Reducing Homicide

What Presidents Are Doing

AQ examines how the region’s leaders are tackling homicides por Emilie Sweigart

The murder epidemic in Latin America is an appalling tragedy. But it is also an incredibly complex public policy challenge stemming from problems that have plagued the region for decades: drug trafficking, organized crime, contraband, illegal mining, land rights, and in some cases, violence by state security forces themselves. AQ looks at the wide range of policies presidents have implemented (and presidents-elect are proposing) to protect the lives of their citizens.

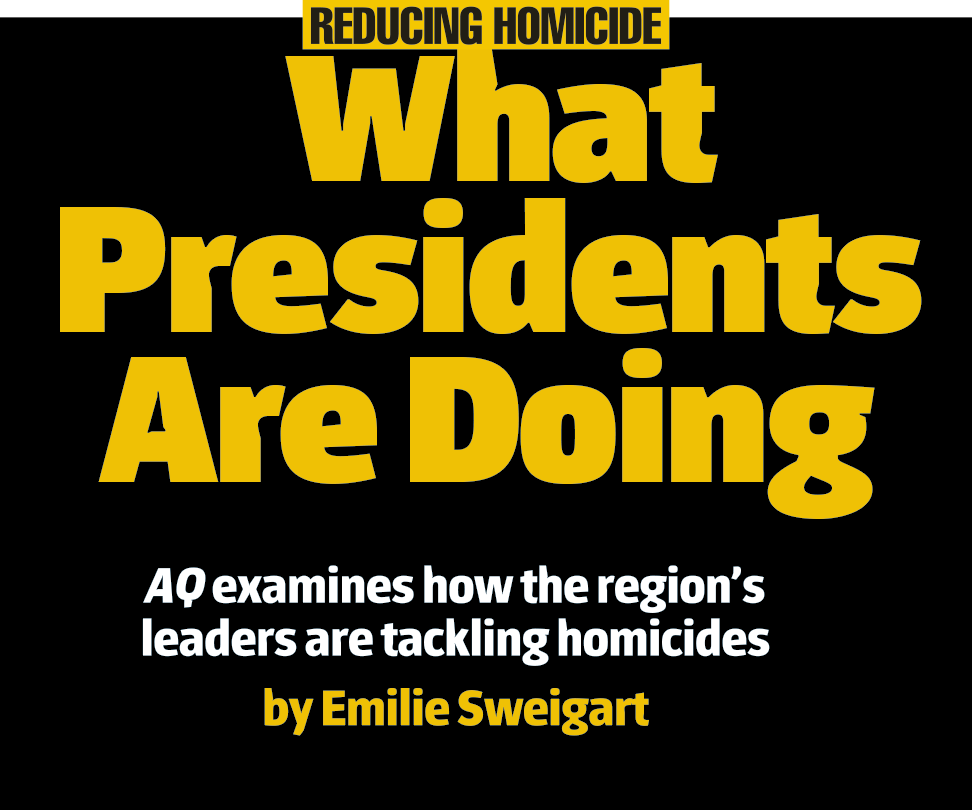

NOTE: DATA ARE FROM 2017 EXCEPT FOR ARGENTINA, BOLIVIA, BRAZIL, CHILE, DOMINICAN REPUBLIC, PANAMA, PERU, AND URUGUAY FIGURES, WHICH ARE FROM 2016

Guatemala | Honduras | Mexico | Nicaragua | Panama | Paraguay | Peru | Uruguay | Venezuela

What’s happening

The national murder rate decreased 13 percent between 2016 and 2017, according to government statistics. But trouble spots remain: Buenos Aires province accounts for almost 45 percent of the country’s killings (despite having only a third of its population), while gang wars in the port city and key drug transit point of Rosario made Santa Fe province the country’s most murderous: 10.7 homicides per 100,000 people.

What Macri is doing

Macri has said criminal impunity represents one of “the greatest shortcomings of 30 years of Argentine democracy.” Soon after taking office, he declared a public safety emergency, enforcing stricter border controls and authorizing forces to shoot down planes suspected of transporting drugs if they ignore orders to land. Macri implemented the Safe Neighborhoods program, deploying military forces alongside police in violent sectors of Buenos Aires and Santa Fe, and pushed for government transparency on drug consumption and crime victimization rates.

What critics say

Military intervention in domestic security breaks a post-dictatorship consensus to limit the role of the armed forces, said Paula Litvachky of the human rights group Centro de Estudios Legales y Sociales. Macri and Defense Minister Patricia Bullrich have praised police officer Luis Chocobar, who fatally shot a man in the back attempting to rob a tourist in Buenos Aires. Critics say their support is an endorsement of the excessive use of force.

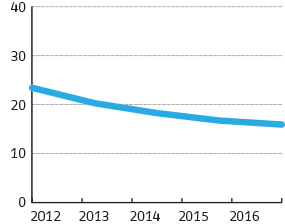

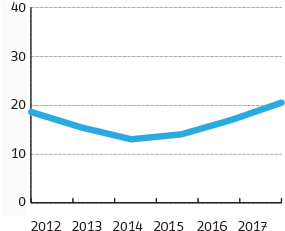

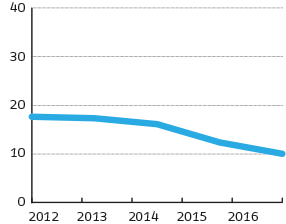

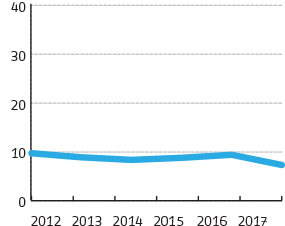

What’s happening

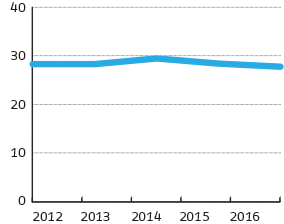

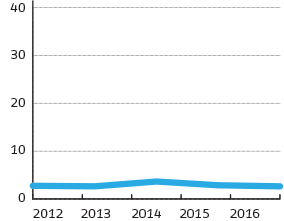

The already low homicide rate dropped by a third from 2012 to 2016, but drug trafficking continues to vex authorities. Despite government efforts to promote legal uses of coca, Bolivia remains the world’s third-largest cocaine producer, and 60 members of the Bolivian police were investigated for involvement in the narcotics trade in 2015. The department of La Paz’s murder rate is 10.7 per 100,000, by far the country’s highest.

What Morales is doing

Morales approved a law to expand legal coca farming in 2017 after cracking down on cocaine production the year before by signing agreements with neighboring countries to control crossborder drug flows. Also in 2016, he announced BOL-110, a $105 million project upgrading law enforcement technology (110 is the police emergency number). Funded by a state-owned Chinese company, it will modernize the police force with drones, facial recognition systems and modern emergency call centers.

What critics say

The Morales administration’s investment in technology has not been a major factor in reducing homicides, according to Bolivian security expert Gabriela Reyes Rodas. She points to a lack of trustworthy government data and mechanisms to evaluate police performance. Human Rights Watch warns that public safety laws passed in the Morales era have led to longer sentences and prison overcrowding.

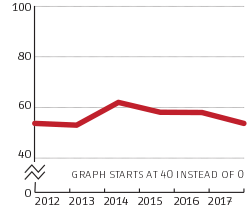

What’s happening

Though only 3 percent of the world’s population lives in Brazil, 14 percent of its murder victims die there. In 2017, that meant 59,103 lives lost. The unsolved assassination of Rio de Janeiro Councilwoman Marielle Franco in March, carried out with ammunition originally purchased by the federal police, brought increased international attention to the crisis. High polling numbers for right-wing presidential candidate Jair Bolsonaro signal that many Brazilians are ready for a hardline approach.

What Temer is doing

Temer has called the rampant violence a “national public safety emergency,” and in early 2017 launched a National Security Plan. In February, Temer signed a controversial decree calling in the military to bolster security in Rio de Janeiro state and created a Ministry of Public Safety to coordinate federal law enforcement efforts. In June, he diverted $250 million from the Ministries of Sport and Culture to the new department.

What critics say

Temer is extremely unpopular, so critics abound. His deployment of the military in Rio was a politically motivated decision that could lead to human rights violations, said Robert Muggah of the Igarapé Institute, a Rio-based think tank. Security experts have called the intervention a short-term solution to a longstanding problem, but it was widely popular among the public. The press has noted that much of Temer’s National Security Plan has not left the drawing board.

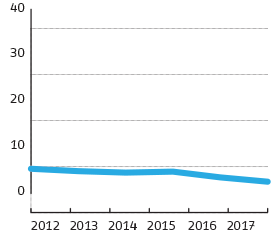

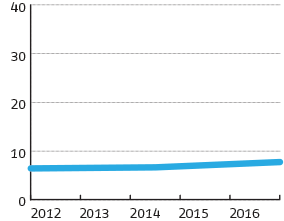

What’s happening

Despite its low murder rate, crime tops national opinion polls as Chileans’ biggest concern. Perceptions of crime can create intense political pressure, according to Nathalie Alvarado, a security expert at the Inter-American Development Bank. Though the public’s trust in the carabineros (the national police) has historically been high, 28 percent of Chilean households were victims of crime in 2018, up from 24.3 percent in 2012. Drug trafficking is also on the rise as the country’s ports become increasingly important transit points for cocaine.

What Piñera is doing

Security featured heavily in Piñera’s 2017 campaign as he promised to overhaul and modernize the carabineros, incorporate new technologies and tighten border security. As president, he launched a program that requires police to publish crime statistics every 30 days and rolled out a crime prevention system that analyzes citizen crime reports. Amid a recent influx of Haitian and Venezuelan immigrants, Piñera has tightened visa restrictions after linking immigrants to crime during his campaign.

What critics say

Alejandro Guillier, Piñera’s leftist opponent in the recent election, criticized the president’s anti-immigrant comments in 2016, noting that only 2.37 percent of people imprisoned in Chile are foreigners. Mahmud Aleuy, a Socialist Party member, called Piñera’s comments on immigrants and crime xenophobic, racist and irresponsible.

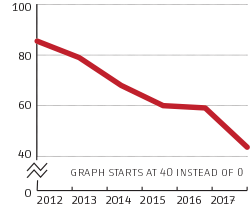

What’s happening

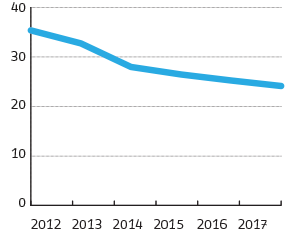

Colombia’s homicide rate plunged starting in 2002. After a brief plateau, it started to decline again around when peace talks with the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) began in 2012, reaching a 42-year low in 2017. Violence by FARC dissidents and National Liberation Army (ELN) guerrillas caused an upward blip, however, in the first quarter of 2018, when homicides rose 11 percent year-on-year. The groups are fighting for control over lands abandoned by the demobilized FARC amid record levels of coca production.

What Duque is promising

Duque, an ally of former President Álvaro Uribe, takes office on August 7. He has committed to strengthening police forces in cities by investing in intelligence and creating a monitoring system for civilians to help authorities georeference crimes. He has voiced opposition to aspects of the FARC peace agreement and government negotiations with the ELN, promising to modify the accord to allow prosecution of former militants for drug offenses.

What critics say

Given Uribe’s strong opposition to the FARC peace agreement, warned Adam Isacson of the Washington Office on Latin America, Duque might undo key aspects of the deal and jeopardize fragile security gains. Gustavo Petro, who lost to Duque in the 2018 presidential runoff, accused the president-elect and his party of promoting a return to war and exploiting fear as a campaign strategy.

What’s happening

Gangs are on the rise in Costa Rica: Murders tied to organized crime rose from 2.5 percent of total homicides in 2010 to 46.2 percent in 2016, driving total numbers up to a record high of 603 in 2017. Over half of the country’s homicides are connected to drug trafficking, almost half of which occur in the capital and surrounding San José province.

What Alvarado is doing

Alvarado took office in May. During the campaign he proposed stricter control and monitoring of firearms, and scanners at customs checkpoints to stymie contraband and drug trafficking. In his first speech as president he pledged to fight the social roots of crime with preventive policies, reintegrate prisoners into society to reduce prison overcrowding, and act “with rigor against violent crimes.” He has since signed a law creating a national police academy to improve training for the country’s 13,000-strong police force.

What critics say

Opposition politicians have registered concerns over a lack of funds for the country’s planned investments in crime-fighting vehicles, infrastructure and scanners. Alvarado’s security minister, Michael Soto, has acknowledged his ministry’s $9.6 million budget deficit, characterizing Costa Rica’s security situation as “gray and sad.” Soto has stated that that he will seek donations and public-private partnerships to finance the ministry’s needs.

What’s happening

The Dominican Republic is a drug-trafficking hub, the final Latin American stop for Colombian-grown cocaine arriving from Venezuela en route to the U.S. and Europe. A poll shows that 74.6 percent of Dominicans cite crime as their main concern; 72.8 percent have little or no trust in the police, who, according to the country’s National Commission on Human Rights, were responsible for around 200 extrajudicial killings in 2016. That’s equivalent to one-eighth of the country’s homicides.

What Medina is doing

In his first term, he introduced a presidential commission to reform the national police, launched an emergency response and video surveillance system called Sistema 911, and created the Peaceful City Joint Task Force, which deployed soldiers to patrol alongside police officers in high-crime areas. In his second term, he has expanded Sistema 911 and introduced georeferencing to pinpoint crimes and create a criminal database.

What critics say

Allegations of corruption have drowned out other criticism of Medina, but his militarization of patrols in violent areas was called reactive and indiscriminate by security expert Daniel Pou. Instead of placing the military on the streets, critics believe Medina should enforce stronger crime prevention policies. The country has other untended security challenges, including drug trafficking and contraband along the border with Haiti, compounding already delicate migration issues.

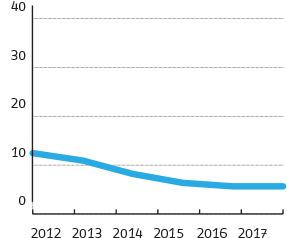

What’s happening

Though homicide rates have declined since 2010, murders are concentrated in Quito and the port city of Guayaquil, the country’s largest metropolis and a major South American cocaine hub. Despite low absolute numbers, the provinces neighboring Colombia have some of the country’s highest homicide rates, and are plagued by criminal groups vying for control in the vacuum left by the FARC’s demobilization. The region is also a hotspot for human trafficking and movement of contraband gasoline and drugs.

What Moreno is doing

On March 2, the president announced a $950 million plan to improve infrastructure and services for security forces and continued expansion of the successful community police, with 100 new stations. Later that month he announced he would send 12,000 troops to the Colombian border to address violence in Esmeraldas province, where a dissident FARC faction had set off a car bomb outside a police station and kidnapped and murdered Ecuadorean journalists and soldiers.

What critics say

Moreno has been criticized for negotiating with the dissident FARC leader after the journalists’ kidnapping, and for straining peace talks between the ELN and the Colombian government by ending Ecuador’s mediation role in the negotiations. Security experts also blame the previous administration, in which Moreno served as Rafael Correa’s vice president, for failing to establish a significant enough military or police presence on the northern border.

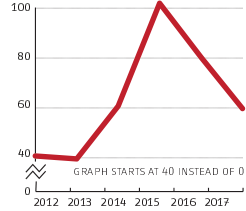

What’s happening

Ninety-five percent of El Salvador’s murders go unsolved, but it is widely believed that gangs are responsible for the vast majority. The country’s estimated 60,000 active gang members outnumber the combined forces of the police and military. In 2012, the government brokered a truce between the country’s two main gangs, MS-13 and Barrio 18, but it was short-lived. A 2015 Supreme Court ruling classifying MS-13 and Barrio 18 as terrorist organizations lengthened maximum sentences for gang members.

What Sánchez Cerén is doing

Sánchez Cerén has implemented a mano dura approach to organized crime. In 2015, he launched the $200 million a year Safe El Salvador Plan, a crime prevention program for the country’s 50 largest municipalities that saw homicides fall but led to allegations of police brutality and extrajudicial executions. In 2016 the president created a 1,000-strong Special Reactionary Forces group combining elite police units and military commandos.

What critics say

Human rights activists have denounced the clandestine jails and extrajudicial killings operated by security forces in recent years. El Salvador’s citizens face repression from both gangs and security forces, said Jeannette Aguilar, director of the University Public Opinion Institute at the Universidad Centroamericana. According to Aguilar, the country is fighting a low-intensity war in which the Salvadoran state is losing the battle against gangs and organized crime.

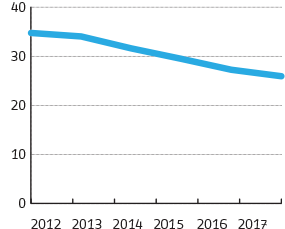

What’s happening

In February, Guatemala’s homicide rate fell to 25 murders per 100,000, the lowest since 2000 and a 49 percent drop from its 2009 peak. Murders are highly concentrated along Guatemala’s borders with Mexico, Honduras and El Salvador, largely as a result of drug trafficking and contraband activity, and Guatemala City, whose department accounts for 21 percent of the country’s population but 38 percent of its homicides.

What Morales is doing

Nearly two decades of controversial military involvement in urban law enforcement ended in April when Morales transferred the last of troops that once patrolled city streets to Guatemala’s borders in an effort to clamp down on drug trafficking. Domestic security responsibilities returned to the national police, whose ranks he increased by 8,000 this year. To combat gang activity in prisons, the Interior Ministry conducted a series of raids starting in January, confiscating weapons and cell phones.

What critics say

The president’s decision to appoint Enrique Degenhart as interior minister “was a huge mistake,” said Carlos Mendoza, a security expert and co-founder of Diálogos, a Guatemalan public policy organization. Degenhart has attempted to classify gangs as terrorist organizations and fired the head of the national police, under whose watch homicides had decreased.

What’s happening

Despite a recent downward trend, Honduras still has the fourth-highest murder rate in the world. Violence is concentrated in the north and northeast of the country, especially in the city of San Pedro Sula, which, with under 7 percent of the country’s population accounts for 16 percent of all murders. Gangs are concentrated in San Pedro Sula and the country’s other two major cities, La Ceiba and the capital, Tegucigalpa.

What Hernández is doing

In April 2016, the president announced a purge of the national police to remove corrupt officials; the government has since fired over 5,000 officers. Hernández also increased the national budget for security institutions, introduced a state intelligence system, and reinforced training for police investigators and anti-narcotics units. Hernández has aggressively targeted organized crime, and in May announced a new task force aimed at transnational maras and domestic gangs.

What critics say

Corruption is still clearly a problem within the Honduran police. In January, the Associated Press obtained a confidential report accusing the newly appointed national police chief of having assisted a cartel leader with a 1,700-pound shipment of cocaine in 2013. He denied the charges. The military police often take iron-fisted approaches to community-level crime and violence, which “continue to drive a wedge between residents of these communities and law enforcement,” said Eric Olson of the Wilson Center’s Latin American Program.

What’s happening

Mexico’s murder rate is the highest in two decades, with organized crime accounting for about three-quarters of the murders. Impunity is rampant: Between 2010 and 2016, 94.8 percent of murders went unpunished. The outgoing administration’s strategy of targeting the leaders of criminal organizations has fractured those groups into smaller, clashing entities. Public safety has been increasingly militarized: The December 2017 Internal Security Law authorized the military to intervene in domestic security matters.

What he is promising

Andrés Manuel López Obrador (AMLO) takes office on December 1. He has committed to reducing violence by relaunching the Public Safety Secretariat, which was eliminated in 2013, and by creating a national guard jointly staffed by the army and the navy. He has criticized mano dura security policies, stating that he would not “fight violence with violence” or use coercive measures to ameliorate public safety. AMLO also proposed granting amnesty for members of criminal groups to bring peace to the country.

What critics say

AMLO’s amnesty proposal has met with controversy—his opponents say his policy promotes impunity, which he denies, and disregards the constitution. Amnesty is a poor negotiation tactic that sacrifices justice in the name of peace, according to security analyst Alejandro Hope. In response, AMLO’s security policy advisor, Alfonso Durazo, stated that AMLO is not suggesting a pact with organized crime, but a solution backed by popular consensus and congressional approval.

What’s happening

Nicaragua’s homicide rate had been slowly decreasing since 2011, likely the result of innovative crime prevention programs and community policing. But homicides have spiked since April, after protests set off by the government’s announcement of austerity reforms erupted and were met with an unexpectedly violent reaction from security forces. Clashes have led to the deaths of at least 200 people through June.

What Ortega is doing

Ortega has prioritized modernizing the army. Since 2009, Nicaragua has received $26.5 million in military aid from Russia for weapons and armored vehicles. The president has also strengthened the national police — a 2014 law gave Ortega sweeping powers over the force, signaling his autocratic tendencies. Amnesty International documented his administration’s use of the national police, riot police and pro-government armed groups to carry out the attacks on protestors.

What critics say

Opposition politicians, former Ortega allies, the private sector and the Catholic Church have all spoken out against the recent violence. The Nicaraguan state must “immediately end arbitrary attacks on the lives and personal integrity of all Nicaraguans, with no distinctions whatsoever, including their political views,” according to Commissioner Antonia Urrejola, the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights’ rapporteur for Nicaragua.

What’s happening

Panama’s murder rate fell to a 13-year low in 2017, although a survey that year found that 82 percent of Panamanians feel unsafe, compared to 70 percent in 2016. The presence of more than 200 gangs has heightened security concerns. Gang activity is concentrated in the provinces of Panamá (including the capital), Colón (home to a major port) and Chiriquí. Panama’s isolated border with Colombia has made the area a haven for contraband and drug trafficking.

What Varela is doing

The president has said that 70 percent of homicides are related to drug trafficking and organized crime. He has prioritized dismantling gangs, launching the Safe Neighborhoods program in 2014. The amnesty and job training program for gang members did not achieve its violence reduction goals, leading Varela to a more militarized approach. In March 2017, he introduced a 300-strong security unit aimed at taking down gangs in Panama City and Colón.

What critics say

Varela’s security policies are reactive, rather than preventive, according to Severino Mejía, a criminologist and a former deputy minister of government and justice. Mejía has noted that while homicides have decreased, crime rates in other categories, including theft and domestic violence, have gone up.

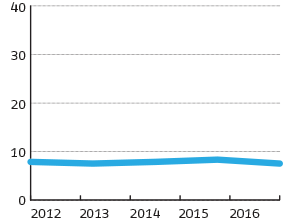

What’s happening

Although homicides and overall crime levels have decreased, two groups continue to wreak havoc: the Paraguayan People’s Army (EPP) and the Brazilian gang First Command of the Capital (PCC). Gang violence and arms trafficking are common along the Brazilian border, where the PCC operates. The EPP, a guerrilla group, has kidnapped 10 people and killed 43 in Paraguay’s northeast between August 2013 and January 2018. It has also been linked to drug trafficking.

What Abdo Benítez is promising

The president-elect, a former air force reservist who will take office on August 15, has accused the current administration of squandering resources and has promised to overhaul Paraguay’s security policy. He wants to improve border security, modernize the police and step up the fight against drug traffickers. Abdo Benítez has said he will combat the EPP by requesting regional cooperation and personally monitoring the task force assigned to fight the guerrilla group.

What critics say

Abdo Benítez’s ties to former dictator Alfredo Stroessner have caused concern that he will not respect human rights—his father was Stroessner’s private secretary and part of his inner circle. On the campaign trail, Abdo Benítez lauded the Stroessner regime’s contributions to infrastructure but attempted to distance himself from the legacy of state terrorism and political repression.

What’s happening

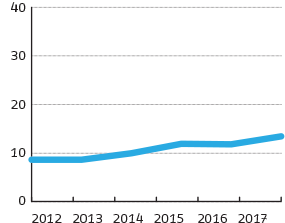

Public opinion polls reflect the strain of Peru’s rising homicide rate — 30 percent of Peruvians say security is their country’s most serious problem. Two border departments have murder rates many times the national average: tiny Tumbes on the Ecuadorean border, where organized crime groups run smuggling operations; and Madre de Dios, rife with illegal mining activity along the borders of Bolivia and Brazil.

What Vizcarra is doing

Vizcarra became president following Pedro Pablo Kuczynski’s resignation in March, but as this issue went to press he had yet to announce a security strategy. Vizcarra’s Interior Minister Mauro Medina has pledged continuity of policies pursued during the Kuczynski administration, including two programs focused on urban crime and massive operations against organized criminal groups.

What critics say

Vizcarra did not list security as a priority either in his first address to the nation or as one of the “five pillars” of his government’s four-year plan. This “worries” former Deputy Interior Minister Rubén Vargas, who has stated that he fears the president will focus on anti-corruption efforts at the expense of security. (It was a bribery scandal involving Kuczynski that elevated Vizcarra to the presidency. Within a month he created a new public integrity office.)

What’s happening

Uruguay’s homicide rate suddenly spiked this year: Killings from January to April rose 81.5 percent compared to the same period in 2017, from 81 to 147 murders. Robberies are also up sharply. The capital, Montevideo, is historically the most violent city, and crime has now spread to border areas. The country has become a transit point for the South American narcotics trade, which accounts for much of the violence along the border with Brazil.

What Vázquez is doing

In 2016, Vázquez launched a crime prevention effort in Montevideo. The program, which identifies hotspots and distributes police forces accordingly, has since expanded to nine of Uruguay’s 19 departments. In May, Vázquez created a presidential commission to centralize crime statistics and coordinate strategies on gangs and drug trafficking. He also announced plans to send 500 additional police to the northern department of Salto.

What critics say

Following the recent surge in homicides, Police Chief Mario Layera blamed the government for compartmentalizing information within departments and warned that Uruguay could soon reach crime levels like those of troubled El Salvador and Guatemala. As a result, some opposition leaders demanded the resignation of Interior Minister Eduardo Bonomi and police officials. Opposition Senator Jorge Larrañaga has called for a greater military role in policing and harsher sentencing.

What’s happening

Caracas is the world’s most violent capital, but homicide in Venezuela is widespread: Ciudad Guayana, Maturín, Valencia and Barquisimeto also have some of the world’s highest murder rates. Bolívar state has seen frequent lethal confrontations between the military and illegal gold miners, and both pro- and anti-government protests have led to deaths across the country. In March, the attorney general’s office reported that security forces had been responsible for 505 extrajudicial killings since July 2015.

What Maduro is doing

Maduro has launched multiple initiatives to expand the military’s role in reducing violence, with little success. His national security strategy includes plans to train 10,000 new members of the Bolivarian National Police (PNB) and 10,000 more national guard troops in coming years. Maduro has also introduced a program to arm civilians and instruct them to gather intelligence.

What critics say

Maduro has been roundly denounced for failing to address the killings as his government has become increasingly authoritarian. The police, military and colectivos — pro-government armed civilian groups — have incited violence during opposition protests, said Rafael Uzcátegui, director of the human rights group Provea. Outgoing Colombian President Juan Manuel Santos has accused Maduro of using criminal groups to act alongside security forces to control Venezuela’s population.