The International Commission against Impunity in Guatemala (CICIG) has been key in Guatemala’s fight against corruption. The UN-backed body has, over the past 10 years, taken on complex tasks that the state recognized could not be accomplished independently: It has investigated the operation of illegal security forces and illicit economic political networks; it has collaborated with state institutions to dismantle these networks; and it has promoted the prosecution of related crimes.

Working outside government, without attending pressures from interest groups, CICIG has exposed scandals involving presidents, ministers, congressional representatives, business executives, military officials, judges, and others close to political power. Its first commissioner, Carlos Castresana, helped hone laws that have become valuable tools in criminal prosecution. He also paved the way for his successor, Iván Velasquez, whose investigations led to the ouster of former President Otto Pérez Molina, and now threaten to topple President Jimmy Morales.

CICIG’s work has helped Guatemalans face corruption in government, but the essential work of reforming the system is up to Guatemalans themselves: It will require political will, the pursuit of joint strategies with national actors, and the promotion of public policies and legal reforms to strengthen institutions capable of taking on corrupt practices.

So far, we haven’t seen that. Despite running a campaign slogan that promised he was “not corrupt, not a thief,” when Morales was confronted with an impeachment process by CICIG and the attorney general on charges of illegal campaign financing, he decided to expel commissioner Velasquez and declare him “persona non grata,” with tremendous international repercussions. This decision was voided by the Constitutional Court, and the commissioner remained.

Then, it was Congress’s turn to show its true colors. It could have deprived Morales of immunity, but members decided instead to protect him. And more: Congress decided to pass a bill that would curb penalties for engaging in illegal campaign financing, among other changes, protecting the president and themselves from punishment. The furious reaction of Guatemalans forced them to roll back the legislation, but it deepened the political crisis facing the country.

This case also revealed the extent to which the political elite is not ready to fight corruption, but on the contrary continues to promote and defend it.

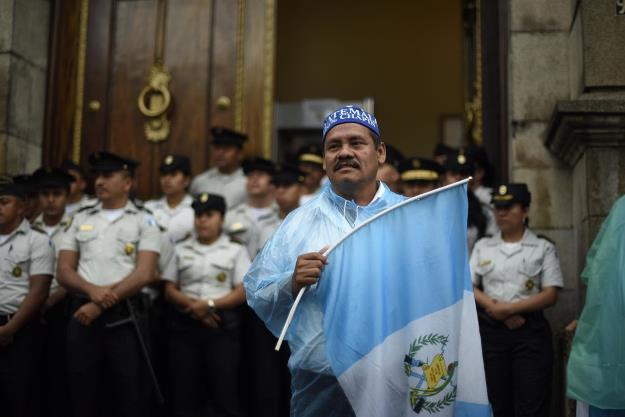

The population of Guatemala, however, has had enough. Tens of thousands took to the streets on Sept. 20 to protest the self-serving actions of Morales and of Congress, in a repeat of the great protests that preceded Pérez Molina’s resignation. It’s high time Morales, and members of Congress, paid attention.

The Guatemalan citizens are tired of the corruption scandals. They have expressed their rejection of the current system openly. However, the electoral reforms necessary to put in place new representatives have not taken place, and neither have the changes that would make the judicial system strong and efficient enough to punish wrongdoing.

The consequences of this are visible. A place where the rule of law is not respected becomes anarchic. There are areas of the country where there are no institutions, simply ruled by force. In Guatemala, this means drug cartels, gangs, mafia and corrupt politicians. This prevents development, generates violence, creates legal uncertainty, and violates human rights. The instability of the region is such that some landowners are losing their properties to invaders or raiders. Drug lords and gangs have control of entire villages, driving people away from the countryside by the thousands, in search of a safer place to live.

CICIG was not created to replace public institutions, and should not do so. Its success in criminal prosecution goes hand-in-hand with the attorney general’s office, which functions well partly as a result of CICIG’s capacity-building work with national prosecutors and investigators. More is needed: The judicial system still needs deep reforms to streamline processes and to eliminate the interference of political power in the appointment of judges if it is to perform effectively.

In fact, if Guatemala is to overcome the challenges of impunity and corruption, it needs major surgery – a total structural transformation of the political and administrative systems is required. Urgent changes are needed in electoral and political party law; the civil service must be modernized and professionalized; the judicial system needs increased funding for institutions, updated laws, and revamped internal review processes.

Congress is key in this transformation. To start, lawmakers should reform the constitution on issues such as the election of judges, judicial tenures and how resources are allocated and managed by the judicial body. It should also increase the budget of institutions responsible for justice and security, which includes the prosecutor’s office, the judicial branch, the National Institute of Forensic Sciences, as well as the national civil police and prisons.

If Guatemalans let the system that allowed impunity and corruption to stay as it is, then it will not be possible for the country to face the challenges of dealing with organized crime. CICIG will not last forever, especially without the political will to prolong its mandate.

As a judge, a legal scholar, and a Guatemalan, I hope that the commission will stay for years to come because Guatemalans need it now more than ever. The Guatemalans who want transparency, accountability and rule of law cannot fight alone against powerful networks of criminals. CICIG is necessary so that, one day, local institutions will be able to succeed by themselves, and the country can start walking independently on the road to freedom, development, and prosperity.

—

Escobar is a former magistrate of the Court of Appeals of Guatemala. After renouncing her re-election to the court in 2014, she blew the whistle on a corruption case involving central figures in the Guatemalan government. She left the country with her family in 2015, following a series of threats she received after continuing to speak out against corruption in Guatemala’s judiciary.