Usually the challenge is to keep students in school. But 18-year-old Douglas Santana is one of thousands of teenagers from more than 70 high schools across the state of Rio de Janeiro who for months refused to go home until the government promised more investment in education.

A senior at Colégio Estadual Visconde de Cairu in the northern suburbs of the state capital, Santana slept every night in a classroom that looked like an army barracks. Behind a row of desks scattered with toiletries was a line of thin sleeping pads and blankets where he and others slept. An overhead window, lacking a curtain, was draped with the Brazilian flag.

“It’s living,” Santana told AQ during a recent tour of his school. “We’ve had back pains, knee pains, but we’re surviving.”

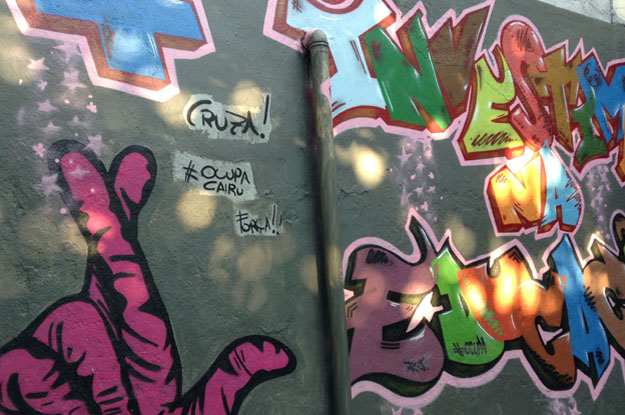

More than surviving, the students’ “occupy” movement has attracted the attention of national and international media and forced the state government to recognize decrepit infrastructure, promise more funding and give students a direct vote in appointing administrators. Inspired by school occupations that took place in Chile in 2011 and in São Paulo last year, students for two months refused to allow administrators inside and instead organized their own courses, hosted public cultural events, and probably got a better lesson in politics than any class could offer.

The standoff came to a head last week. While state authorities in mid-April recognized the legitimacy of the occupation, a state judge on June 1 ruled that occupiers could not block access to other students (some of whom created a “deoccupy” movement) and ordered resumption of formal classes. Seeking to quell the unrest, state education secretary Wagner Victer added that “100 percent” of student demands had been met and negotiations would remain ongoing. But unsatisfied students are still refusing to unlock some schools or leave the state education secretariat (SEEDUC), where they have also been camping out for weeks.

Indeed, the movement won’t be dispersed so easily. It has now spread beyond Rio and São Paulo to other Brazilian states and is considered the country’s largest school demonstration since the restoration of democracy three decades ago. And still unresolved is the source of the unrest: a financial crisis that has spurred the state government to cut education spending and the federal government to propose lifting a constitutional mandate on education funding.

Whatever happens next, the student occupy movement has already been successful in many ways, said Alejandra Meraz Velasco, head of the non-profit education policy institute Todos Pela Educação in São Paulo. “They’re occupying not only the schools but also the newspapers, they are helping to turn education into a priority,” she said in a phone interview. “They are already having a direct effect on public policy.”

The occupations began March 21 at two public high schools in the city of Rio de Janeiro, roughly coinciding with a statewide teachers’ strike over delayed salaries, stagnant wages and work conditions. Over the next month, thanks to an active social media campaign that even shared a “how-to” manual for starting a school occupation, students seized control of more than 70 schools across 23 cities.

The occupying students have complained of staff layoffs, overcrowded classrooms and deteriorating infrastructure, which have been made worse by a 27 percent drop in this year’s state education budget to 7.8 billion reais ($2.2 billion). Annual investment in Rio’s educational infrastructure also plunged 73 percent last year to 92.1 million reais ($26.1 million), according to the state court of auditors. These cuts are especially hard to swallow given the state is spending an estimated $2 billion on the upcoming 2016 Olympics, which has exacerbated the budget crisis by piling on additional debt.

According to official data collected by education monitor Observatório do PNE, only one in four high schools nationwide have adequate infrastructure. A tour of Colégio Estadual Visconde de Cairu revealed broken air conditioners, splintered doors and broken windows. A chemistry lab had gone unused for several semesters because the school lacked enough certified science teachers.

But Santana and others were visibly proud of their efforts to clean up their school. When AQ visited, some students were raking the courtyard garden while others applied a fresh coat of paint to the building. The teachers’ lounge featured a board with news clippings about the occupy movement.

“I’m very surprised I’ve been here for two months,” said 17-year-old Eloiza Bernardino, who has slept at the school almost every day since late March, save for occasional visits home. “The school is functioning better than before. I don’t necessarily want it to end.”

”We don’t want the school to be like it was before; now it’s cleaner,” agreed Santana. “Politics and democracy begin in the school. We want to show that as students in Rio, we deserve a quality education.”

Teachers also supported the movement. Igor Oliveira, 28, who teaches history at two high schools in the city of Rio, was formally participating in the statewide teachers’ strike but continued to visit his students and led lessons on whatever subjects the students requested. The occupy movement also won support from public figures like the musician Marisa Monte, who in early May gave a free show at an occupied high school in the upper-class neighborhood of Gavea.

But not all students were on board. Some took up the position that even a sub-par education is better than no education. “What little we have is being taken away,” said one “deoccupy” protester last month. Some “deoccupy” students even turned to harassment and violence to get their point across. With reported encouragement from SEEDUC, a “deoccupy” movement reclaimed control of at least one school so that it could reopen to all students and administrators.

The judicial decision on June 1 ordered that all schools reopen and that the occupy movement be contained to spaces that do not interfere with normal classes. Judge Gloria Heloiza Lima da Silva also ordered that teachers discontinue their strike, which unions have so far resisted. While some schools remain closed, classes started to resume this week in some of the occupied facilities, including Colégio Estadual Visconde de Cairu. Santana and several dozen others who occupied the school finally went home Monday, and he said classes were resuming Tuesday.

Whether or not this is the end, students have changed the way policymakers must approach education in Brazil.

“We used to think of youths, of students, as a population that was indifferent to school conditions,” said Velasco. “We usually hear they don’t want to study, they don’t care. What we see with this occupation is that’s not the case. They think about school, they have expectations for their schools, they have proposals, they have critical views on what’s happening, and they are willing to fight for their rights.”

—

Kurczy is a special correspondent for AQ.