It is rare to see unedited and spontaneous portrayals of

But a thought-provoking art exhibition at Bogotá’s Museum of Modern Art (also known as Mambo) offers a unique and moving insight into

On display are oil paintings produced by 35 men and women who fought for different sides in

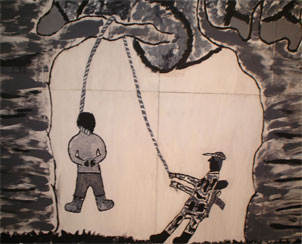

The paintings depict the horrors of Colombia’s war—hostages tied to trees, massacres, villages being attacked, mass graves, torture, people fleeing, and corpses floating in orangey-red rivers.

The project, the brainchild of Colombian artist Juan Manuel Echavarria, aims to reconstruct and preserve “a historical memory” of a nation at war and raise awareness, as the exhibition’s name (“The war we have not seen”) suggests.

Echavarria invited ex-fighters who had laid down their arms and government soldiers who had been injured in battle to take part in art workshops. Eighty demobilized fighters and government soldiers turned up to paint twice a week over the course of two years. Of the 420 paintings produced, 85 form part of the exhibition.

The adult ex-combatants were provided with unlimited oil paints and canvases and were encouraged simply to paint what they felt and what moved them most. Professional artists were on hand to show how to mix colors and offer basic painting tips.

The result is a raw and intimate account of the brutality of war as experienced by those on the frontline.

“It’s clear that these testimonies would not have been possible without the mediation of art,” said Ana Tiscornia, the exhibition’s curator.

The paintings—most of which are anonymous and have no title—are not censored, diluted or there to serve a political agenda. That’s what makes these works of art so special.

Their unedited experiences, seen often through child-like stick men and amateur brush strokes, capture

For the demobilized fighters and former government soldiers, the process of painting was a positive and cathartic experience. “It gave them a chance to get a lot off their chests,” said one workshop helper.

But the exhibition is much more than just a show case for the benefits of art therapy. The paintings are a stark reminder that rural violence continues in

Walking around the exhibition, it becomes immediately apparent that all the scenes of violence take place in

The paintings also highlight the cycle of violence that is so hard to break in

Several demobilized fighters who took part in the project have been murdered and a few have taken up arms again. But the majority has left the war behind for good.

“There are no lies here … what you see is reality,” said one museum guide. That’s what makes this exhibition a must-see.

It wraps up in Bogotá on the November 14, but Echavarria hopes to take the exhibition on tour across

*Anastasia Moloney is a contributing blogger to americasquarterly.org. She is a freelance journalist based in

Some of my photographs from the exhibit: