When I hear people talk about troubled areas of Central America, using terms like “hopeless” and “failed state,” it reminds me of what many said about Colombia in the 1990s and early 2000s. During that terrible era, drug cartels and guerrilla groups were so powerful – and the Colombian government so weak – that criminals bombed churches and nightclubs, hijacked airplanes and kidnapped presidential candidates, senators and thousands of other people per year. Many Colombians and outsiders alike believed progress was simply impossible.

Looking back, if one tries to extrapolate lessons for Central America’s future… well, there’s good news and bad.

The good news is that progress was in fact possible – to an amazing extent. During the 2000s, kidnappings plummeted from more than 3,500 a year to about 280. Foreign investment doubled, and exports tripled. The murder rate fell by half. The biggest guerrilla force, the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia or FARC, saw its fighting force fall from 30,000 to 6,800 – setting the stage for peace talks today.

The bad news? Making all that progress was really, really difficult. Because it wasn’t simply a question of building up the military or implementing a “mano dura” approach to policing. Rather, it required a convergence of superb leadership, political consensus from the Colombian people and sustained support from the international community. Perhaps the most important (and forgotten) aspect: an emphasis on fixing social and economic problems as much as security challenges.

The new issue of Americas Quarterly looks at Central America’s so-called Northern Triangle of Guatemala, El Salvador and Honduras and asks: What would it take for a similar turnaround to occur there? All three countries are among the world’s most violent – indeed, the only place deadlier than El Salvador last year was Syria. Stagnant economies and insufficient job creation have contributed to a tide of refugees. To be sure, there has been some progress in all three countries, including the investigation and removal of an allegedly corrupt president in Guatemala in 2015 and signs of strengthening democracies elsewhere. But the road ahead will require a variety of strategies – some of them obvious, some of them creative – for there to be progress on anything resembling a Colombian scale.

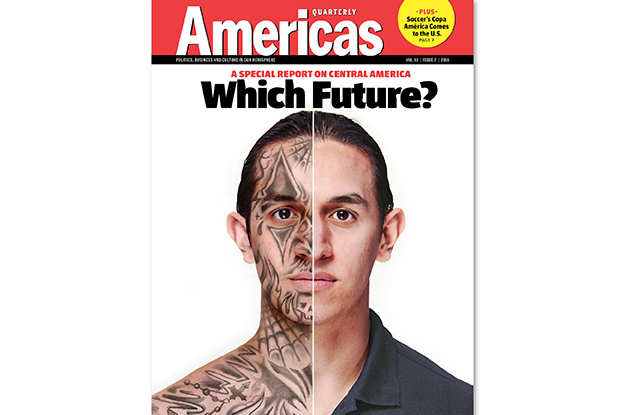

Carolina Ávalos, a Salvadoran economist, writes about how women’s rights are a necessary step to better education and lower violence. Salvador Paiz and Robert Muggah look at how changes in U.S drug policy may be necessary for violence in the region to meaningfully decline. Indeed, the United States is a source of many of the Northern Triangle’s problems – from demand for cocaine to the gang culture referenced on this issue’s cover. Victor Umaña looks at how the $750 million aid package from the United States, which attempts to address some of those ills, can be more wisely spent.

This issue’s centerpiece is the cover story by Richard Lapper, a distinguished journalist who began his career covering Central America’s wars of the 1980s. Richard returned for AQ to see how the region has changed – and spent one week in each of the Triangle countries, interviewing business leaders, politicians and everyday people. He identified promising success stories in agriculture and education that provide hope. But Richard concludes that little else will matter unless the security situation is addressed, and cites Álvaro Uribe, Colombia’s president from 2002 to 2010, as an example to follow. (To read Lapper’s piece in Spanish, click here.)

Uribe’s legacy has been complicated by the human rights violations that occurred under his watch, as well as his public falling-out with his successor, Juan Manuel Santos. Yet aspects of his story do provide a useful roadmap – because they show how economic, social and security policy must be intertwined together to produce results.

For example, one of Uribe’s most important early accomplishments was to convince Colombia’s wealthiest 1 percent to pay a special “Democratic Security Tax,” a levy on net assets. This ultimately funded 100,000 additional soldiers, swelling the armed forces by about a third and allowing the government to expand its reach to previously neglected areas. Convincing Guatemalan, Honduran and Salvadoran elites to do something similar will require politicians to win their confidence, and convince them the money won’t be siphoned away by corruption. But some increase in revenues will surely be necessary, since Northern Triangle countries on average collect just 13.6 percent of their gross domestic product in taxes – compared to a 24.4 percent average for Latin America’s largest economies.

The increase in tax revenue, plus a growing economy, allowed Uribe’s government to boost social spending by 85 percent during his eight years in power – even more than the 65 percent increase in defense spending. Other Latin American presidents who have tried to follow Uribe’s path, such as Mexico’s Felipe Calderón, have probably focused too much on the military side of the equation. But emphasizing the economy and innovative social policies give citizens an additional and arguably more compelling reason to buy into the often difficult sacrifices needed on the security front. If the Northern Triangle’s leaders can achieve that balance, then any future is possible.

—

Winter is the editor-in-chief of AQ.