Porfirio Lobo will be Honduras’s next President. Consistent with recent polls, Lobo, the National Party candidate, won a resounding victory over Liberal Party candidate Elvin Santos. The results were unambiguous, and Santos quickly conceded victory while Lobo and the National Party celebrated their victory. This sharply contrasts with the 2005 elections, when doubts remained about the results for over a week and speculation about vote-rigging abounded. In 2009, conversely, the question is not who won, but how many people voted. The turnout question will now become the centerpiece of the debate on the election.

After rampant speculation regarding possible Election Day protests and violence, Sunday’s elections took place under relative tranquility. The military and police were out in full force on Sunday to protect the elections, and security concerns were high enough to warrant canceling flights from the United States. There was some reported repression of protesters in San Pedro Sula, raids on pro-Zelaya groups’ offices, and temporary jamming of pro-Zelaya media. Generally, however, Honduras was quiet, and those that opposed the elections stayed at home instead of risking arrest by protesting. By mid-afternoon, the capital was a ghost town, with political propaganda everywhere but virtually no one on the streets and few cars on the road.

Soon after the polls closed, the presidential results were clear. Porfirio Lobo won well over 50 percent of the vote, while Elvin Santos received less than 40 percent. This result was predictable. Though significantly more Hondurans self-identify as Liberals, the June coup and ensuing political crisis have deeply fractured the Liberal Party. Many Liberals who identified with the deposed president, Manuel Zelaya, vowed to stay away from the polls. As one Liberal Party poll worker in Tegucigalpa, Miriam DeVicente, explained on Sunday afternoon, once the polls were virtually empty, “I think that from the Liberal Party many people have stayed away.” Meanwhile, other voters punished the Liberal Party for the political crisis that took place on its watch.

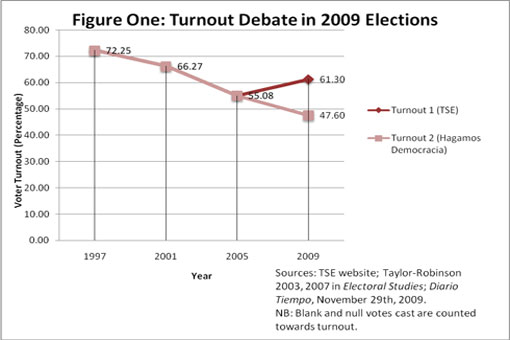

Despite the relative calm on Election Day and the clear presidential result, the debate on the election will continue this week. In particular, analysts from both de facto President Roberto Micheletti and deposed President Manuel Zelaya’s camps are focused on voter turnout. Before the polls had closed, Zelaya predicted voter turnout well below 50 percent (which would be the lowest since Honduras’s transition to democracy), while Micheletti’s side announced a “massive vote” that dwarfed the 2005 turnout rates. This debate remained unsettled on Sunday night, when the Supreme Electoral Tribunal (TSE) announced a preliminary voter turnout rate of 61.3 percent, while the nongovernmental observer group, Hagamos Democracia, announced an estimated turnout from its quick count at 47.6 percent.

Photograph courtesy of Daniel Altschuler

[To view more of my photographs of the election in Honduras, click here]

Hagamos Democracia’s report, which coincided with the TSE on who had won the election while differing substantially on voter turnout, raises questions about the electoral tribunal’s announcement. In particular, there is concern about the TSE’s incentive to inflate voter turnout rates to raise the perceived legitimacy of the elections. On Sunday night, the Tribunal got a standing ovation from national and international observers when it announced 61 percent turnout, because this figure implied that the elections’ legitimacy could not be questioned.

Members of the press, however, remained doubtful of this figure—because of the quick count result, their own impressions of very low turnout (particularly in poorer areas of Tegucigalpa) and delays in reporting the results. The TSE initially promised to present preliminary results by 7:00 pm, but they did not release them until 10:00 pm, at which point they announced “technical difficulties” with their communications network. This delay was not as big as in previous years, but it was long enough to sow doubts about what was going on behind the TSE’s closed doors.

Looking at voter turnout, if one accepts the TSE figure for 2009, then this election has turned the tide of declining voter participation in Honduras. Proponents of this argument have already argued that such turnout—in the face of protests and boycott threats—reflects the legitimacy of the elections and the fact that the vast majority of Hondurans want to move on from the Zelaya-Micheletti debacle. Hondurans spinning the election from this side see this result as a clear proxy vote against Manuel Zelaya.

Meanwhile, the Hagamos Democracia figure suggests that many eligible Hondurans stayed away from the polls. Zelaya’s supporters will use this figure to suggest that most Hondurans heeded Zelaya’s call for a boycott and were too scared of military and police repression to vote. From this perspective, the elections do not reflect the will of the people. Instead, the coup led to an increase in abstentionism, which would be consistent with a rise in the apathy or disgust of Honduran voters with the political establishment.

Because this debate is so susceptible to “spin” from both sides, the turnout question is precisely where Honduras’s elections most needed objective oversight for these Honduran elections. But, with the Organization of American States and Carter Center refusing to observe and the UN withdrawing its support, the vast majority of national and international observers were biased toward the Micheletti regime and eager to declare the elections a resounding success. For instance, the Washington Senior Observer Group—which included former member of Congress Jerry Weller and former ambassador to Honduras James Creagan—issued a press release congratulating Honduras on its elections well before any results had been released. Groups like this reported that those who did come to vote felt no intimidation or fear. Nor because of their limited numbers could these groups oversee the tallying beyond individual voting stations, and those were not a statistically valid sample. Their presence thus provided little help on the turnout question.

Through Monday, then, it is not clear how much scrutiny there has been of the counting process. Hondurans will continue to await the full election results—including the final tallies for mayors and congressional races, which take longer to tabulate but will shed more light on voting patterns—from the TSE. In addition to these official reports—which could be less reliable on turnout—one important group to follow will be the National Democratic Institute (NDI), which will release its report in the coming days.

The take-away from all this is that uncertainty prevails. Given the lack of violence and disruption on Election Day, it is hard to imagine the election results being overturned or discarded. But if subsequent reports that turnout was lower than the TSE initially announced are true, they risk the possibility of stoking the division within Honduran society. This suggests that Honduras’s political drama may not be over, and that the question of Manuel Zelaya’s restitution—and, more generally, of healing the wounds of this fragmented country—will remain a concern in the days and weeks to come. And with the Congress set to debate Zelaya’s restitution on Wednesday, the next critical moment in this story may take place before the turnout debate has been settled.

*Daniel Altschuler is a contributing blogger to americasquarterly.org conducting research in Tegucigalpa, Honduras. He is a Rhodes Scholar and doctoral candidate in Politics at the University of Oxford, and his research focuses on civic and political participation in Honduras and Guatemala.