AQ invited former foreign policy officials from the Trump and Biden administrations to offer their analysis of what another term for their former boss might look like. The articles were finalized in June. To see the Biden essay, click here | Leer en español | Ler em português

On February 4, 2020, in the final State of the Union of his first term, U.S. President Donald Trump delivered the most Americas-centric address of any modern-day presidency. Sadly, those remarks stand in stark contrast to President Joe Biden, whose recent, and perhaps final, State of the Union in 2024 did not contain a single direct reference to Latin America and the Caribbean.

In 2020, Trump celebrated the success of the new U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA), a gold standard for 21st-century trade deals based on the principles of fairness and reciprocity, and the protection of intellectual property. He also lauded the “historic (migration and asylum) cooperation agreements with the governments of Mexico, Honduras, El Salvador and Guatemala,” which had contributed to a 75% decline in people apprehended illegally crossing the U.S.-Mexico border over the previous eight months.

Trump expressed unequivocal support for “the hopes of Cubans, Nicaraguans and Venezuelans to restore democracy,” and heralded how the U.S. was “leading a 59-nation diplomatic coalition against the socialist dictator of Venezuela, Nicolás Maduro.” That was the largest such coalition of like-minded countries in support of democracy in Latin America’s history. Meanwhile, in the gallery, to the surprise of all, Trump directed attention to the presence of then-President Juan Guaidó, head of Venezuela’s National Assembly and its constitutional leader, who was welcomed by the U.S. Congress, with the biggest bipartisan applause of the night.

And we were just getting started.

The core of Trump’s approach to Latin America and the Caribbean was the inextricable link between U.S. national security and mutual economic growth. In December 2019, he approved a whole-of-government initiative called América Crece (Growth in the Americas), focused on the design and implementation of energy and infrastructure investment frameworks, which would identify new markets, create a tangible pipeline of deals, and harness private capital from the U.S., while weaning countries from their dependence on multilaterals and Chinese state-owned entities. One year later, nearly half the countries in the region had signed América Crece investment frameworks, while the last Belt and Road agreement with China was inked in 2019. For the first time in a decade, the U.S. gained ground and boxed China out of the region by a score of 15-0—not including two fully negotiated frameworks that were left signature-ready—and identified nearly $174 billion in investment opportunities.

Trump further believed that peace through strength should be prioritized in the Western Hemisphere, as doing so would save more American lives than anywhere else in the world. As an example, on April 1, 2020, he proceeded to announce the most powerful U.S. military law enforcement operation in the Americas since the 1980s to combat the flow of illegal drugs and degrade transnational criminal organizations across the Caribbean and Eastern Pacific coasts. In the first three months of this enhanced counter-narcotics operation alone, the result would be more than 1,000 arrests and the interdiction of 120 metric tons of narcotics.

In fairness to Biden, he had little to tout regarding the Americas in the 2024 State of the Union due to his misguided policies. Furthermore, under his watch, the world is once again consumed by global crises in Ukraine, the Middle East and the South China Sea. Foes of the U.S. in Russia, China, Iran and North Korea have seized on the distractions and joined forces to dilute the capacity of the U.S. to respond to simultaneous global conflicts.

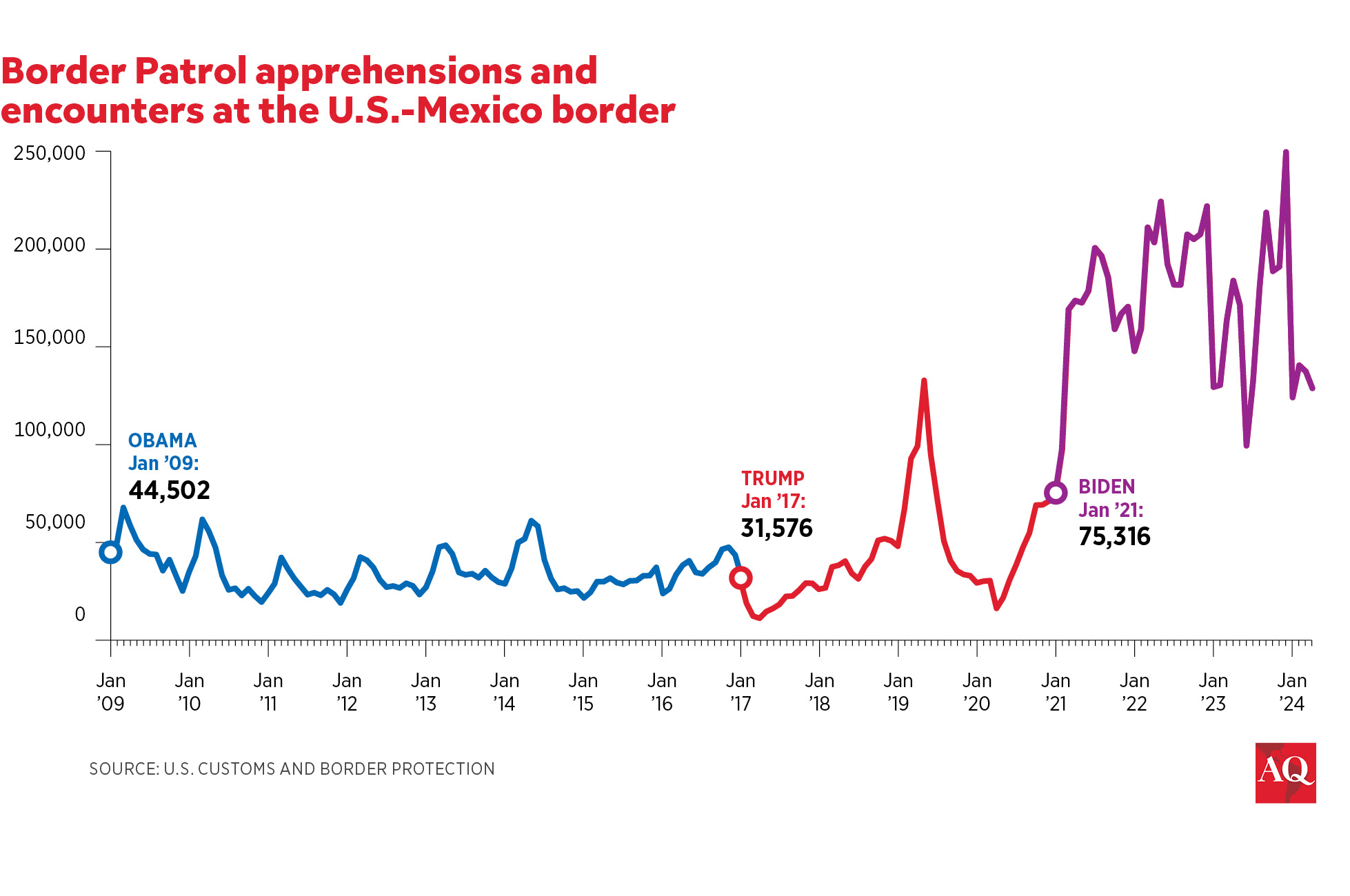

In his first 100 days, Biden signed 12 executive orders on immigration and the border—10 of which were direct reversals of Trump’s successful policies. These were heralded as a “new era” for immigration policy in which Biden proudly proclaimed, “I’m not making new law; I’m eliminating bad policy.” If the goal was to eliminate the significant drops in illegal crossings and the ability to secure our border, Biden surpassed all expectations.

Illegal border crossings have shattered every possible record under the Biden administration.

Predictably, illegal border crossings have shattered every possible record under the Biden administration. According to U.S. Customs and Border Protection, the Border Patrol had nearly 10 million “encounters” with immigrants crossing the border illegally from fiscal 2021 through May 2024. This has grown into a fullscale crisis, affecting countries across the hemisphere, with major security implications, including terrorism, narcotics and human trafficking, and the regional expansion of new criminal networks, such as Venezuela’s dangerous Tren de Aragua.

Meanwhile, the cornerstone Latin American policy of the Biden administration has been the normalization of the authoritarian regime of Maduro in Venezuela, a step akin to the sloppy abandonment of our allies inside Afghanistan. It began by sidelining National Assembly leader Guaidó and leaving his wife and two young daughters forced to flee on foot for their safety without protection across the border to Colombia. Biden commuted the U.S. prison sentences of Maduro family narco-traffickers, and inexplicably pardoned and enabled the return to Venezuela of his most able henchman and proxy with Iran. Venezuela’s fate is now left to a failed U.S.-sponsored deal in Barbados and—yet again—sham elections with an opposition undermined from the start.

The latest crisis near our shores in Haiti is the result of further policy malpractice. Since the assassination in 2021 of President Jovenel Moïse, the political and security crisis has spiraled as violent gangs hold grip over Port-au-Prince, destroying any remaining semblance of institutionality and now murdering U.S. missionaries. In response, the Biden administration has relegated policy to rhetoric in support of a flawed provisional electoral process and a Kenyan-led security force that will further inflame tensions. Clearly, the domestic backlash to foreign-led security forces following the disaster of the 2010 Nepalese-led security force has been forgotten.

And Nicaragua has now transitioned to a full-fledged totalitarian dictatorship, the only one in history with a free-trade agreement with the U.S. The absolute clampdown and forced exile of civil society and clergy leaders signals the complete impunity from which Daniel Ortega’s regime benefits. Managua has become the political epicenter of Russia in the Americas, and a lucrative air bridge for over 1 million Haitians, Cubans, Chinese and Africans to begin their illegal land journey to the U.S. southern border. To think that bad actors pay no attention to U.S. engagement in the region is a blind spot for the Biden administration. As it sought normalization with Maduro, Ortega adjusted his playbook.

By contrast, Trump’s first term created a blueprint on how to effectively secure our border, address crises in the region by empowering allies, and combat narcotics trafficking and transnational criminal organizations with smart and strategic deployment of resources. Moreover, he knew how to effectively contain our foes, whether in Havana and Caracas, or Tehran and Beijing. We did it once and it can be done again. However, where progress was just gaining momentum after decades of abandonment, and where opportunities still abound, are in the investment and trade policies that can mutually grow the economies of the Americas.

Unfortunately, the contrarianism of the Biden administration has turned the fundamental tenets of América Crece into performance art, sacrificing regional allies and touting endless dialogue rather than strong policy actions that support economic growth. Bolstering U.S. economic ties through the Americas Partnership for Economic Prosperity is more about photo opportunities and speeches with little follow-through on U.S. investment. The Biden administration’s shift from prioritizing regional nearshoring to global friend-shoring has further ensured that the greatest beneficiaries of a post-COVID decoupling from China would become faraway countries like Vietnam, India and Thailand, rather than our southern neighbors in the Americas. As a result, the U.S. Congress has desperately sought a course correction through a comprehensive legislative framework with bipartisan support called the Americas Trade and Investment Act (Americas Act).

We need to get back on track with concrete initiatives, whether by resurrecting América Crece, or rebranding it under a new and updated rubric. Such policy priorities that could “Make the Americas Grow Again” should have three overarching tenets.

1. ENERGY IS OUR COMPARATIVE ADVANTAGE

In 2019, the U.S. became a net exporter of both refined petroleum products and crude oil. Eight years earlier, in 2011, the U.S. had become a net exporter of refined petroleum products alone. These developments gave the U.S. important leverage in its foreign policy and eliminated dependencies to countries as far as the Middle East and Russia, and as close as Venezuela.

Replacing Venezuela’s heavy and dirty crude with clean U.S. liquefied natural gas (LNG), and building the supporting infrastructure for its transport, storage, and conversion, was at the heart of the América Crece energy and infrastructure investment frameworks. Plus, it’s good for the environment. Clean natural gas is a major reason why the U.S. has reduced emissions more than any other nation in the world. Even green Europe recognizes natural gas as sustainable.

Despite this, not only did the Biden administration scrap América Crece, but it added insult to injury in January 2024 by pausing new U.S. Department of Energy approvals of proposed LNG export projects. Compounding this misstep, the U.S. Department of the Treasury previously published a guidance to oppose any projects at international financial institutions that directly or indirectly support the oil and gas industry. This (mis)guidance was infamously used by the Biden administration in 2021 to scrap project finance support for port and shore-base logistics facilities in Guyana, a U.S. ally that has become the fastest-growing economy in the world, and has recently surpassed Venezuela’s exports with the support of U.S. energy companies.

We need to get back on track with concrete initiatives, whether by resurrecting América Crece, or rebranding it under a new and updated rubric.

Ironically, while the Biden administration punishes U.S. ally Guyana for its hydrocarbon development, it has simultaneously rewarded the neighboring Maduro regime in Venezuela by easing sanctions on its state-owned oil company, Petróleos de Venezuela (PDVSA), losing valuable political leverage by making the Maduro regime believe—once again—that the U.S. needs its products.

While most (correctly) assume China is the biggest beneficiary of such missteps, another major winner has been Vladimir Putin’s Russia. Last year, Russia stunningly overtook the U.S. as Brazil’s largest supplier of fuel. Brazilian imports of Russian diesel soared 4,600%, while purchases of fuel oil rose by almost 400%, resulting in over $8.6 billion of de facto sanctions relief for Russia. If this has been the impact on the biggest economy in Latin America, which also happens to be a major oil producer and net exporter, imagine the susceptibility of smaller nations.

2. SMALL COUNTRIES PRESENT BIG OPPORTUNITIES

U.S. policymakers have generally had a hard time focusing on opportunities in Latin America and the Caribbean beyond the large countries of Argentina, Brazil and Mexico. Even when they are forced to think about the smaller countries, they tend to lump them into sub-regional groupings, so they can “matter” more together. The same logic exists among investors, perhaps as a direct consequence of policymakers, which has proven to be lazy and counterproductive.

Whether as a policymaker or investor, some of the best opportunities—for both policy and investment returns—are in the smaller countries of the region. Not only are they the fastest-growing economies—i.e., Guyana, Panama, Paraguay, Dominican Republic—but they are strategically located and present unique dynamics that further our national interests. These markets outpace regional neighbors because of higher-growth trajectories, while posing a lower relative investment risk than Argentina, Brazil and Mexico. However, they remain grossly undercapitalized and need to attract investors with opportunistic deals.

Pointedly, some of the early successes of América Crece were in smaller countries. In Panama, the investment program catalyzed over $2 billion in financing for energy projects that included gas to power, mini-grid portfolios, and a tender for a new transmission line; in El Salvador, over $1 billion was committed for the country’s first integrated LNG import terminal and gas power plant; and in Ecuador, the program secured $3.5 billion in a bridge financing facility focused on private capital solutions for state-owned enterprises.

On trade policy, similar to the successful termination and renegotiation of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) during Trump’s first term, the next trade agreement that needs to be terminated and reimagined altogether is the Central American Free Trade Agreement (CAFTA). This would serve two purposes: It would remove the unmerited U.S. market access that the Ortega dictatorship in Nicaragua currently receives, and it would allow us to focus on the comparative advantage and opportunities that each country in Central America presents, rather than the perpetual bunching and pigeon-holing that restrains their growth. After all, CAFTA’s narrowly defined manufacturing thread-lines did little to protect market access, as investors pivoted to China and Vietnam in pursuit of cheaper labor and production.

Fortunately, the Americas Act seeks to recreate the efforts that we began in the first Trump administration regarding nearshoring and reshoring, including financing and tax incentives, and a new approach that would expand access to the USMCA and the Caribbean Basin Trade Preference Area (CBTPA). It proposes a set of strict criteria to allow smaller countries to join a docking mechanism within the USMCA. Much of the chatter about this approach has focused on Costa Rica and Uruguay as early contenders. Unfortunately, while Costa Rica’s current leadership deserves great credit, the short-sightedness of a president, Laura Chinchilla, to pursue and enact the region’s second free trade agreement with China in 2010, may hamper Costa Rica’s compliance with the “non-market economies” clause in the USMCA. It’s a mistake recently replicated by Ecuadorian President Guillermo Lasso before leaving office in 2023, and which Uruguayan President Luis Lacalle Pou and his successor should seek to avoid.

The legislation further envisions the CBTPA as a temporary step until a country can meet the strict criteria for USMCA membership. This fallback provision can also become an attractive alternative for regional allies that don’t have trade agreements with the U.S., including Paraguay, which is one of the strongest allies in the region. It is also the only country in South America that diplomatically recognizes Taiwan, and that has resisted extraordinary pressure and extortion from China.

3. PRIORITIZE U.S. AGENCIES AND BILATERAL INITIATIVES

The Americas Act also envisions the creation of an Americas Investment Corporation (AIC), to provide preferential loans, equity, lines of credit, and insurance/reinsurance for investments that are consistent with U.S. foreign policy goals and interests in the region. It would be akin to a standalone U.S. Development Finance Corporation (DFC) for the Americas. Ultimately, if passed, a final structure could take various iterations, but most importantly, this bilateral approach is the way to go. It is a much better investment for U.S. taxpayers than any of the multilateral institutions, which lack speed, impact, transparency and accountability.

Think about it. Latin America and the Caribbean has at its behest: the largest regional multilateral development bank in the world (the Inter-American Development Bank, IDB); the largest subregional development bank in the world (the Development Bank of Latin America and the Caribbean, known as the CAF); plus three other peripheral subregional development banks: the Central American Development Bank (CABEI), the Caribbean Development Bank (CDB), and FONPLATA (the Southern Cone’s development bank). Add the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF), which have some of their largest overall portfolios in the region. Yet despite all of this multilateral largesse, unmatched anywhere else in the world, Latin America and the Caribbean lags far behind and has the largest gap in infrastructure finance in the world—at over $350 billion per year.

Some of the best opportunities—for both policy and investment returns—are in the smaller countries of the region.

Why? Because private capital, primarily in the form of U.S. investors, has been crowded out. Moreover, because these multi-country bureaucracies are inherently politicized, with perverse and misaligned incentives, outdated instruments and business cultures, and protectionist red tape, they have only succeeded at distressing assets throughout the hemisphere. At the cost of expanding U.S. investment in the region, countries continue to crutch on access to taxpayer-subsidized budget-support loans and long-tenor debt structures that do not contribute to improving investment climates or the expansion of strategic sectors.

Therefore, the U.S. Congress should focus its fiduciary duty to taxpayers on U.S. agencies, over which it has direct oversight and accountability. But simply increasing funding for a strengthened, more Americas-centric DFC, or creating a separate AIC, is not enough. It has to be accompanied by proactive civil servants who understand the strategic importance of their work to advance national security interests.

We need to develop a new vision that creates a mission-based agency with the know-how and expertise of investment banking that complements—not competes—with the good work of our development experts at the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID). To be successful, there can be no blurred roles or responsibilities. Further, the DFC must be strategic regarding its global footprint. Why open a DFC office in Brazil, the region’s largest economy and a G20 member? This reflects the persistent bias of agencies for low-hanging fruit, rather than opening the door to new, undercapitalized markets, where they can have an outsized impact.

The DFC (or a future AIC) needs to be proactive in developing pipelines and more agile in response to investment opportunities in newer markets. This will create additional opportunities and incentives that can crowd-in other investors. It is a stark contrast to what has become the norm for getting money out the door at the DFC: providing funds to local banks in the region for thematic lending—a practice straight out of the multilateral playbook. Ultimately, such instruments only de-risk wealthy Latin American bank owners, shower them with free money, create competitive disadvantages, discourage other investors and have negligible impact.

These U.S. agencies need to also be able to invest in all countries of the region—not remain limited by the World Bank’s criteria. Currently, the DFC is hamstrung in key countries such as Chile, Panama, Uruguay, Barbados and the Bahamas because they are labeled as “high-income.” Ironically, these are also the countries where China has made some of the most significant investments in strategic assets. The DFC should be able to pursue deals, based on U.S. foreign policy interests, in any U.S.-friendly country in the hemisphere. If the DFC’s name creates confusion, or its criteria can’t be updated, then let’s create an AIC that can make up for lost time and ground.

It’s beyond time for U.S. agencies, together with U.S. investors, to aggressively pursue the capital-intensive, high-quality deals that abound throughout the region, without any self-imposed hindrances, so that together we can Make the Americas Grow Again.

—

Claver-Carone is a Miami-based private-equity investor focused on energy and infrastructure in the Americas. He was a U.S. Treasury and National Security Council senior official in the Trump administration and president of the Inter-American Development Bank from 2020-22.