In January, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) updated its growth forecasts—and the news was not uplifting for Latin America and the Caribbean. Average regional growth for 2015 was revised downward from 2.2 percent to 1.3 percent.

The report forecast that Brazil, the region’s largest economy, would remain stagnant for another year, while the economies of Argentina and Venezuela were projected to continue contracting. Growth rates in other energy-exporting economies (notably Bolivia, Colombia and Ecuador) were expected to fall, as the sharp drop in oil prices will affect investment and export receipts. (The price of a barrel of oil fell from $110 in late June 2014 to below $50 in early January 2015.)

A recovery in growth was projected for several other economies, including Chile, Mexico and Peru. In Mexico, this recovery will mostly come from stronger activity in the U.S. and from a gradual strengthening of domestic demand. Chile and Peru, in turn, are set to benefit from lower oil prices, supportive fiscal and monetary policies and the removal of some short-term brakes on growth (eg., earlier delays in certain Peruvian mining projects). Finally, growth in Central America and the Caribbean was expected to speed up on the back of stronger U.S. growth and declining oil prices.

Unfortunately, new data have maintained a negative tilt since the report was released in January. In Brazil, the fiscal results for 2014 were weaker than expected, requiring an even greater adjustment to reach this year’s stated target. Payment delays and growing legal uncertainties as a result of the unfolding Petrobras corruption scandal are now affecting the country’s main construction companies. In addition, there are energy and water shortages in parts of the country, including in São Paulo, the country’s economic engine; and the risk of near-term rationing has led most analysts to forecast negative GDP growth for 2015.

Meanwhile, the fall in the price of oil seems to be weighing somewhat more heavily than expected on the main energy-exporting economies, even though other countries in the region are primed to benefit. In this environment, analyst forecasts for regional growth have started moving toward—and in some cases, below—1 percent. (The next IMF forecast update, to be published in mid-April, will likely reflect these changes.)

If these projections materialize, 2015 will be the fifth consecutive year of weakening activity in Latin America, with growth rates now worryingly close to zero. Only a few years ago, analysts believed the region had found the formula for sustained rapid growth and social progress. What has happened since?

No More Golden Period

It is now clear that the boom in commodity prices was a crucial determinant of the “golden period” of growth starting in 2004. The decline in commodity prices since mid-2011 has weighed down growth in many South American economies that had previously reached full employment or had even become slightly overheated. Meanwhile, weak global growth held back activity in other parts of the region, including those economies with close trade links to the U.S., such as Mexico and Central America. In this environment, many economies—especially in Central America—continued to build up important fiscal vulnerabilities as public debt levels rose.

If the timing and depth of the region’s slowdown has indeed been closely linked to the decline in commodity prices, that decline can be at least partly attributed to China’s gradual economic slowdown.

Commodity prices have fallen in two phases. Producers of metals (such as copper and iron ore, for which China had become a dominant source of demand) and agricultural goods have seen their export prices decline since 2011. Oil prices, in contrast, held firm, sustaining historically high levels until June 2014. Since then, the price of oil has suffered a sharp decline, which intensified in the last quarter of 2014 and in early 2015.

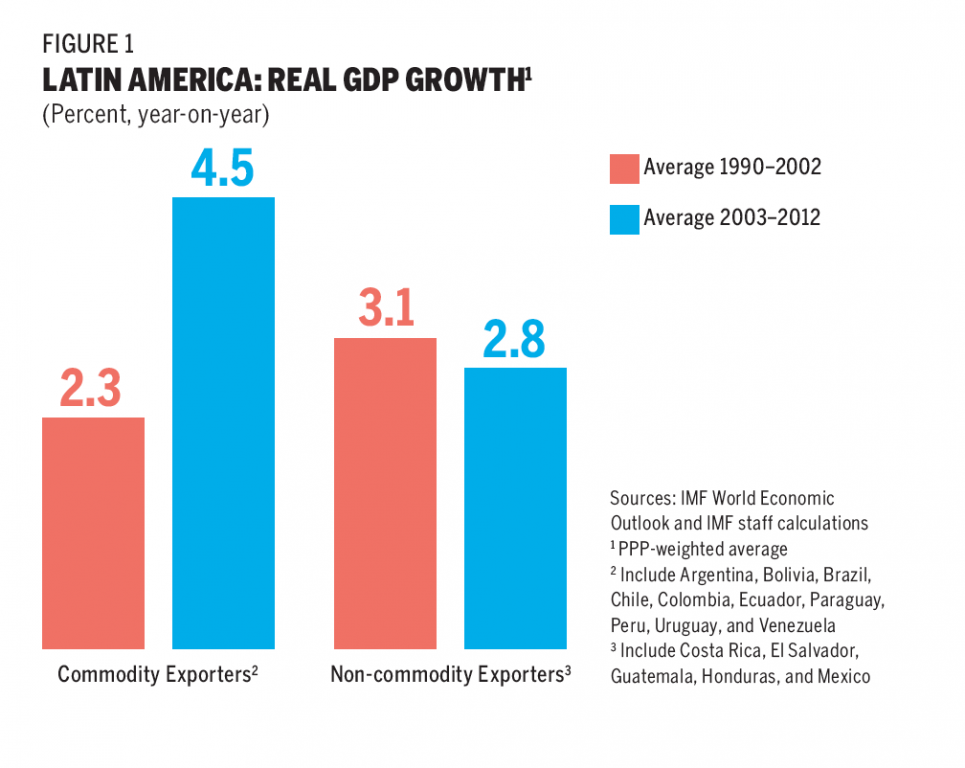

A 2013 IMF Working Paper divides Latin America’s economies into two categories: those that benefitted from the commodity boom and those that did not.1 Countries that experienced a terms-of-trade boom—such as Bolivia, Peru and Venezuela—exhibited higher growth than the rest of the region and bested their own growth rates from the previous decade [see Figure 1].

Strikingly, these economies have also experienced a more pronounced deceleration over the past three years. Evaluating the components of aggregate demand, it is clear that the deceleration has been driven by a drop in investment and exports, whereas consumption and employment have generally proven more resilient so far. Moreover, in those economies where the effects of the commodity boom were amplified by expansionary policies—either by strong public expenditure growth or strong credit expansion—such as Venezuela and Argentina, the deceleration started earlier as they hit capacity or encountered market access constraints.

Countries with weak public finances face the toughest adjustment

Venezuela and Argentina, two countries where government expenditure increased the most in the past decade, today exhibit some of the highest rates of inflation in the world—clear signs of an unsustainable fiscal expansion that has increasingly been financed through domestic money creation. In both cases, expansionary policies started eroding current account surpluses even when commodity prices were still quite high. Compounded by the subsequent decline in commodity prices and the countries’ heavily restricted access to global financial markets, this led to a shortage of foreign exchange—which in turn triggered increasingly onerous restrictions on trade and foreign payments. These restrictions, along with increased policy uncertainty, had a severe effect on private investment and generated economic problems even before the latest worsening in the terms of trade.

In Brazil, the large countercyclical policy stimulus put in place after the 2008 crisis also contributed to widening the current account deficit and to generating inflationary pressures, although to a much lesser extent. On top of this, an overvalued real and the failure to address important structural problems (including infrastructure gaps, heavy bureaucratic burdens and a very complex tax system) hurt industrial activity and private investment.

Given the continued rise in public debt and the persistence of inflation rates well above the official target, policies cannot be loosened any more today to support aggregate demand. Rather, the priorities are to rebuild investor and consumer confidence, to shore up the credibility of the institutions and rules governing fiscal and monetary policy, and to alleviate supply-side constraints, such as weaknesses in the business environment.

In Argentina, Venezuela and Brazil, economic deceleration started earlier and was more pronounced than in Bolivia, Chile, Colombia, and Peru—countries where policies have been less procyclical. Essentially, authorities in these countries could afford to smooth the effects of lower commodity prices because they had built up buffers during the good times.

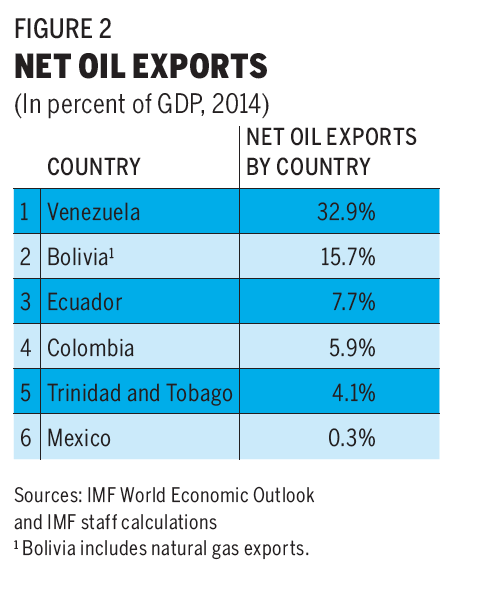

Now, the second stage of the commodity price adjustment is under way. The price of oil dropped more than 50 percent between June 2014 and January 2015. Six economies are net oil exporters, Venezuela being the most exposed, with a net oil export to GDP ratio surpassing 30 percent, followed by Bolivia, Ecuador, Colombia, Trinidad and Tobago, and Mexico [see Figure 2].

Although Mexico’s oil production has fallen significantly in the past 10 years and domestic fuel consumption has increased, oil remains a relevant source of public revenues. Therefore, the price drop puts pressure on public finances. Even so, Mexico should finally see some pick-up in growth after having consistently disappointed expectations in recent years. (Indeed, Mexico has been one of the region’s slowest-growing economies for the past 20 years.)

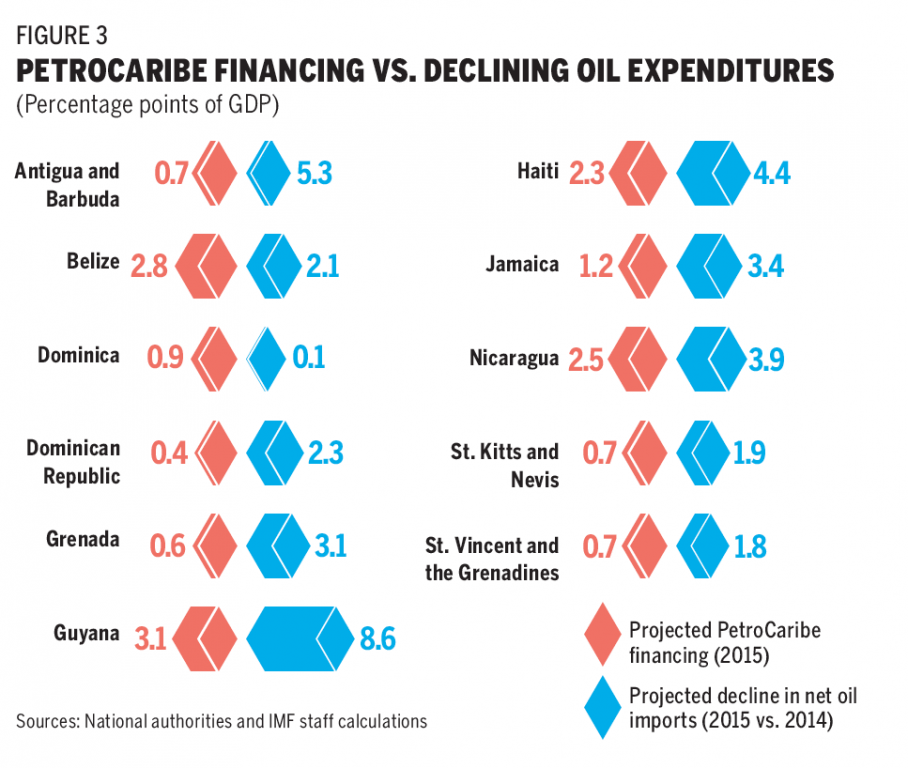

On the upside, oil-importing economies in Central America and the Caribbean stand to gain from the drop in oil prices. However, some of these gains could be undermined by a loss of concessional financing from Venezuela. Through the PetroCaribe program, Venezuela has been selling oil to partner countries on concessional terms. The government so far has maintained its commitment of continued support, yet the dire economic and political situation in the country might prompt a sudden stop of these flows.

For many countries, oil-related loans from Venezuela represents a significant source of financing for their respective current account deficits [see Figure 3], though the scale of that financing is typically smaller than the overall savings on the countries’ oil import bill due to lower prices. Consequently, from a national perspective, the net effect of these two factors should be positive. However, it’s not quite that simple. The benefits from lower oil prices in these countries will mostly affect the private sector, whereas the reduced financing from Venezuela will typically hit the public sector. Countries with diverse sources of financing will fare better than those facing tighter constraints; the latter may need to make important adjustments, including by reducing their current fiscal deficits.

More generally, the domestic economic effects of the fall in international oil prices depend critically on how domestic fuel prices are adjusted. Many countries in Latin America are allowing prices at the pump to decline in response to cheaper global oil. In other countries, however, fuel prices have been closely regulated in the past, and often kept below market price levels. Against this backdrop, some country authorities are now choosing to limit the decline in end-user fuel prices. While this reduces the potential boost that lower prices could bring to the private sector, it will end up strengthening the public finances, or in countries where state-controlled oil companies provide public fuel subsidies, the balance sheets of those companies.

Energy sector investment takes a hit

The decline in oil prices could also affect growth through its impact on investment in the energy sector. One would expect this to most strongly affect current net oil exporters. However, even some countries that are not currently important net oil exporters but have significant potential for future oil and gas development projects—such as Argentina, Brazil and Mexico—will also feel the effects of today’s lower prices. Indeed, Brazil’s Petrobras and Mexico’s Pemex—both state-owned oil companies—have already announced large capital expenditure reductions for 2015.

As the region adjusts to the reality of lower commodity prices, two other external forces will affect its economic performance: the uptick in U.S. economic growth—projected in January at 3.6 percent for 2015, up from 2.4 percent last year—and the evolution of international financial conditions.

IMF analysis regarding the effects of the U.S. recovery on Latin America shows a clear differentiation among subregions. Mexico, Central America and the Caribbean, whose economies are most closely linked with the U.S., are set to benefit the most, with growth likely to improve by more than half a percentage point for every percentage point increase in the U.S. growth rate.

In most of South America, by contrast, positive spillovers from U.S. economic growth are modest. In fact, if the impending rise in U.S. interest rates were to generate significant market turbulence and cause financing conditions to tighten sharply, the net effect on some South American countries could well be negative.

Reinvigorating weakened economies

As a result of these external forces and the apparent return to the mediocre growth rates of the past, important questions arise. What can countries do to revitalize activity? And how can the region continue to improve its social conditions in a lower-growth environment?

Regarding growth, one historical problem is the prevalence of low investment and savings rates in Latin America. For example, average savings and investment rates for the region’s largest economies over the past decade were 22 percent and 20 percent of GDP, respectively, well below the corresponding figures for emerging economies in Asia (33 percent and 30 percent of GDP). These shortcomings were blurred by the large income gains associated with the commodity boom that temporarily allowed investment to increase on the back of windfall savings.

In a new environment of lower commodity prices, countries across the region seem to be reverting to their historically low levels of investment and savings, along with low overall productivity growth. How to address these challenges would require more space than is available here. But in general, education, infrastructure, innovation, the ease of doing business, security, the rule of law, and corruption are all clear areas for improvement across the region.

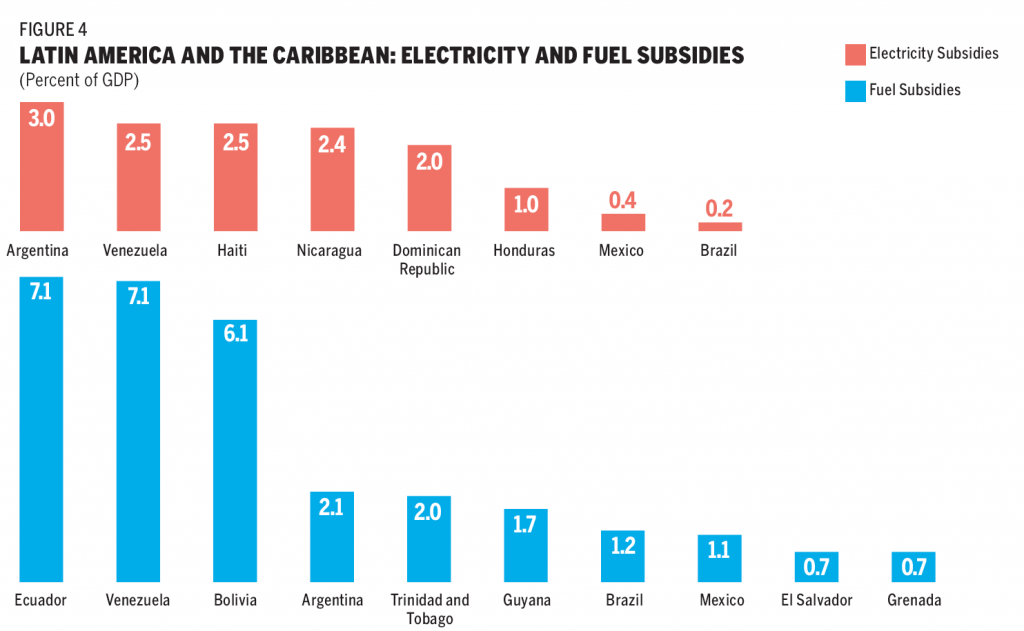

Protecting and deepening the gains achieved on the social front in the past decade is also critical. In many countries, there is ample scope to increase the efficiency of social programs and target them more precisely to vulnerable groups in society. One prominent area of opportunity is phasing out energy subsidies. These subsidies are very large in many countries [see Figure 4] and are clearly regressive and poorly targeted, in that they benefit well-off households the most. Falling energy prices bring with them the opportunity for energy subsidy reforms.

The next few years will be very challenging for Latin America. Many countries will have to navigate an environment of low growth, tighter budget constraints and increasing social demands. In these circumstances, it will be even more critical to address long-standing supply-side bottlenecks and, through structural reforms, create the right conditions for higher savings, investment and productivity growth. Meanwhile, countries will need to preserve macroeconomic stability by keeping fiscal deficits in check, by maintaining low inflation, and by limiting external imbalances. Flexible exchange rates can play an important role in supporting the adjustment to more challenging external conditions.

Many countries in the region are well prepared to handle this transition, but others might face a rough period where the return of macroeconomic crisis would not be a surprise.