Much is made of the perils of ending NAFTA for Mexico, and rightly so. The 23-year-old agreement has helped the nation not only boost trade but also transform its economy, moving from a commodity to an advanced manufacturing exporter. With 80 percent of its exports headed north, even the threat of change has hurt Mexico’s currency, limited its ability to attract foreign direct investment, and cut the country’s current and future economic growth.

Largely overshadowed in all the tough renegotiation talk is what might happen to the U.S. companies that sell into Mexico’s $1 trillion dollar economy and to its 120 million consumers. With NAFTA’s zero tariffs and legal guarantees, the U.S.’ southern neighbor has become a top export market, buying over 15 percent of everything made in America and then sold abroad, topping $230 billion in 2016.

Best known and most tweeted about are the industrial behemoths – Caterpillar, Ford, General Motors, and Medtronic – as a part of their tens of billions of dollars in market capitalization are backed by sales of machines, cars and medical equipment to Mexico. More vulnerable are thousands of small and medium-sized American businesses, which are more likely to export to Mexico than anywhere else in the world. All told, these companies big and small employ some 5 million Americans, and help support hundreds of communities across dozens of states.

This could all change if NAFTA ends. Tariffs on U.S. exports would rise to an average 7 percent; on some crops and apparel fees would jump to double digits. These new charges would make corn, soy, beef, or pork from far away Argentina and Brazil more economically, not to mention politically, attractive. The tariffs would also enable EU made helicopters, generators, engines and other car parts to edge out American producers, gaining market share. All told, U.S. companies would be at a disadvantage vis-à-vis the past and vis-à-vis the 45 other nations that have free trade agreements with Mexico, and the end of NAFTA would level the playing field for those still without a preferred arrangement.

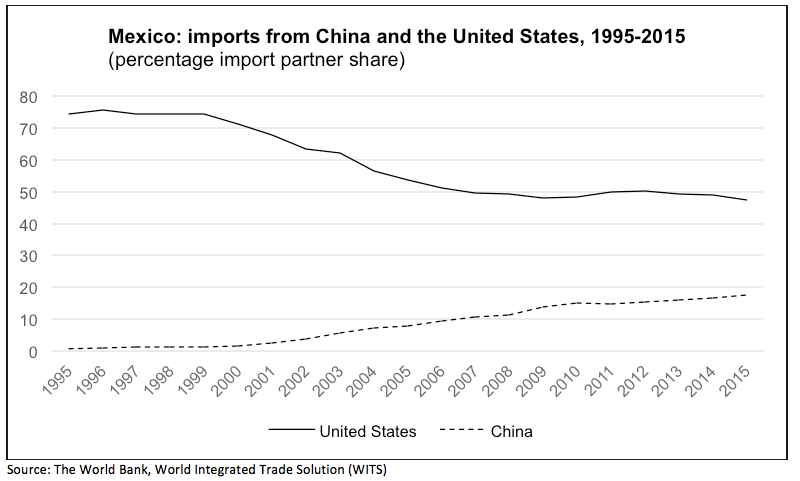

By far the biggest winner will be China. Even with tariffs, Chinese goods already flood the Mexican market, selling billions in cellphones, computers, TV parts, and innumerable tchotchkes. The Asian giant has been stealing market share from U.S. makers since they entered the WTO in 2001, cutting U.S. sales to Mexico from 4 out of every 5 dollars of imports to less than 1 in 2.

Chinese competition has decimated America’s former dominance in furniture, clothing, office machines, computers, and phone sales. Next could be cars, the most iconic of North America’s manufacturing industries. Until now largely satisfied with the voracious demand at home, its domestic car makers are beginning to dip into global markets. And U.S. President Donald Trump’s tough talk looks to speed this looming challenge. When Ford pulled out of a planned $1.6 billion plant investment in San Luis Potosí in January, China’s state owned JAC Motors came in, now planning to make its first North American SUVs.

While exports south fuel just a small slice of the $18 trillion dollar U.S. economy, NAFTA’s demise will matter for these linked workers, companies and communities. Texas would fall the furthest, as Mexico buys over a third of its exports, powers more than 5 percent of its GDP, and supports nearly 500,000 jobs in this Republican stronghold. Also on the line would be the industrial heartland states of Michigan, Ohio and Indiana, farming states of Nebraska and Iowa, and the rest of the border.

The often cited statistic that 40 cents of every Mexican export dollar north is created by U.S. workers is real, as thousands of companies have invested tens of billions in both nations, creating North American supply chains to make cars, computers, TVs, planes, washing machines, MRIs, defibrillators, and a whole host of other products. And even as some jobs in America’s rust belt have disappeared, many others have stayed or been created precisely because of these investments to the south. By spanning the border, factories make products they can sell globally – increasing the overall economic pie then shared between companies and workers in both countries.

As the United States pushes forward with its renegotiation, it shouldn’t lose the larger guiding philosophy behind NAFTA, namely the recognition that a stable and prosperous North America helps all three nations.