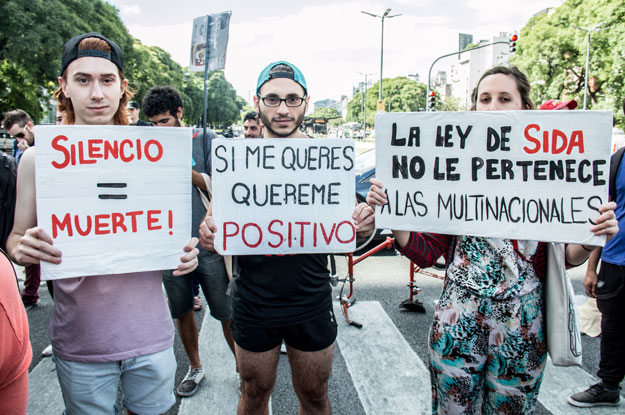

For nearly a year, HIV positive Argentines have endured what advocates call a “crisis” and a “national emergency.” Shortages and delays in the delivery of antiretroviral drugs have beleaguered many who depend on them to stay healthy, sparking public outcry and a protest outside the Health Ministry in Buenos Aires in December.

Since then, officials from the ministry have met with representatives from groups at the front lines of the fight against HIV, and promised that the shortages have been addressed. However, reports of missing medication persist. On Jan. 17, the health minister of Chubut province, in southern Argentina, said in an interview that the national Health Ministry had not sent shipments of drugs for HIV, cancer and tuberculosis. While Argentina has received due applause for providing universal free HIV treatment, advocates of citizens living with the virus are wary of the ministry’s continued assurances in light of the recurrent crisis, which they say is evidence of burdensome bureaucracy and poor leadership.

“We’ve had shortages in the past, but never of this magnitude,” said Lucas Gutiérrez, a member of the National Front for the Health of People with HIV, a coalition of five HIV, women’s and LGBT advocacy groups that formed in response to the lack of medication, which has primarily affected those who aren’t covered by private insurance. “We want solutions.”

After meeting with the National Front group on Jan. 10, Dr. Carlos Zala, the Health Ministry’s AIDS program director, told AQ that there were no actual shortages of HIV drugs in the country. He said reports of missing medication were due to supplier delays and bureaucratic roadblocks, such as shipments of drugs to government pharmacies falling behind as they await various signatures of government officials.

“There isn’t a lack of economic means or political will to purchase the medication,” Zala told AQ. “There have been some administrative delays in its purchase, with some of that responsibility being ours and some not.”

For Marcela Romero, a regional coordinator for the Latin American and Caribbean Network of Transgender People, such delays can be dangerous. Romero told AQ that delays result in patients receiving only a fraction of their prescribed dosage at a time. This heightens the risk of an interrupted dose, which diminishes the drug’s effectiveness.

Romero and other HIV advocates say much of the problem is administrative. Kurt Frieder, executive director of Fundación Huesped, a human rights group focused on HIV/AIDS prevention, told AQ that shortages were partly due to disorganization at the health ministry, noting that the purchase of necessary drugs had “not been made in due time.” Others say the government’s response once shortages have become apparent has been too slow. Matías Muñoz, a national coordinator for the Argentine Network of Positive Young People (RAJAP), said that it took months – and eventually the December protest – for the ministry to respond to their complaints of shortages that they began seeing in March 2016.

While not without its challenges, Zala told AQ that the Health Ministry has been able to provide regular treatment for more than 95 percent of the some 55,000 Argentines with HIV who don’t get treatment through private insurance or social security. The ministry was “very satisfied” with that percentage, Zala said.

For Muñoz, from RAJAP, the goal should be 100 percent.

“Whether it’s one person or a million, Zala’s responsibility is to make sure we all have our treatment,” Muñoz told AQ.

HIV advocates aren’t the only ones to suggest missteps at the Health Ministry in light of recurring scarcity. Dr. Daniel Gollán, the health minister under former President Cristina Fernández de Kirchner, recently called the current ministry the “worst in the country’s history,” criticizing what he said were steps to “shrink and privatize” the country’s healthcare system.

Zala, meanwhile, attributed some of those complaints in part to the country’s political polarization and attempts to discredit the Macri administration.

Most Argentines living with HIV, meanwhile, are probably more concerned with getting their medicine than politics. There may be reason to believe that a recent restructuring at the Health Ministry could help reverse the trend of medicine delays. The resignation of deputy health minister Néstor Pérez Baliño was officially announced on Jan. 9. According to Argentine newspaper Página 12, the departing official said his resignation was part of a division of his Community Health department, which he oversaw and manages 70 percent of the ministry’s budget, into two smaller units. Time will tell whether this will decreases the kind of bureaucracy observers say has hindered the provision of medicine. If not, shortages may keep returning, which could prove a tough pill for everyone to swallow.

—

O’Boyle is an editor at AQ who writes about issues affecting LGBT Latin Americans. He lived in Argentina in 2013.