In 2013, Nataliya and Daniel Ulasik started their own business in Quito, Ecuador. The business, EcuaLama, enables Indigenous people in the small Ecuadorian mountain town of Otavalo to sell handmade blankets, ponchos and hats to consumers in 30 countries. The company’s online sales and marketing eventually led to a relationship with a London-based retailer. Today, as a result of communications technology, goods from Otavalo are sold in London.

To consumers who have grown up in this era of deepening globalization, this may seem like an unremarkable story. But, until recently, it was entirely improbable.

If you’re a budding entrepreneur, the benefits of globalization can seem remote. Traditionally, businesses have needed significant resources to develop a global consumer base and deliver a product or service efficiently across borders. That’s why, as research has consistently shown, only the largest corporate players have been able to take full advantage of the trade opportunities created by the rise of a global marketplace. However, that’s all changing thanks to the Internet.

The information and communications technology (ICT) revolution has generated a new trade model—one that enables businesses of all sizes to trade directly with businesses and consumers across borders. Increased connectivity, combined with sophisticated logistical networks for the transport of goods and innovations in online services such as marketing and payments processing, have fostered a trading network that is empowering a new generation of businesses around the world—including in Latin America.

This network, which the eBay Public Policy Lab has been studying for the past four years, is still in its early stages.* Measuring its size and reach is a challenge. EBay’s study analyzed online business activity in Brazil, Chile and Peru. Researchers compared data from eBay and PayPal with information on traditional businesses from the World Bank, national governments and the United Nations Comtrade Statistics Database. The study demonstrates that among businesses in Latin America—particularly small businesses—technology-enabled small businesses (TESBs—those using eBay Marketplaces or PayPal) experienced higher export growth rates, were more diverse in terms of firm size, and were more likely to export to a greater number of markets and to survive than their traditional counterparts.

How e-Commerce Drives Exports

Most traditional firms do not export at all. Academic literature shows this to be the case across a wide range of countries. According to research, only 4 percent of U.S. firms export—the percentages are similarly low in Europe.1 This is no different in Latin America. Brazil is home to over 6 million small- and medium-size enterprises (SMEs), which represent 99.7 percent of Brazilian enterprises and 52 percent of Brazil’s formal jobs.2 The vast majority of Brazilian businesses, however, do not export. The World Bank reports that fewer than 20,000 Brazilian businesses engaged in exporting in 2010—less than 1 percent.3

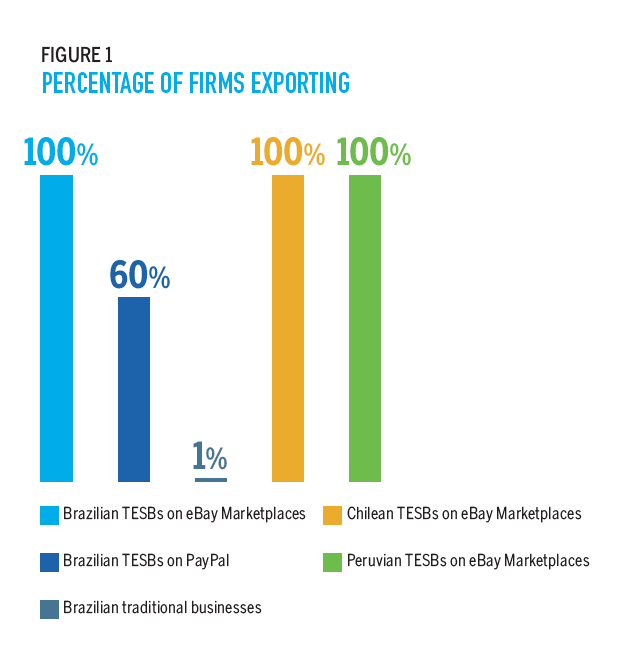

The story is dramatically different for TESBs. Data show that, in 2013, 100 percent of businesses in Brazil, Peru and Chile that use eBay Marketplaces exported their goods or services.4 Similarly, about 60 percent of Brazilian businesses using PayPal were exporters in 2013.5

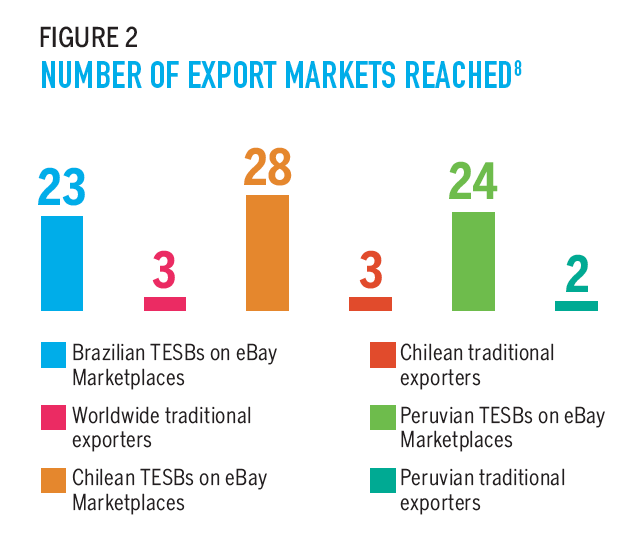

TESBs also reach far more markets than traditional businesses. A 2012 World Bank survey of exporters in more than 40 countries—including Chile, Peru and Brazil—shows that the average number of countries reached by traditional exporters is very small. On average, traditional exporters served only three different national markets.6 In contrast, TESBs in Chile, Peru and Brazil reach an average of 25 national markets.7

Access to more export markets provides tremendous growth opportunities to Latin American TESBs, and data from Brazil demonstrate the positive impact these new markets can have.

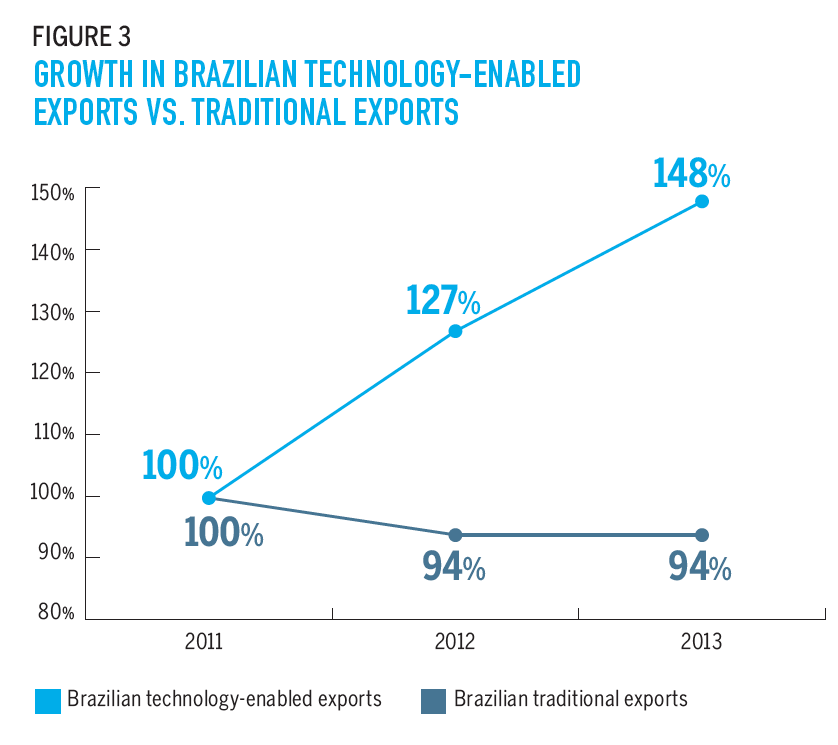

Exports from Brazil experienced a period of healthy growth from 1999 to 2011. But since 2011, the traditional export market has slowed.9 In 2013, exports from Brazil were 6 percent lower than they were in 2011.10 Meanwhile, in 2013, TESBs in Brazil experienced 48 percent more crossborder sales than they did in 2011. This growth has been particularly pronounced in emerging markets. For example, Brazilian TESBs grew their overseas sales between 2007 and 2013 to other parts of South America by 74 percent, to the Asia-Pacific region by 62 percent and to Africa by 47 percent.

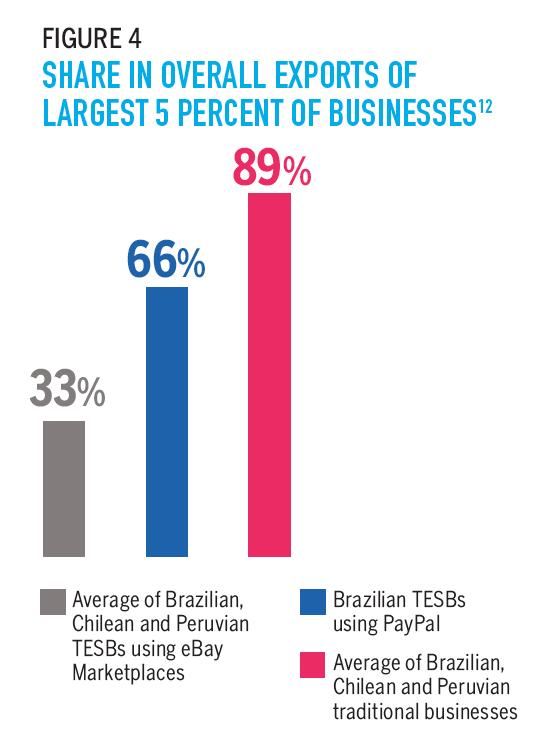

Traditional trade is dominated by a small number of very large firms.11 This is not to say that new firms will not enter, that newcomers will never become large or that large firms will never disappear. Yet, it appears that the traditional global trade environment is particularly challenging for entrepreneurs and small firms.

Brazil, Chile and Peru are no exception to this trend. The largest 5 percent of businesses accounted for 84 percent of Brazil’s exports, for 92 percent of Chile’s exports and for 91 percent of Peru’s exports.

However, a detailed analysis of the composition of export activities reveals that the technology-enabled marketplace in Latin America is far less concentrated than the traditional export market. The share in overall exports of the largest 5 percent of TESBs in Brazil using PayPal is 66 percent, while the share of the largest 5 percent of businesses using eBay Marketplaces in Brazil is 28 percent; in Chile, the figure is 33 percent; and in Peru it is 37 percent.

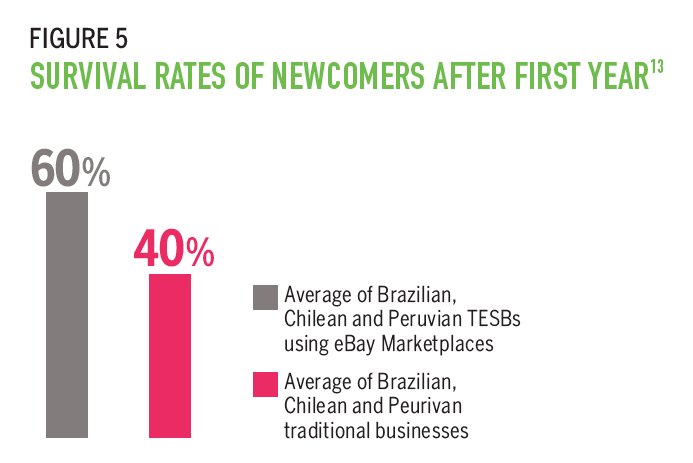

A Better Chance of Survival

TESBs in Latin America have a much higher chance of remaining in the market. About 60 percent of new businesses on eBay Marketplaces survive their first year, whereas only around 40 percent of traditional exporters in Latin America remain active in their second year.

Minding the Policy Gap

Trade policy in Latin America and around the world has traditionally focused on large enterprises. This is not without good reason—they were the only actors engaged in a significant level of global trade. Ensuring the success of Latin American TESBs now requires a new approach by policymakers. These enterprises face trade issues that are different from their larger, traditional counterparts, and governments need to take those differences into account to foster continued growth. Following are four essential priorities that will foster the development of e-commerce in the Americas.

Educate on the Value of Connectivity

Internet connectivity remains a major challenge in the region. Average Internet penetration across Latin America is around 50 percent, and, in countries like Bolivia and Paraguay, this number can fall below 40 percent.14 Even in countries where Internet penetration is relatively high, such as Brazil, the Internet is not being used as a positive tool for growing local commerce. The Brazilian government’s Ciência sem Fronteiras (Science without Borders—CsF), a multiyear initiative aiming to send 101,000 fully funded Brazilian students abroad for training in science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM) fields by 2015, is a great example of encouraging entrepreneurship.15

But fostering a community of software developers is only the start.

Many businesses want to take advantage of the Internet, but they don’t know how. Governments can help to educate traditional offline businesses by promoting business education seminars or even by creating platforms that link traditional businesses with digital experts in the public and private sectors. The Inter-American Development Bank’s (IDB) ConnectAmericas platform—an online community for Latin American businesses to connect, learn and seek out financing opportunities—is a good model and should be expanded as rapidly as possible to businesses of all types and sizes across the region.16 The initiative could be better integrated and leveraged by national governments in their Internet and entrepreneurship-related initiatives.

Improve Access to Innovative Financial Services

Electronic payments drive e-commerce. If a business is unable to accept a trusted form of online payment, then doing business in another country will be a challenge. Over 70 percent of Latin America remains unbanked, and that means many are unable to enjoy the benefits of electronic payments.17 The key to bringing more people into the financial ecosystem will be creating regulatory policies that fosters an environment of inclusion and innovation.

In April 2014, Colombia’s Ministries of Finance and Information Technology and Communications introduced a new bill called Inclusión Financiera: Pague Digital (Financial Inclusion: Pay Digitally). The bill seeks to increase access to online payments, wire transfers and lower cost transfers. It also creates a new type of financial entity known as sociedades especializadas en depósitos y pagos electrónicos (organizations specialized in electronic deposits and payments) that simplifies the process of opening an account for online payments. Moreover, in late 2013, Brazil created uniform standards for the mobile payments sector, designed to promote interoperability.18 Models similar to the ones being used in Colombia and Brazil could be followed throughout Latin America to further the goal of financial inclusion.

Increase Access to Finance

In 2013, the World Trade Organization’s sixth trade policy review of Brazil found that insufficient access to credit contributed to the country’s economic slowdown over the past few years.19 Small businesses traditionally have the most difficulty in accessing capital, but online platforms have created new access opportunities for these businesses. Crowdfunding, for example, enables entrepreneurs to secure an influx of capital from millions of people. Working capital platforms provide entrepreneurs access to smaller loans in so they can make short-term investments, and microfinance models provide traditional financial products in a more tailored and efficient manner. Regulations surrounding finance have struggled to account for the rise of these new financing models. New regulatory approaches can encourage the development of low-cost models for access to capital by TESBs. Moreover, governments can provide guarantees for small-business loans so that risk profiles are lowered and more lenders enter the market.

Simplify Customs Rules

Returns are a part of operations for any business that sells goods. But exporting businesses must fill out customs paperwork and pay duties on returned items sold outside their borders if the value of those items is above what is called a “de minimis” threshold. Rather than offering returns, many times a business from a country with a low de minimis threshold will refuse to offer returns or will simply ship a new product rather than dealing with the hassle and cost of receiving a return.

De minimis levels vary widely across Latin America. Brazil does not impose a de minimis value, but instead applies a 60 percent flat import tax on most manufactured retail goods imported via mail and express shipments. Chile does have a de minimis level, but it is a mere $30.

Peru, in contrast, has its de minimis threshold set at $200.20 This enables Peruvian businesses to offer returns on their products and minimizes costs and delays for Peruvian consumers. But other countries outside the region have even higher de minimis levels. In the U.S., legislation has been introduced to increase the de minimis threshold from $200 to $800.21 Australia’s is $1,000, leading to the strong growth of technology-powered exporters in the past few years.22 Likewise, Latin American countries should consider raising their de minimis levels to facilitate TESB trade.

The Promise of the Global Empowerment Network

The vast majority of small businesses in Latin America have yet to come online and enjoy the benefits of e-commerce. The opportunity for growth is real. A group of researchers writing for the World Bank estimates that reducing the trade costs for offline trade flows to the level found for online trade would result in a 29 percent increase in real income, on average, in the 56 countries studied. Notably, the study estimates that Brazil is the country with the largest potential gains, at over 80 percent.23

Our research suggests that when Latin American businesses come online, they will export more and enjoy greater growth, less concentration and more opportunity for building a lasting business. However, Latin American policymakers must take note of the growth of TESBs and provide a framework that enables global growth. The potential for inclusive economic growth is achievable, but the right policy regime must be put in place to realize maximum benefit.