This piece was updated on June 22

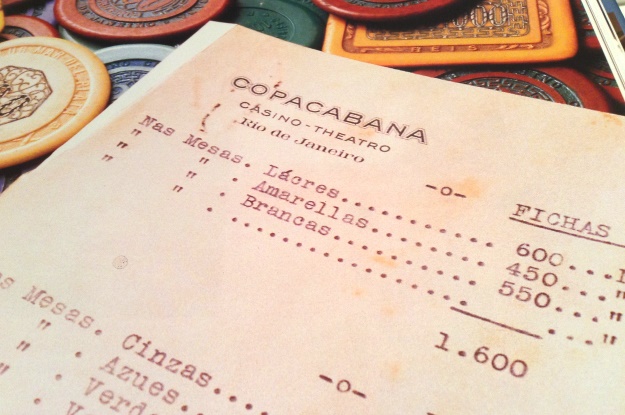

In 1946, the last year casinos were legal in Brazil, the ritzy Copacabana Palace in Rio de Janeiro was pulling in nearly $100 million a year from roulette and other table games. A frequent gambler was Benjamin Vargas, brother to a former president, who was notorious for chasing away bad luck by firing bullets in the air.

The money, the jobs and – some worry – the shady characters may soon be returning.

A growing number of Brazilian legislators want to roll the dice on gambling as a source of billions of dollars in new tax revenue. Amid signals of support from interim President Michel Temer and his cabinet, some analysts predict Brazil could reopen to casinos and legalize bingo halls, online gaming and sports betting just as the Rio Olympics are set to kick off in August.

Brazil is following a trend across Latin America in which casinos, slot parlors and racetracks are proliferating as governments increasingly try to regulate illegal gambling and find ways to shore up their budgets; Argentina has doubled its casinos and betting halls since 2007 to more than 150, Bolivia awarded its first casino license in 2014, and Mexico’s Senate is now reviewing a new federal betting law, according to a report published last month for the annual Juegos Miami gaming conference.

But analysts say Brazil’s legislation would be a game-changer.

“If you ask me what are the odds of Brazil becoming a global gaming destination within the next five to 10 years, I would say they are quite high,” Alexandre Fonseca, a Brazilian gaming analyst who is advising members of Congress on the legislation, told AQ. He said he heard speculation that U.S. casino operator Sands was looking at Brazil as its first South American subsidiary.

A Senate committee in April passed legislation (known as PLS 186/2014) that would authorize the government to license up to 35 casinos, with each required to provide non-gaming attractions such as hotels, restaurants and retail. A bingo hall would be allowed for every 150,000 residents, and online gaming would be legalized alongside the numbers game jogo do bicho (“the animal game”), widely played but outlawed since 1946.

In coming days the House is expected to introduce its own gaming bill (PL 442/1991), after which the House and Senate would need to reach agreement on common legislation for Temer to sign. Lawyer Cristina Romero of Madrid-based LOYRA, a gaming boutique that advises governments and private stakeholders, said her firm expects “some delay in the passing of the bill or even some alternative regulatory routes.”

Other analysts are more optimistic. Todd Eilers of California-based Eilers Research foresees Brazil’s first casino opening in 2019 at earliest and expects interest from European companies Codere of Spain and Novomatic of Austria, as well as the U.S. companies Las Vegas Sands, MGM Resorts International and Wynn Resorts.

“This year’s expansion proposal has the best odds of passing in over a decade due to the current state of the Brazilian economy and desperate need for additional tax revenue combined with growing political support,” Eilers wrote in an April report, adding that this would represent the global gaming market’s single largest expansion since the U.S. legalized casinos on Native American reservations in 1988.

Sands and Wynn did not respond to requests for comment, but a spokesperson for MGM told AQ the firm was “carefully monitoring the legislation in Brazil to determine if it provides an appropriate opportunity for our company.”

Assuming all 35 casino licenses are awarded and each casino uses its maximum allotment of machines, Brazil could have as many as 70,000 slot games; the entire Las Vegas strip has about 45,000 slots. Brazil’s pending legislation also allows for up to 1,333 bingo halls with a total of 666,500 video bingo machines – more than six times the number in Mexico, which partially legalized gaming in 1948.

“The demand for gambling in Brazil is huge,” said Edgar Lenzi, president of Curitiba-based gaming consultancy BetConsult.

Lenzi estimates legal betting is already a 14.2 billion real ($4.2 billion) market in Brazil, primarily from state lotteries, while illegal gambling totals close to 20 billion reais per year. An estimated 200,000 Brazilians gamble abroad every month.

Brazil’s tourism minister has projected that legalized gambling could itself generate up to 20 billion reais annually in new tax revenue. That’s a lot of money to turn down, especially amid a soaring budget gap. But the legislation has powerful opponents, including social conservatives and others who argue casinos will facilitate money laundering and be a step backward in fighting corruption – a reputation not helped by a 2004 scandal involving a presidential aide caught taking bribes from a lottery boss.

“It’s very easy to think about taxes going to the public coffers,” Pastor Francisco Eurico da Silva, a member of Congress’ evangelical bench, said of the legislation. “It’s forgetting how many families will lose, will be destroyed by those who … take everything they have and play at the casinos.”

These social tensions are clear today at the Copacabana Palace, where there is both nostalgia and ambivalence toward casinos. Inside the gift shop, a coffee table book laments how “the closure of the casinos (which numbered 79 throughout the country) represented not just the end of a golden era in Rio but unemployment for almost 40,000 people, including the performers and technicians involved in the entertainment industry, the natural business partner of gambling.”

While one hotel employee told AQ the legislation was “dangerous” and would worsen corruption, a concierge said he welcomed it as a way of boosting the economy. Whenever visiting Brazil’s south, he said, he always visits nearby Argentine casinos with a few hundred dollars to play the tables.

“If you go to the first casino in Argentina, you’ll find more Brazilians than Argentinians,” he said. “I’d love to be able to gamble in Brazil.”

—

Kurczy is a special correspondent for AQ.