This article is adapted from AQ’s most recent issue, “Fixing Brazil.” To receive the print edition at home, subscribe here.

The date was October 12, 2010, and Brazil’s finance minister was addressing New York’s financial community under crystal chandeliers at the Americas Society/Council of the Americas. Two weeks earlier, Guido Mantega had caused a sensation by denouncing a global “currency war” that was generating huge capital inflows to Brazil, making the real dangerously strong. But on this day, Mantega seemed cool and confident. He noted this headache was fundamentally a result of foreign investors being so eager to invest in Brazil’s economy, which would grow a China-like 7.6 percent that year.

Today, it’s jarring to remember how optimistic most people in that room were — and how wrong. Not long afterward, Brazil’s economy began a long fall from grace that has culminated in its worst recession on record, and a predictable amount of finger-pointing as well. Yet I would like to suggest that the crisis remains one of the most misunderstood chapters in the recent economic history of Brazil. And the failure to grasp what actually happened and why it poses significant risk to Brazil’s prospects for recovery, as well as to the investors — local and foreign — who are currently betting on it.

Most Brazil-watchers believe the blame belongs at the feet of Dilma Rousseff, who became president on New Year’s Day, 2011, not quite three months after that event at AS/COA. The standard critique holds that Rousseff and Mantega (whom she kept as her finance minister) overreacted when the economy began to slow that year, turning to a seemingly endless set of stimulus measures. It was tax cuts for automakers and shoemakers one month, then lower electricity rates for manufacturers the next, then hefty tariff increases after that.

The popular diagnosis holds that Rousseff’s unpredictable policies not only failed to temper the downturn, but actually worsened it by aggravating an already worrisome imbalance between public-sector revenues and expenditures. The casualty? Brazil’s long-heralded primary fiscal surplus, which acted as an anchor for investor expectations under Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, Rousseff’s predecessor — but was gone by the time Rousseff’s first term ended in 2014. Lacking a fiscal anchor and facing worsening growth numbers and an increasingly hyperactive industrial policy, investors lost faith. Eventually the economy succumbed to the nasty downward spiral that characterized Brazil by the beginning of 2016.

It’s easy to understand why this “fiscalist” version of events is so popular today. Rousseff’s mandate has ended following her impeachment in August. Meanwhile, the new government of President Michel Temer has promised to tackle Brazil’s fiscal problems head-on with a proposed constitutional amendment that would cap much of government spending growth at or below inflation. In practice, the amendment will force an overhaul of Brazil’s pension system, which should in turn help to reverse (eventually) the worrisome growth of Brazil’s public debt relative to gross domestic product, currently at about 74 percent. Many investors have bought into Temer’s plan, and poured money into Brazilian assets in recent months.

But here’s the problem: I believe that Rousseff’s industrial policy, and her mismanagement of the fiscal accounts, were not the causes of Brazil’s current mess. Instead, Rousseff’s policies were flawed responses to Brazil’s much more serious challenges — which began building up many years before Rousseff took office.

Indeed, the country was already in trouble on that day in late 2010 when I listened to Mantega compare Brazil’s growth prospects to those of China. In 2010, Brazil had a structural growth problem. And sadly, it still does. Unless and until this problem is understood and addressed, I am afraid that most of the reforms being heralded today will not have their desired effect.

A Problem of Productivity

Brazil’s biggest obstacle to growth has many faces, but can be summed up in a single word: productivity.

Brazilians, and anyone who has spent time in Brazil, know the depth of this problem. I tend to think of this as a three-pronged challenge involving human capital, physical capital, and the regulatory environment.

With human capital, the problem in Brazil starts in the first years of schooling. The quality of its primary education was ranked just 132nd out of 140 countries surveyed by the World Economic Forum (wef) for its Global Competitiveness Index, and higher education was not much better. On physical capital, Brazil ranked 121 in the same WEF survey for the quality of its roads and 120 for its ports, posing massive challenges to farmers for what should be one of Brazil’s strengths — its agricultural exports. Meanwhile, Brazil’s regulatory environment brings the worst news of all: The WEF rankings on the burden of government regulation puts Brazil in 139th place (ahead only of Venezuela), while the World Bank’s Doing Business Survey puts Brazil 174th out of 189 economies in the 2016 report for starting a business and 178th for the difficulty of paying taxes.

My fear is that most of the macroeconomic plans and proposals being discussed today are likely to have little effect on Brazil’s long-term growth path if these arguably more important barriers are not tackled.

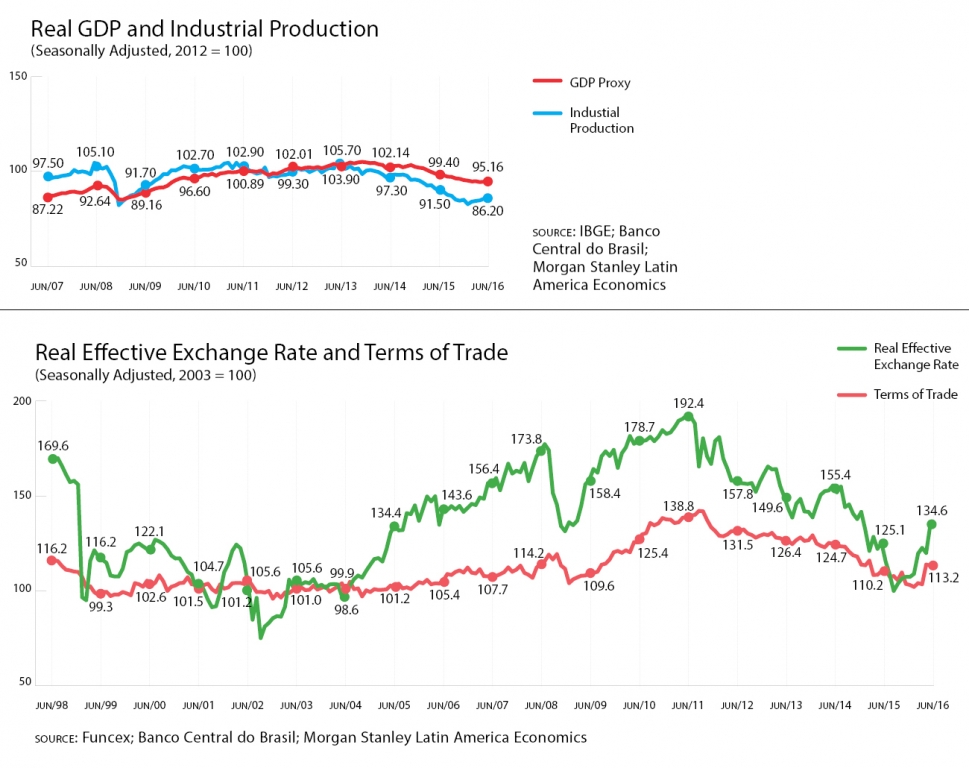

Some might ask: If these structural limitations are so severe, then how was Brazil’s economy able to experience such a strong boom last decade? Here, the example of 2010 is instructive. That year, Brazil’s real effective exchange rate reached its strongest level in decades (see the graphs above). Interestingly enough, this occurred just as Brazil’s terms of trade (the relationship between export and import prices) also reached a multidecade high thanks to global factors beyond Brazil’s control. Put another way: Prices for Brazilian agricultural and mining exports were so high, thanks to demand from China and elsewhere, that it helped mask the deeper problems — at least for a time.

Indeed, Brazilian consumers in 2010 were euphoric as they enjoyed an important boost to their purchasing power, which, along with a credit boom, helped to explain the crowded shopping malls and strong retail sales numbers that excited so many investors at the time. An entire generation had never held a currency with so much purchasing power, causing an exodus to places like Miami and New York where Brazilians were notorious for filling their shopping carts.

But there was a flipside — the damage that was being done to Brazil’s manufacturers. A strong currency boosted demand for imports, which began to undercut domestic producers — who simply could not compete, due to the structural challenges already listed. Before long, this “growth mismatch” between deteriorating output and robust demand inevitably caught up with the rest of the economy — and Brazil began to face anew the twin risks of a balance of payments challenge and an inflation challenge. Simply put, measures to enhance Brazil’s productivity had not kept pace with the currency’s dramatic gains in the years leading up to 2010.

The solution that Rousseff should have undertaken wasn’t another package designed to boost domestic demand. Brazil’s problem in 2011 — and Brazil’s problem today — is more structural than cyclical. Instead, she should have embraced a different set of measures, starting with a much more ambitious infrastructure opening to private players to address Brazil’s shortfalls on ports, roads and railways. And despite the laudable progress that Brazil has made in improving access to education, the challenge now is to improve its quality. On the regulatory front, the list of what is needed is long: from simplifying the tax code, to reducing the tax burden itself, to streamlining the administrative regulations governing starting and running a business.

Challenges Are the Same

Today, the dilemma facing President Temer is essentially the same, even if 2016 may seem unlike 2010. Yet there is precious little discussion of the kinds of reforms that Brazil needs to boost its long-term potential for growth. Instead, the focus has been on fixing the fiscal accounts. Doing so may continue to be greeted by an upturn in investor sentiment. And I understand part of the optimism. After all, there is little doubt that Brazil needs to get its fiscal house in order. But I would argue that Brazil’s fiscal profligacy is largely the consequence of Brazil’s weak growth and low productivity record and not the other way around.

Until Brazil undertakes a meaningful new agenda to improve productivity, I fear we may see this cycle of ups and downs repeat itself once again. It is easy to see why investors all too often get caught up chasing the latest swings in sentiment and flows. My hope is that Brazilian policymakers do not make the same mistake.

—

Newman is adjunct professor at the School of Public Affairs at Columbia University. He retired in 2014 from Morgan Stanley, where he was a managing director and chief economist for Latin America. This article is adapted from a chapter in a forthcoming book on Brazil edited by Albert Fishlow and Sidney Nakahodo of Columbia University.