is impossible. In indigenous Wayúu communities in La Guajira, there are no electric water pumps, so women and children must walk long distances to artisanal wells or rain-fed artificial lakes to bring drinking water to their communities. Not coincidentally, Colombians without access to electricity also have higher rates of poverty, fewer basic public services, and lower education levels than the rest of the country.

Limited access to electricity is part of a broader problem of insufficient infrastructure that Colombia’s government promised to address as part of its 2016 peace agreement with the FARC. But the challenge is daunting, even by Latin American standards: Logistics represent 15 percent of total production costs in Colombia according to the National Planning Department, the highest such percentage in the region. Such obstacles may not grab the media headlines that, say, disarming FARC soldiers does. But whether the next government succeeds in hooking up more Colombians to the electricity grid, and thus promoting development, will be critical to ensuring a lasting peace.

Colombia’s infrastructure woes can be attributed to multiple factors, from budget shortfalls and corruption to inability to gain consent for construction from local communities. The country’s unique geography presents another challenge: In Colombia, the Andes splits into three mountain ranges that cut across the country, and huge swaths of land are virtually impenetrable jungle.

Under the peace accord, the government specifically agreed to expand electricity coverage, consult with each community to decide which energy source is best suited to each area (for example, by analyzing the amount of solar radiation and wind velocity, the number of homes, and residents’ income and ability to acquire appliances), and provide technical assistance to maintain equipment. In its recent National Development Plan, the government promised to provide electricity access to 173,000 additional households by 2018 through its PaZa la Corriente program — in 2015, 425,000 households in the country still lacked coverage. It also increased resources for the rural electrification fund. The government estimates a cost of $4.3 billion to reach universal electricity access in the country.

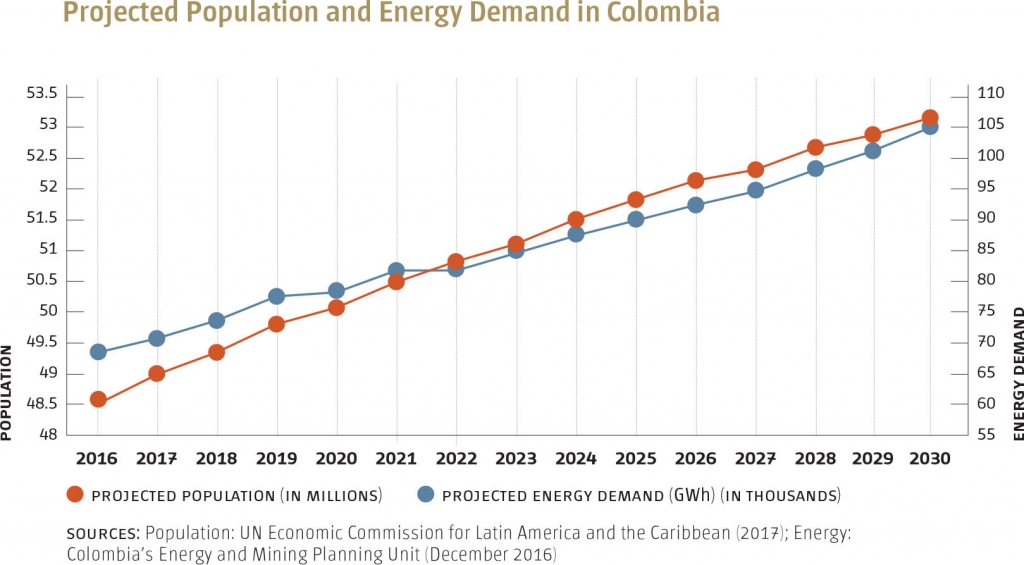

Increased demand complicates these goals. Electricity consumption is set to balloon in the coming decades, due to a growing population and increasing purchasing power. The annual growth rate of energy consumption in Colombia is 5.7 percent, which is higher than the 4.83 percent growth rate of electricity generation, signaling a widening gap between power demand and supply. The bottleneck has worsened in recent years: Between 2009 and 2015, electricity coverage increased by just 1.7 percent while the population grew by 6 percent.

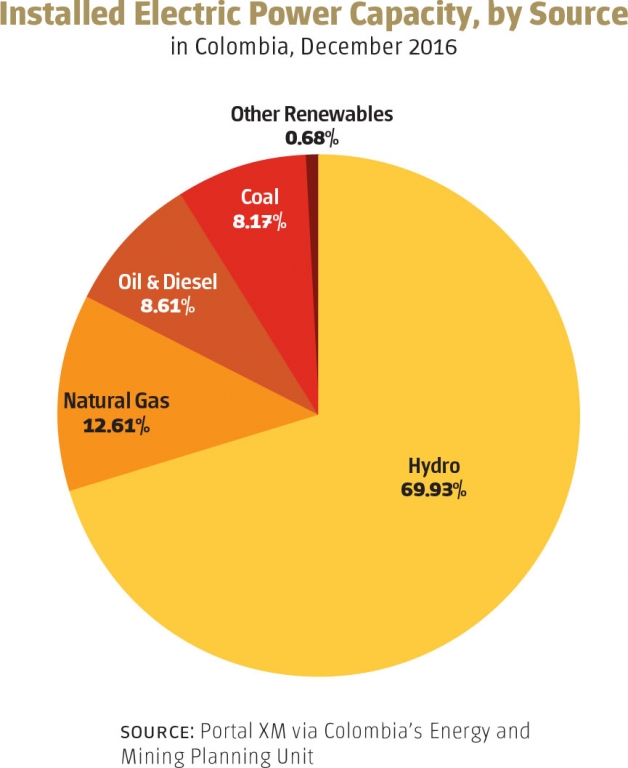

Furthermore, there is disagreement about how Colombia should meet this growing demand. Large hydroelectric dams currently account for about 70 percent of electricity generation, providing a reliable, cheap and low-emissions source of energy. However, there are steep social and environmental costs to building more large hydroelectric dams, including the displacement of communities and damage to the local environment. Generation from non-hydro renewables, particularly wind and solar power, is growing but remains just 1 percent of the total energy matrix. Fossil fuels such as natural gas and coal also provide low-cost, reliable electricity sources, but they undermine Colombia’s climate change mitigation goals. In areas that are not connected to the national electrical grid, most power is generated from highly polluting and expensive diesel generators. One of the government’s goals is to increase off-grid power from small-scale renewable energy projects, which are cleaner and often more economically competitive.

Large hydroelectric dams and unconventional renewables projects alike have been met with local opposition. Plans by Emgesa, a subsidiary of the Italian utility Enel Group, to build a large hydroelectric project in the town of Cabrera were stymied when more than 97 percent of inhabitants voted in a February referendum against any mining or large hydroelectric project in their area.

Jepírachi, a wind project in La Guajira operational since 2004, was shut down for several months in late 2016 and early 2017 due to opposition from the Wayúu indigenous community. The protests were related to a dispute between two Wayúu clans over which group can claim ancestral ties to the land and thus should receive the economic benefits of the project, such as jobs.

As a signatory to the International Labor Organization Convention 169, Colombia requires consultation with indigenous and Afro-Colombian communities before building projects. Since 2013, several municipalities have also used a 1994 law allowing local authorities to hold referendums on projects that will affect their lands to veto energy and mining projects. Many experts claim that the peace process has further emboldened local communities to block infrastructure projects and that President Juan Manuel Santos’ administration avoided taking a position in favor of industry because it wanted community support for the peace process.

There are several steps that the government could take to expand electricity coverage. The government should revise regulations to make it easier for small-scale power producers, especially clean energy producers, to generate electricity and sell it back to the grid. It should also clarify rules on consulting local communities to build energy infrastructure and educate people about the risks and benefits of different types of electricity projects. Electricity access is an important step to help communities in remote areas generate a better income — and ensure Colombia’s rural development.

—

Viscidi is the director of the energy, climate change and extractive industries program at the Inter-American Dialogue