Well, now it’s officially part of the judicial record: Lula is in a category all his own.

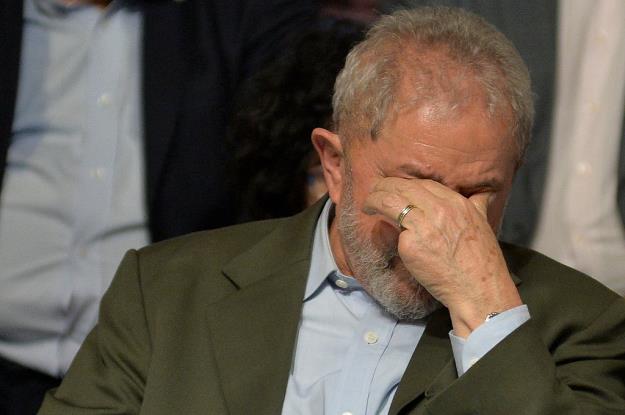

The most striking aspect of Wednesday’s ruling against former president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva was the judge’s admission that Lula warrants special treatment. This, more than any other detail, suggests the man who has dominated Brazilian politics for the last 30 years may yet avoid jail – and even return as president in 2018, as he vowed to do in an emotional morning-after press conference.

Federal Judge Sérgio Moro, the “untouchable” public face of the so-called Car Wash corruption probe, ruled that Lula was guilty of accepting $1.2 million in favors from engineering company OAS, and sentenced him to nearly 10 years in prison.

However: Lula will remain free while he appeals his case – a process that could take up to a year. In the final paragraphs of his 218-page ruling, Moro wrote that because of Lula’s record of allegedly trying to intimidate the court, and instruct third parties to destroy evidence, “it would potentially be worth considering” ordering the ex-president to jail during the appeals process. But Moro concluded that, “considering that the preventive arrest of an ex-president of the Republic would involve certain traumas, prudence recommends” that Lula not be imprisoned for now.

Yes, Moro blinked.

It’s important not to overstate the importance of this. In dozens of cases over the past three years, Moro has only ordered one defendant to jail pending appeal – Fernando Moura, who broke his plea bargain deal by lying in court. Moro was also clearly bending over backwards to appear reasonable, given the relentless efforts by Lula’s lawyers to portray him as politically biased, as well as Brazilian media’s coverage of the case as a World Wrestling Federation-style grudge match of Moro versus Lula. “The ruling does not bring this judge any personal satisfaction,” Moro wrote.

At the same time, it’s hard not to see in Moro’s words at least a trace of the deference to power, and instinctive preference for compromise, that has long characterized Brazilian political culture – and may ultimately be Lula’s salvation.

This is often hard to define, and harder for outsiders to understand. Some see it as a clubby back-scratching code that has guaranteed impunity among Brazil’s elite for centuries. Others (especially those on the inside) argue that a culture of compromise, even among bitter rivals, is what has held together a continent-sized country riven by terrible inequality and violence, and avoided the destabilizing polarization long seen in peers like Argentina, Venezuela or Chile.

Moro’s work since 2014 has at its core been about ending Brazil’s culture of impunity, and he has made extraordinary progress. In Wednesday’s ruling, he quoted the legendary English 17th century historian Thomas Fuller: “Be you never so high the law is above you.”

But Lula may prove a bridge too far. In practice, even Lula’s staunchest political rivals have admitted he merits special caution – or “prudence,” to use Moro’s word. The 71-year-old former labor leader oversaw a long economic boom from 2003 to 2010, and left office with an approval rating of almost 90 percent. While tarnished since then by Brazil’s economic collapse and the Car Wash case, Lula remains a folk hero to many. He leads polls for elections next October, and is rising as some Brazilians hunger for a return to the stability and prosperity of the 2000s, ethics be damned.

If even “Brazil’s Eliot Ness” was moved by such considerations, imagine the reaction of higher-ranking judges who are either more sympathetic to Lula himself, or more attuned to the old Brazilian ways. The case now moves to a three-person appeals court in Porto Alegre that typically takes 10 months to a year to hear cases. That means they will presumably hear the case just as the 2018 campaign is reaching its nadir. Will they really have the guts to jail him at that moment, or will they also bow to the risk of “certain traumas?” There is also persistent speculation that the Supreme Court, the majority of which was appointed by Lula or his party, could find a way to get Lula a “waiver” and still run for office, even if convicted.

If that sounds ludicrous, consider that this is Brazil in 2017 – a legal free-for-all in which the current president has been charged with corruption, most of Congress faces the prospect of criminal charges, the economy is trapped in its worst recession in a century, and the three branches of government are engaged in an open “war” for primacy and survival. Some of Brazil’s strictest constitutionalists are urging for the Constitution to be shoved aside so that early elections can be called to end the chaos. In this context, a little jeitinho – the classic Brazilian term for finding a way around the rules – to keep Lula free seems completely plausible.

The current morass also explains why Wednesday’s ruling is unlikely to further tarnish Lula’s political standing. The case centers on a beachfront apartment that OAS allegedly gave to Lula and his family in return for a Petrobras contract. But this – let’s be honest – is child’s play compared to the charges against numerous other Brazilian politicians, including the former right-hand man of President Michel Temer, who was caught on video carrying a suitcase of cash.

If there was an era where Lula could be portrayed as the unambiguous villain in a battle between good and evil, it passed in mid-2016, when most of Brazil’s establishment threw its support behind Temer. While prosecutors in Curitiba have repeatedly insisted that Lula was the godfather behind the whole Petrobras scheme, Moro explicitly punted on that question in Wednesday’s ruling, saying it wasn’t “necessary” to decide for now.

It’s true that Lula still faces four other criminal cases – all of which are seen by legal analysts as stronger than the beachfront apartment allegations. But this was the only one likely to result in jail before the presidential campaign. In debating Lula’s fate, some Brazilians have adopted the saying “Ou preso, ou presidente” – “Either jail, or the presidency.” In the long run, I’d still bet on the former. But he may get a shot at the latter first.