This article is part of “Connecting the Americas,” a collaborative project of Americas Quarterly and Zócalo Public Square.

XAPURI, BRAZIL

Entry into the Casa Chico Mendes Museum is free, but it’ll cost you $20,000 to visit the environmental activist’s assassin. He lives down the street—if you’re interested.

I was. I recently visited Brazil’s dusty Wild West town of Xapuri to look into the legacy of Francisco “Chico” Mendes, most famous defender of the Amazon rainforest and an inspiration to a generation of environmentalists—most notably Marina Silva, who may be the next president. How Brazil treated the memory Mendes—and his assassins, who have brazenly returned to their nearby ranch like characters from an old cowboy film—might provide a glimpse into the nation’s concern for environmentalism and activism, and maybe also into the candidacy of Silva.

In the 1980s, Mendes had rallied rubber tappers and Indigenous people in the Amazon to forcefully resist the encroachment of farmers and cattle ranchers, who were clearing a football field-sized swath of forest every second and spewing carbon dioxide pollution into the atmosphere. Mendes is an official national hero and a world-recognized activist, so I thought it was reasonable to also expect him to be revered in Xapuri.

“Chico Mendes has been a symbolic force for people all over the world,” the international environmental advocate Casey Box told me. “Other nations see him as a major force against industries and pushing back against aggression. He’s had a global reach.”

But in Xapuri itself, I couldn’t even find a postcard of Mendes for sale. While Box said he recalled seeing an Indigenous activist in Indonesia wearing a Chico Mendes t-shirt, the only Brazilian I’ve ever seen wearing a Mendes t-shirt was a staff worker at the Casa Chico Mendes Museum, which is where the activist was blasted by a twenty-gauge shotgun in front of his wife and children days before Christmas in 1988.“Visitors to the museum come from mostly other countries because the population from Brazil doesn’t really recognize the fight,” the museum worker told me.

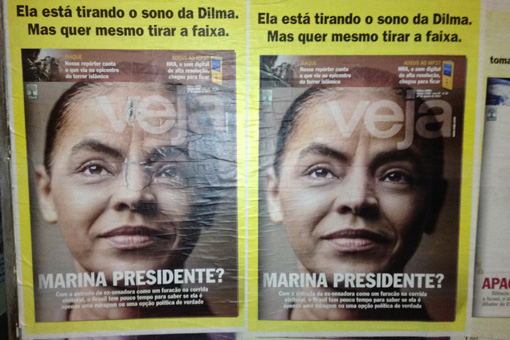

A magazine cover featuring Brazilian presidential candidate Marina Silva. Photo: Stephen Kurczy.

I would later relay all this to Sergio Abranches, a Brazilian social scientist and environmental writer, who was unsurprised. “Chico Mendes is absolutely more popular outside Brazil,” Abranches told me. “You’re more likely to find people who know about Chico Mendes at a university of the United States than at the University of São Paulo [Brazil’s top college].”

The unclear memory of Mendes reflects a larger indifference toward the environment and underscores the improbable rise of his protégé, Marina Silva, who has become the candidate of change amid Brazil’s social unrest and economic recession. If elected president, she is expected to continue his fight and provide new support for activists in the world’s most dangerous nation to be an environmental activist.

“Marina Silva’s presidency would make Brazil an extremely robust and important global environmental leader,” said Steve Schwartzman of the Environmental Defense Fund, who knew Mendes and also worked with Silva. “It would have enormous consequences.”

Brazilians go to the polls Sunday, and a second-round runoff is expected on October 26 between Silva and the incumbent, President Dilma Rousseff, who has recently lengthened her lead. The Amazon is a central election issue. Rousseff is an aggressive supporter of new roads and hydroelectric dams through the forest, while Silva wants stricter environmental oversight and support for renewable energy such as solar and wind.

But it can be hard to get Brazilians concerned about the Amazon, even if it covers an area eight times the size of Texas and accounts for more than one-third of Brazil’s landmass. About 90 percent of the population lives elsewhere, and their only contact with the world’s largest tropical rainforest comes when using the electricity generated from its dams. Surveys have shown a recent decline in environmental concern among Brazilians—coinciding with a 29 percent increase in Amazon deforestation, with an area the size of Delaware cleared last year. More than 1,500 Brazilians have been killed trying to protect the Amazon rainforest since the death of Mendes a quarter century ago, including 15 last year.

It’s even harder to get Brazilians concerned about the Amazonian state of Acre, birthplace of both Mendes and Silva. Bordering Peru and Bolivia, Acre is the most western state in all Brazil, three time zones away from the skyscrapers of São Paulo and the beaches of Rio de Janeiro. To say Acre is remote, sparsely populated, and inaccessible is an understatement. Mention it to a Brazilian and they’ll likely reply: “O Acre não existe” (“Acre doesn’t exist”). I flew into the tiny state capital of Rio Branco and connected with a friend researching Brazilian environmental policy—her excellent Portuguese made up for my language fumbles—and we took a three-hour taxi ride west over pot-holed roads to Mendes’s quaint little hometown, Xapuri.

Acre’s landscape is still scarred by massive deforestation. Cattle pasture and farmland stretch to the horizon in every direction, and little forest was visible until we neared Xapuri. Outside town is the Seringal Cachoeira, a protected area where Mendes woke early every morning to collect latex from rubber trees. His cousin, Nilson Teixeira Mendes, still works on the reserve as a guide showing visitors how rubber tappers would walk the trails and tap the trees. Nilson told me his life was also threatened during the 1980s, when he and Marina Silva participated in Mendes’s so-called empates, when groups of armed rubber tappers would forcefully dismantle the camps of deforestation crews.

“We were threatened because of having helped in the protests,” Nilson said as we walked the hard-packed jungle paths of Mendes’ old stomping grounds. “There were people pursuing me because of having helped Chico.”

The empates were a turning point. Mendes had banded together Indigenous peoples with rubber tappers and other extrativistas—forest-dwellers who harvest sustainable products—into a recognized group that could vocally oppose deforestation and land grabbing. “That was a great advance,” said Philip Fearnside, a longtime researcher of the Amazon and friend of Mendes. “Now you had an alliance between the two groups with similar interests.”

Mendes wasn’t charismatic, but he was understatedly charming and diplomatic, skills recognized by international groups looking for a figurehead. In 1987, several U.S.-based environmental groups flew the genial Brazilian to Washington DC to convince the Inter-American Development Bank, World Bank, and Congress to support the creation of extractive reserves. It worked, and the exposure helped Mendes receive several big international awards that brought international scrutiny of deforestation in the Amazon—and later helped add pressure on the Brazilian government to find and prosecute Mendes’s killers.

The memory of Mendes was strong back at the Seringal Cachoeira, Ground Zero in Acre’s environmental fight. But in Xapuri, I found an ambivalence toward Mendes and a chilling regard for his killers. It’s a cozy town with a collection of colorful food markets and stalls along the Rio Branco river, a winding tributary of the Amazon that once carried the region’s harvest of rubber down to the state capital and onward more than 1,000 miles northeast to the industrial hub of Manaus, and from there another 900 miles to the Atlantic Ocean.

Mendes’s death is eerily retold in Xapuri at his old wood-paneled home—hardly more than a shack—preserved as it was the day he died. Bloodstains are still on the kitchen wall where the 44-year-old was shot, with signs describing the scene in the first person as if the ghost of Mendes is retelling his death. ”I was coming close to the door and got shot in the chest,” reads one placard.

The shooter was Darci Alves Pereira, who had been assigned the job by his father, the rancher Darli Alves da Silva. Both went into hiding, and were only found months later amid international pressure on President José Sarney to investigate and prosecute. Each was sentenced to 19 years in prison. They escaped three years later and were on the loose for more than three years. Recaptured separately in 1996, they each still got early release, and seem to have returned to Xapuri with a sense of defiance.

The Alveses today shop at a general store operated by Francisco Ramalho de Souza, a participant in some of the first empates and a past president of the Rural Workers’ Union of Xapuri, a post Mendes also held. I asked if there was any tension with the Alveses. “Nobody is dying,” he responded. “We don’t want more problems.”

Down the street from Mendes’s old house is the Hotel Veneza, where I stayed the night. The drab concrete building was also a refuge for the reporters and television crews who descended on Xapuri following his assassination, according to the 1990 book The Burning Season by The New York Times reporter Andrew Revkin. “After a while,” Revkin wrote, “the woman who ran the Veneza learned that Americans do not like heaps of sugar brewed directly into their coffee, as is usual in the Amazon.”

That woman, Lindaura Viana, has apparently returned to her old habits. She’s run the Hotel Veneza for more than four decades, and brews a super-sweet coffee for anyone staying at her pousada. She seemed amused by my visit to Xapuri, but she wasn’t shy about telling me her opinion of Mendes. He provoked people, she said. He lost his campaign for state representative in 1982 and later for town mayor because people didn’t like him, she said.

I asked Viana what she thought of the rancher Darli Alves and his family, and she shrugged. “They’re hard workers,” she said, adding that they were family friends. Her son told me he could set up a meeting.

I couldn’t believe what I was hearing. I had expected a statue of Mendes in the town center, a street named after him, a modest tourism industry built up around the memory of a man whose martyrdom triggered a best-selling book, an Emmy-winning film, a song by Paul McCartney, and another by Maná. But this was like going to Martin Luther King’s hometown and getting an earful about the civil rights activist’s extramarital affairs and alleged communist ties, mixed with sympathy toward his killers.

I waited all the next day for that meeting—but in the end, her son said he couldn’t get in touch with the Alveses after all. But why not simply go and knock on Alves’ front door? I hired a taxi for the trip back to Rio Branco, and told the driver, Lucas da Cruz, that I wanted to make a stop along the way.

As we rolled out of town, I asked da Cruz if he knew of Darli Alves. He nodded. I asked if he knew where Alves lived.

“Yes, up here,” he said. “My wife is his sister.”

He looked at me in the rearview mirror and laughed, seeing my surprise. “He’s a good man,” da Cruz added. “A hard worker.”

I asked if we could make a quick stop, but da Cruz said his brother-in-law wasn’t home. He dialed his cell phone to call Alves, but got no response, and said he’d try again later. He pointed left out the window at a closed gate to a dirt road through an open field: Alves’ ranch.

I asked if Mendes ever came up in discussion at the family dinner table—and it’s a big table, so to speak, as Alves is said to have had some 30 children with numerous wives, which da Cruz confirmed.

“He says he didn’t kill Chico Mendes,” da Cruz told me. “He says Chico Mendes killed himself. He looked for death. I agree. Chico Mendes wasn’t what people say. In reality, he was a drinker. He drank a lot of cachaça.”

A local lawyer named Carlos Almeida was also traveling in our taxi, and he interjected.

”Everybody has a different story to tell about his life,” Almeida said. “All of them are true. The local image of Mendes is not positive. But there’s a good image from people who know how to separate his life from his work.”

“Wasn’t he a hero?” I asked.

“Hero of what?” our driver replied. “I don’t know why so many Americans come to see Chico Mendes’ house. There’s nothing to see here. Nothing that matters.”

Several days later, da Cruz back with an invitation to return to his brother-in-law’s ranch: Alves had said he would speak with me for a fee of $20,000.

Had I met Alves, I’m unsure what I would have asked. Perhaps: Who are you voting for on October 5?

Marina Silva might not have been the oddest answer. The Amazon would be central to her policy, but she’s also made a pro-agribusiness congressman her vice presidential candidate—perhaps showing something that she learned from Mendes about creating alliances, and also signaling a truce between environmentalists, ranchers and farmers, that Brazil is big enough for the both of them, even in tiny Xapuri. Among those people campaigning on Silva’s behalf, in fact, is one of Alves’ own sons.

“Marina could change the narrative of Mendes,” said the sociologist Abranches. In so many ways.