The literature of Alejandro Zambra is one of both movement and repose.

On one hand, his work — reflected in titles such as Ways of Going Home, Bahía Inútil and Mudanza — brings to mind an expert in packing bags, works of few pages that speak to a traveler who knows in advance that the weight he carries will one day impose itself on his surroundings. Zambra’s writing reveals an extreme weakness for the ephemeral; he is an author who, instead of trying to mold a creation, is attempting to carve one out from the ether.

But Zambra is also concerned with the way we situate ourselves once we’ve arrived in a given place — repose, in a traditional sense. Bonzai and The Private Life of Trees, for example, refer to that other stage of a travelers’ trajectory, to the circuits of the hallway or the yard, to discovering one’s own home, such as it is.

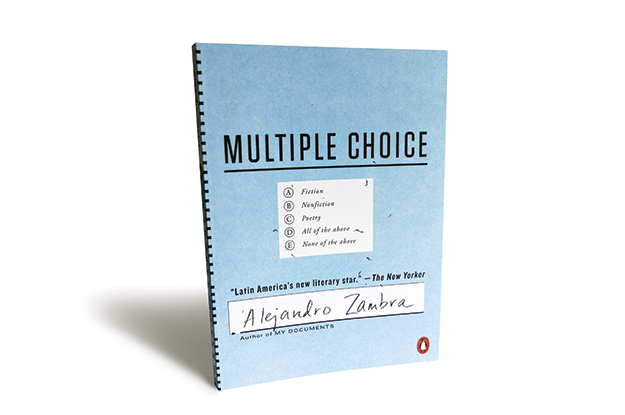

It is no surprise, then, that readers of Zambra’s latest work, Multiple Choice (translated by Megan McDowell), are faced with an examination of their lives both in motion and at rest. What might be less expected is just how literal that test turns out to be.

A novel, of sorts, Multiple Choice is written entirely in the format of the familiar standardized tests of bygone school days. (Zambra drew its structure from the tests taken by literature students in his native Chile.) The book, for example, prompts the reader to “mark the answer that corresponds to the word whose meaning has no relation to either the heading or the other words listed,” followed by a series of possible responses. With questions that vary from the absurd to the existential, Zambra suggests to his readers that the choices made in life are devastating, contradictory, valid and invalid, all at once. In our journey, in our trajectory, all categories of experience are left to be questioned: the political, sexual, laborious, paternal, amorous — the very act of writing. Life, according to Zambra, contains the same degree of chance and uncertainty as a test answered entirely at random.

To what end? When I consider Zambra as a generational author, as his contemporary Daniel Alarcón described him, I think that it is because he is able to capture the solitude of the homes that my generation inhabits. They are transient places, maladjusted and dismantled; home is no longer the family, but perpetual movement, perpetual choice. When we leave — wherever we leave — we think of return as a return to the homes of our parents, while our parents’ return is to a home of their own. Their home is stable, unchanging. Ours has multiple correct answers. Or none at all.

—

Londoño is a writer and editor from Bogotá based in New York.