This article is adapted from AQ’s print issue on youth in Latin America.

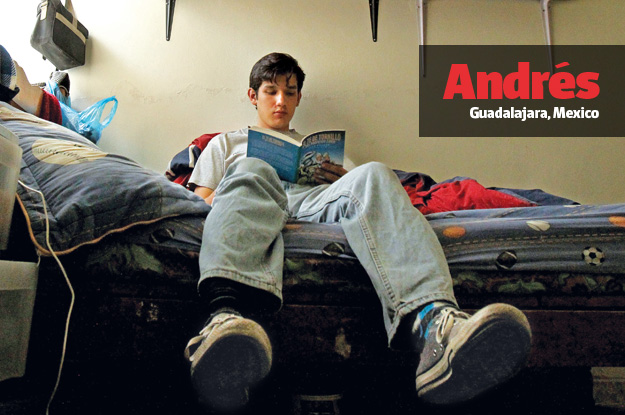

At 18, Andrés knows exactly what he wants: a job in an analytical chemistry lab and a beautiful wife.

It sure is hard to get there, though. Reaching that first goal — becoming a chemist — means getting up at 4 a.m. in Puente Viejo, a rural village two hours outside Guadalajara where he lives with parents, three sisters and a brother. Every day before dawn, his dad drops him off at a bus stop.

More: How better public transportation could improve Andrés’ job prospects.

The first bus ride takes Andrés into the center of town; the second drops him off near the Instituto de Ciencias, a preparatory school where his knack for science won him a scholarship.

Chemistry comes easily to him. The first year he took it in high school, he scored a perfect grade. In the two years since, it has shaped his approach to problems outside the classroom, Andrés explained. Recently, after an attempt to give two friends dating advice backfired, he created a diagram that mapped the experience. The conclusion was clear: No more dating advice. It can’t end well.

“Chemistry made me more logical and rational,” he said. “It comes easily to me, this way of thinking.”

His parents, Fermín and Miriam, do what they can to further the ambitions of the teenager they refer to as “the family intellectual.” But they’ve faced hardship, and Andrés has suffered the setbacks too. Four years ago, the family’s food distribution business in Tijuana went broke. Andrés had to quit school. Penniless, the family left the town where they’d lived for 19 years, with nowhere to go. An uncle who is a Jesuit priest arranged for them to settle on the plot of land in Puente Viejo, which is owned by the order.

After a rocky start, Fermín and Miriam became successful farmers, growing oats and corn, breeding pigs and cattle, and selling the eggs of their 200 chickens in city markets. Andrés won his scholarship and turned his focus to school. On Wednesday afternoons, he puzzles over tricky equations at the Chemistry Club, which he helped set up. Fridays are for debates at the student literary magazine. Summers he works, but last year he also pored over college chemistry textbooks — and came in second at the regional chemistry Olympics.

His parents congratulated him on the win, but just with words, Andrés said, not the hug he expected.

“It’s just my obligation, getting good grades,” he said with a shrug.

Andrés understands. His parents support him, but they know their son’s studies distance him from the family. It’s not just the long days he’s gone, which often extend into the weekends, or the distance to the big city. Their son often talks of the places he wants to go as a chemist — to college, to labs elsewhere, outside Mexico perhaps. Far from them.

Now the family are facing upheaval again.

More: The economic factors that keep young people from outdoing their parents.

The Jesuits asked them to find another place to live. They are starting over in the neighboring town of Juanacatlán, in the state of Jalisco. This time, Andrés is in his last year of prep school, and old enough to live without his parents.

To move with them or strike out on his own — it was a hard decision. But Andrés, so close to graduating, opted to stay. He wanted to finish school and go to college. So as his parents packed, he made arrangements for his own move. He’d stay with friends in Guadalajara and finish the year.

Andrés also wants to put a little more time into his second goal — winning over that beautiful wife. So far, he hasn’t had time for a relationship. Living in Guadalajara would help. He’s signed up for Friday night salsa classes in the hopes they’ll shake off his shyness and put him at ease in parties. He’s already at ease with science.

—

Gonzalez is a journalist based in Mexico

Urban Transportation

Guadalajara, like most major cities in the developing world, struggles with congested roads and gaps in public transportation that make it difficult for people to get to places of work, study and play. This can limit educational and employment prospects for young people like Andrés, who live in underserved neighborhoods. Integrated public transportation systems, in which citizens have seamless access to a network of travel options, are less polluting, safer, and better for the economy. Today, one-third of trips in Guadalajara are on public transportation; private cars and non-motorized options like walking and biking make up another third each. But the number of private cars on the road has been going up, from 1.6 to 1.8 million vehicles between 2007 and 2015. This is not a long-term solution. In fact, it makes existing problems worse. Improving the quality and reach of public transportation should be the priority instead.

—Harvey Scorcia, urban transport specialist and principal executive with the Development Bank of Latin America (CAF)

Economic Instability

In many ways Andrés is fortunate: He won a scholarship to a prep school and has friends he can stay with while he completes his studies. But his situation shows how family circumstances can make it harder for kids to achieve their full potential. Factors outside a young person’s control, including parental education, income and place of residence, are strong determinants of a student’s ability to pursue an education. Latin America and the Caribbean made huge strides in expanding access to basic services, including education, between 2000 and 2014, according a 2016 World Bank report. But that access remains unequal. Continued improvement in educational opportunities for young people like Andrés will be key to the region’s success if it hopes to maintain the economic and social growth that have marked last decade.

—Conor Bohan, founder and executive director of the Haitian Education and Leadership Program