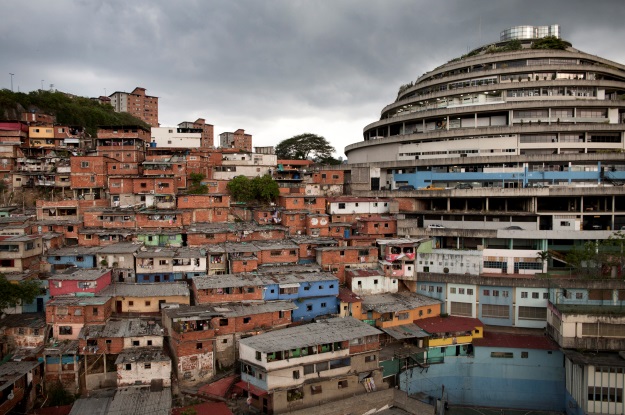

There is perhaps no more poignant physical symbol of Venezuela’s decline – its authoritarian turn, flattened opposition, and imminent risk of default and economic catastrophe – than the huge concrete spiral known as El Helicoide, in central Caracas.

Once planned as South America’s most spectacular monument to modern capitalism, El Helicoide is today Venezuela’s most notorious torture center: Since protests rocked Caracas in 2014 and earlier this year, over three hundred students, activists and politicians have been crammed into its cells. Inside, Venezuelan police forces, in particular the SEBIN (intelligence and counter-intelligence) and the PNB (national police), reign supreme.

But the hidden history of El Helicoide lies not only in the tragic present of its prisoners, but in the six decades of social oblivion and urban misery in which thousands of families have lived since the building’s construction began.

Built between 1956 and 1961, El Helicoide would have been the largest, most state-of-the-art mall in the Americas, as its stellar appearances in MoMA’s 1961 Roads exhibition and major international magazines clearly attest. At a cost of $10 million (equivalent to $90 million today), the Brutalist-style building was conceived as a gigantic showroom for the country’s emerging oil and mineral industries, as well as a hub for commerce and entertainment.

Composed of two interlocking spirals with two-and-a-half miles of vehicular ramps, the massive structure would have housed 300 upscale stores, eight cinemas, a heliport, and a hotel, all serviced by custom-made Austrian elevators. Unused, these eventually rotted in their cases. A geodesic dome, inspired by Buckminster Fuller’s famous blueprint, also spent 20 years in storage before being installed.

There is no shortage of helicoidal ironies: even as its famous models were showcased across the globe, the construction site in Caracas ground to a halt. After the fall of dictator Marcos Pérez Jiménez (1952-1958), the building’s architects (Jorge Romero Gutiérrez, Pedro Neuberger and Dirk Bornhorst) were suspected of an undue alliance with the military regime. Though unproven, this assumption led the incoming democratic government to curtail the necessary credits to finish the structure. Litigation and bankruptcy ensued and El Helicoide was paralyzed one year short of completion.

The neighborhoods surrounding El Helicoide, namely those of San Agustín del Sur, were always implicitly part of the project’s mission. Like many others, this community started as a cluster of caseríos, rural shacks raised by migrating populations attracted to the capital city. These communities densified massively following the discovery of oil and the radical modernization of Caracas starting in the late 1930s.

One of several “cities within a city” (along with the Universidad Central de Venezuela and the Centro Simón Bolívar), El Helicoide was included in the urban planning of mid-century Caracas, which stigmatized poor communities as signs of “backwardness.” Not only did El Helicoide’s construction benefit from the broad-ranging, state-run projects that led to the demolition of such ad hoc housing, but the building itself was to cap a reforestation plan that entailed razing the shantytowns in the surrounding hills.

Shantytowns are hard to tear down, though. They house several generations and cover the city’s far east, west and south-western areas, constituting over half of Caracas’ built environment. They also provide a cheap workforce of domestic, construction and even office services for less than minimum wage. So, while the “formal” city may want its barrios out of sight, Caracas could not function without their inhabitants, who service a society that has long viewed consumption as progress and capitalism as democracy.

At the close of the 20th century, Hugo Chávez was elected on promises to tackle the social disparities that kept 80 percent of Venezuelans below the poverty line. Had his self-styled Bolivarian Revolution delivered on these promises, poor communities nationwide, including the ones around El Helicoide, would have had clean water, closed sewage, legal electricity, garbage collection, reliable health and education services, sports and cultural facilities, and better access to employment.

Instead, San Agustín del Sur is considered one of the most dangerous shantytowns in Caracas. Its residents have mixed feelings about the spiral jail that sits in their midst. Some of them recall playing as children in the abandoned structure, using it as refuge during the 1967 earthquake, or helping landslide victims who were among the nearly 10,000 people who inhabited the building from 1979 to 1982, in an event known as “the great occupation.”

This relative cohabitation of the neighboring communities with El Helicoide ended in 1985, when the intelligence police was granted a 15-year lease for the building’s two lower levels, where the prisoner’s cells are currently located. Strategically situated, the building gave officers easy access to the nearby Central University of Venezuela (UCV), a hotbed of political protests, and to the military barracks of Fuerte Tiuna. The barrios served as a shield behind which the police could withdraw, further isolating the structure.

As each successive government mooted its own grand reinvention plan for El Helicoide, none – Chávez and Nicolás Maduro included – ever thought of how the site might service the neighboring communities.

As its cells fill up to unprecedented levels, many community residents pretend to ignore this huge gray elephant in their midst, claiming “that thing doesn’t exist for us.” Maybe when “that thing” is cleared of prisoners and is made useful to its surrounding barrios, El Helicoide will attain, if not the luster it never achieved, at least a purpose to redeem the unfortunate site of its many tragedies.

—

Olalquiaga and Blackmore are authors of the forthcoming book, Downward Spiral: El Helicoide’s Descent From Mall to Prison.