There is a truly extraordinary gap today between how the world sees Colombia, and how Colombia sees itself.

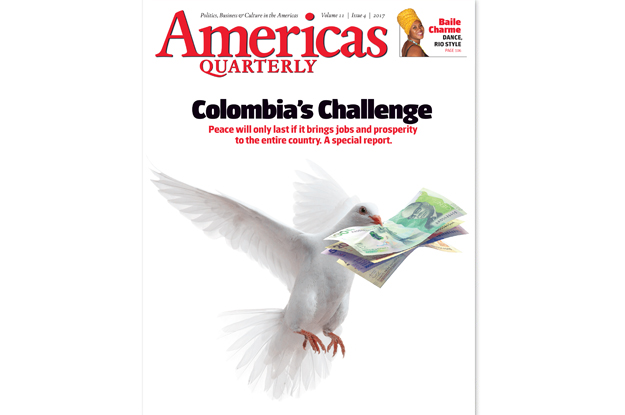

To most outsiders, Colombia is a spectacular success story – the country that defeated kidnappers and cocaine kingpins, and stepped back from the brink of becoming a “failed state” in the 1980s and 90s. Home to the urbane president who struck a peace deal with the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia, or FARC, and won the Nobel Peace Prize in 2016.

To most Colombians, that rosy view is out of date – and out of touch.

The economy has been sluggish for years. Corruption scandals have severely eroded faith in the political establishment, which now enjoys the support of just 7 percent of Colombians – a third the level in February. Coca cultivation has soared 50 percent in just the past year. New violence has broken out in areas including Nariño, near the Pacific coast. And whatever pride people feel over the FARC deal has been complicated by questions over the cost – and fairness – of its terms.

In this new issue of Americas Quarterly, we took an in-depth, honest look at how Colombia can best address these challenges.

We found that, after so much focus on peace in recent years, Colombians are yearning for solutions to more “normal” problems. They include unemployment, education, corruption and infrastructure. For our cover story, journalist John Otis traveled to a former FARC stronghold to show why it’s precisely those issues that will most determine whether the peace deal fully takes hold – and endures.

Bringing prosperity and jobs to the entire country won’t be easy. There are vast areas where the federal government has never really exercised power – and the quality of Colombia’s roads ranks just 120th out of 138 countries worldwide, according to one study. Among Latin American countries, only Haiti suffers from greater inequality. But John found several examples of creative entrepreneurs who, if they could only gain access to better financing and infrastructure, would surely thrive in the global economy.

Elsewhere, Lisa Viscidi showed why getting basic infrastructure like electricity to long-neglected areas is so hard. Sibylla Brodzinsky looked ahead at the 2018 election and one of its most controversial candidates, former Bogotá mayor Gustavo Petro. And Adriana La Rotta penned a heartfelt, thoughtful reflection on how far Colombia has come, and why its future still appears bright.

Indeed, Colombia has come so far in the last 15 years – further than anyone thought possible. Continuing down that road will require renewed focus on an old – but still unsolved – set of problems.