In March, the European Union (EU) and the Cuban government announced a renewal of bilateral talks on trade and investment. Lured by Cuba’s proposed social and economic reforms, including a new foreign investment law, the expansion of self-employment, and loosened travel restrictions, the EU agreed to return to the negotiating table for the first time since the establishment of the Common Position in 1996, including human rights and democracy in the discussion on improved economic relations.

But it would be misguided to assume that the Cuban reforms are a sign of genuine change within the regime. Rather, they represent an attempt to adapt the revolution’s principles of “protect and perpetuate” to changing circumstances: a strategy that has allowed the regime to survive repeated economic and political shocks over the past 55 years.

Less than a decade ago, then-President Fidel Castro was singing a different tune about cooperation with the European Union. During a speech on July 26, 2003, he declared, “The government of Cuba, out of a basic sense of dignity, relinquishes any aid or remnant of humanitarian aid that may be offered by the European Commission and the governments of the European Union[….]Cuba does not need the European Union to survive, develop and achieve what you will never be able to achieve.”

Trusting that this logic long-held by the Castros—then Fidel, now Raúl—has changed will cost current negotiators and potential investors dearly.

If the talks continue, it wouldn’t be surprising if—soon after the contract with the EU is signed—European businesspeople are arrested for corruption, bank accounts are frozen, and Cuban officials start employing, again, their bullying strategy of “support me unconditionally, or go with your investments somewhere else.”

Christian Leffler, the EU’s managing director for the Americas of the European External Action Service, said during his April visit to the island that the human rights debate will not be among the main topics at the relaunch of the conversations. Is the EU being flexible or simply conceding a pivotal democratic issue to avoid confrontation?

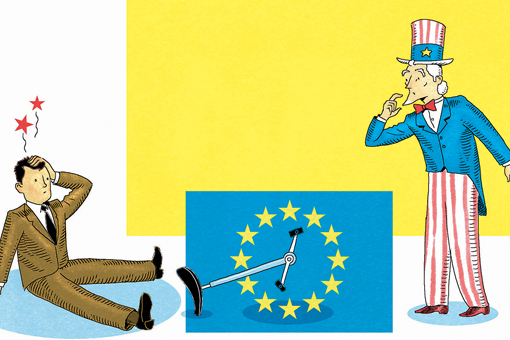

When the bilateral talks were first announced, Cuban Foreign Minister Bruno Rodríguez said he hoped a rapprochement between Cuba and the EU could create an opportunity to move the needle on U.S.-Cuba relations. But while the issue of human rights appears to be, at best, a secondary priority for the EU talks, its absence is an absolute deal-breaker for the U.S., where the political debate around Cuba is already polarized.

For decades, various U.S. administrations have made the defense of human rights for Cuban citizens a priority in U.S. relations with the Cuban regime and used the embargo as a tool to pressure the regime. As the Helms-Burton Act of 1996 states, the U.S. has a “moral obligation to promote and protect human rights and fundamental freedoms.”

This has left Cuba-U.S. relations at an impasse. With the embargo still in place and tension still simmering over jailed USAID contractor Alan Gross, the odds of strengthening diplomatic ties are slim to none. Unless the White House decides to turn a deaf ear to the opinion of the majority on the island and change the nature of its relationship with the Castros—through executive action, without a consensus among the different actors linked to this issue—the needle won’t move.

Moreover, any possibility that Cuba might be moved off the State Department’s State Sponsors of Terrorism list was extinguished when the North Korean ship Chong Chon Gang was discovered last July to be carrying tons of undeclared weapons from Cuba to North Korea. Cuban authorities claimed the cargo was “obsolete defensive weaponry” that was going to be “repaired and returned” (shipped undeclared and hidden under sacks of sugar, of course).

The fact is, the EU has placed itself in a position of negotiating with a government that has repeatedly attempted to violate international laws, and that routinely eavesdrops on its guests, recording all conversations and videotaping the activities of all leading who visit the country.

It will take a lot more than superficial reforms to bring the U.S. to the table.

Those who fear losing investment opportunities to the EU or other countries are ignoring the fact that the terms of foreign investment are still mediocre at best, even after the new foreign investment law that went into effect in June. For example, while foreign companies will now be allowed to own a 100 percent stake in a venture on the island, they will be denied the tax breaks that are afforded to joint ventures with the Cuban government.

American policymakers should remember that when the current regime collapses under internal and external pressure, Cuba’s natural market (given its geographical situation, and historical and family ties) will be the U.S., to which it will be inevitably and quickly drawn. If the U.S. maintains its current diplomatic stance, political and economic ties with a future democratic Cuba will be assured.

There’s no doubt that U.S. government officials will be watching the Cuba–EU talks closely. For now, though, it will be smart for the U.S. to keep its distance from these negotiations, which have been tainted from the very beginning.