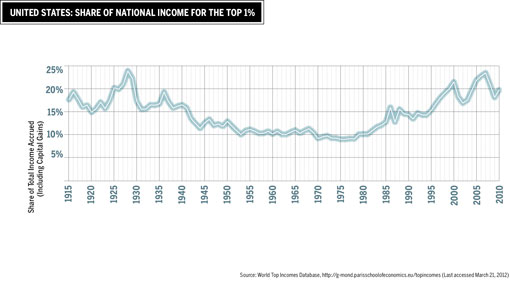

What is the income share of the region’s super-rich? It may be hard to believe, but this question can be answered only for Canada and the United States. Thanks to the tax transparency of these two countries and the herculean work undertaken by the Top Incomes Project, we know the share of income received by the richest individuals since 1913 in the U.S. and since 1920 in Canada.1 The top 1 percent’s share of national earnings in the U.S. can be seen in the graph on the next page.

Unfortunately, for Latin America and the Caribbean no such information exists.

Much has been said about the good news of declining inequality in the region.2 Yet the information we use for all these analyses comes from household surveys. The problem is that the surveys do not include information on rich households.

How do we know? Just look at the income of the richest households in any survey in any country. For example, the 2006 household surveys in Argentina, Brazil, Mexico, and Peru report that the average monthly incomes of those countries’ two richest households were equal to $14,000, $70,000, $43,000, and $17,500 dollars, respectively.

Compare this to Merrill Lynch estimates that in Latin America there are approximately 4,400 ultra-high-net-worth individuals, each with assets of at least $30 million. Assuming these individuals on average earn a return of 5 percent per year, they are potentially earning $2 million per month.

Something’s not getting reported.

So, what needs to be done to know the income shares of the rich in Latin America? The answer is simple. Governments should publish the information from tax returns (without identifying anyone by name, of course)—the same way that all Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) member countries have been doing for decades, except for OECD members Chile, Mexico and Turkey.

Shouldn’t the citizens of the region be allowed to know how their national income is distributed? Aren’t citizens and legislators entitled to know how much each income class contributes (or should contribute) in taxes? Shouldn’t governments be held accountable to their commitment to transparency in information systems?

As long as information on incomes and taxes paid is kept from the public, genuine discussion on tax reforms will be impossible. If we do not know who bears the tax burden today, how can we judge the impact of any proposed tax reform?

Our goal should be to be able to do what the Washington DC-based Tax Policy Center is able to do: any time Congress or a presidential candidate presents a proposal, the center estimates who benefits and who loses. But to get there, governments in Latin America need to release their tax information. And since it would be revealed anonymously—as it is done in the OECD-member countries mentioned—there should be no concerns about revealing the identities of the very rich.

The only excuse, really, is a desire to keep things less than transparent. And that’s no excuse.

ENDNOTES:

1. http://g-mond.parisschoolofeconomics.eu/topincomes/

2. Nora Lustig, “The Decline in Inequality in Latin America: Policies, Politics or Luck?,” Americas Quarterly 5(4) (2011):43-46.